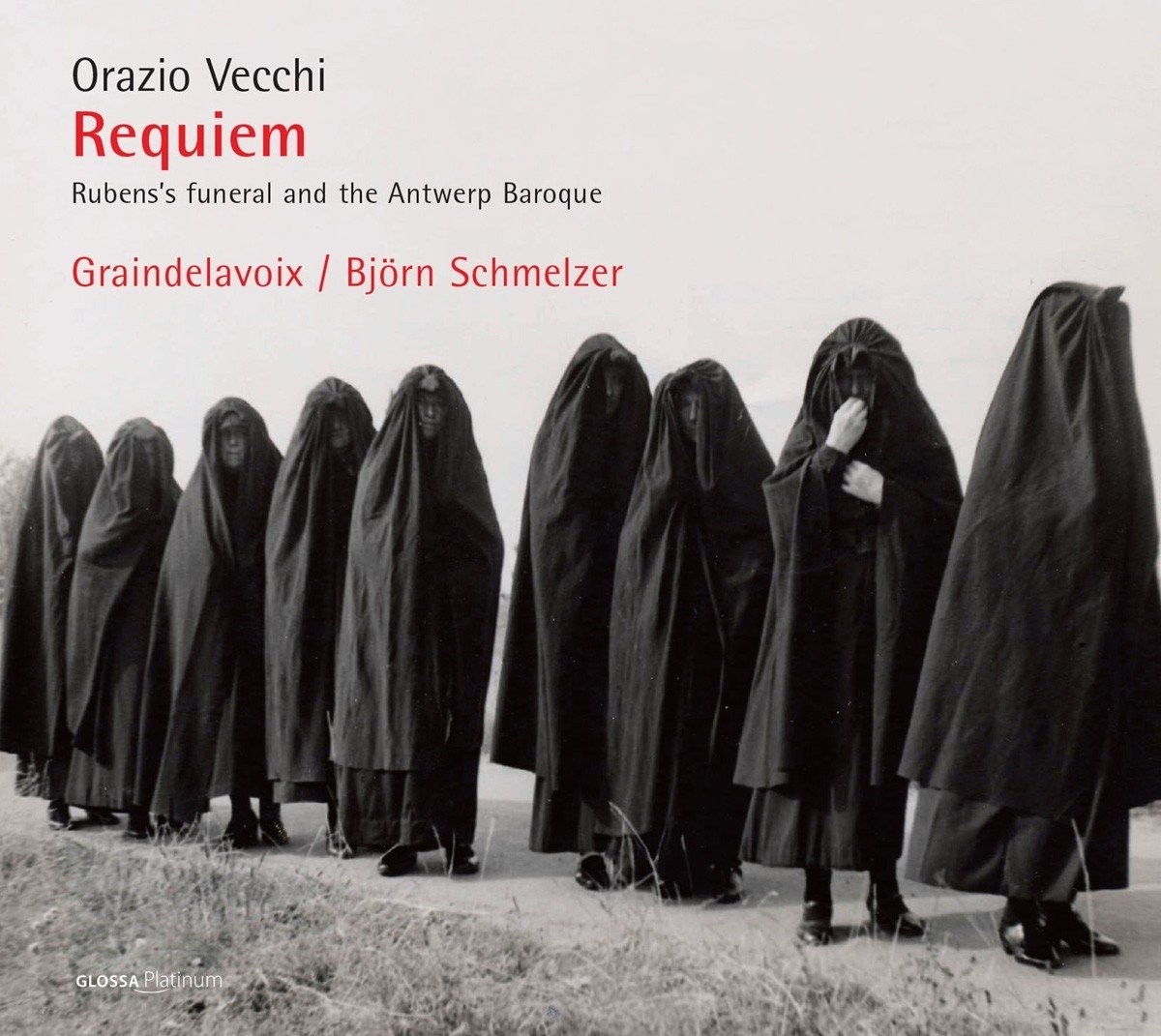

The cover photograph immediately strikes a discordant note, a jolt of anachronistic surprise. It initially evokes images of Mediterranean pleureuses, professional mourners steeped in lament, yet it unveils a funeral procession from the quaint island of Wieringen in North Holland. This arresting visual serves as the gateway to Paolo Bravusi’s Missae senis et octonis vocibus – Libera me Domine, performed by GRAINDELAVOIX, a recording that prompts a re-evaluation of Baroque conventions, particularly when considering figures like Peter Paul Rubens alongside the innovative musical interpretations of Bjorn Schmelzer.

Initially, Bjorn Schmelzer’s rendition of Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame left me skeptical. His approach seemed eccentric, an impression reinforced by his accompanying booklet essay. However, further listening, complemented by a detailed discussion with Schmelzer himself, led to a softening of my initial judgment. This journey of reconsideration prompted an exploration of his discography, encompassing twelve recordings released over the past decade. It’s through this body of work that Schmelzer, alongside the ensemble Graindelavoix, challenges preconceived notions of early music performance.

Graindelavoix, established in 1999, began its recording journey with Glossa Classical in 2006. More than a conventional early music ensemble, Graindelavoix functions as an artistic collective, a space for experimentation across performance and creation, guided by Bjorn Schmelzer. Their name, drawing inspiration from Roland Barthes’ essay on the “grain of the voice,” reflects their core pursuit: to explore the visceral essence of voice, the tangible and spiritual resonance within it. This exploration seeks to uncover the profound expressiveness residing within the very texture of vocal performance.

Schmelzer’s recordings are characterized by narrative concepts, weaving intricate webs of associations between diverse periods, styles, and genres. His latest project delves into the contrast between prima prattica polyphony, reminiscent of earlier musical eras, and the dynamic Baroque painting style epitomized by Peter Paul Rubens. Schmelzer posits that the music on this recording might have been performed at Rubens’s funeral. He suggests, “The deceased person inside the coffin was no less than the most famous of all Baroque painters, Peter Paul Rubens, and it is highly plausible that the Requiem Mass performed by the cathedral choir at this solemn occasion was an eight-part work including a polyphonic Dies irae, printed in Antwerp 28 years prior, composed by the Italian, Orazio Vecchi.” This hypothesis anchors the recording in a specific historical and artistic context, linking the auditory experience to the visual grandeur of Rubens’s world.

However, the attribution of the Requiem to Orazio Vecchi is not without its complexities, prompting a deeper investigation into the musical history of the period.

The Vecchi Requiem

Vecchi Missa pro defunctis – Dies irae

The Online Grove Dictionary attributes a polyphonic Dies irae to Orfeo Vecchi. The Dies irae text, attributed to Thomas of Celano, is thought to have evolved from a rhymed trope of the responsory Libera me. Before the Council of Trent, polyphonic settings of Dies irae were uncommon, with Antoine Brumel’s Requiem being a notable exception. The Grove mentions settings by composers like Asola, Orfeo Vecchi, Anerio, and Pitoni within their requiem compositions. This context highlights the rarity and significance of polyphonic Dies irae settings during this period.

An earlier edition of Grove, however, credits Orazio Vecchi with a polyphonic Dies irae published in Antwerp in 1612. This discrepancy underscores the existing confusion between Orazio Vecchi (1550-1605) and Orfeo Vecchi (1551-1603), contemporaries with similar names but distinct career paths.

Orfeo Vecchi primarily focused on sacred music, while Orazio Vecchi gained fame for secular madrigals, culminating in L’Amfiparnaso (1597), a dramatic madrigal cycle foreshadowing Baroque opera. Intriguingly, the online Grove omits the earlier reference to Orazio and the 1612 publication, as well as the Missa pro defunctis attributed to Orazio Vecchi. Adding to the complexity, Orfeo Vecchi also composed a Missa pro defunctis in 1598, as did Lorenzo Vecchi (c.1564–1628). Despite the shared surname and musical inclinations, there is no apparent familial relationship between these composers, although Orfeo had a musically inclined brother.

Despite the attribution uncertainties, let’s proceed with Bjorn Schmelzer’s premise that Orazio Vecchi composed the Requiem on this recording. Several recent sources support the attribution of an eight-voice Missa pro defunctis to Orazio Vecchi. Ultimately, the precise attribution doesn’t diminish Schmelzer’s intended exploration of the Antwerp Baroque context.

Vechhi Missa pro defunctis – Kyrie

For his Glossa CD, Bjorn Schmelzer draws inspiration from the 1640 funeral rites of Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens. This historical event, potentially featuring Orazio Vecchi’s Requiem Mass, serves as a lens through which Schmelzer examines the coexistence of seemingly contradictory yet interconnected facets within Baroque Antwerp.

One facet is the enduring presence of prima prattica polyphony. Antwerp was a significant center for music printing, and Vecchi’s Requiem, alongside works by composers like George de La Hèle, Duarte Lobo, and Pedro Ruimonte (whose Agnus Dei pieces conclude the recording), were disseminated from this city. The other facet is the vibrant, energetic, and opulent imagery of Rubens’s art—the epitome of Northern Baroque. This juxtaposition forms the core of Schmelzer’s artistic concept.

Schmelzer observes, “As we listen to the music and contemplate Rubens’s paintings, a palpable sense of rupture or dissonance emerges. Something feels amiss, a challenge in aligning this music with the conventional image of the Baroque as embodied by the Antwerp painter.” This perceived disconnect invites a deeper exploration of the period’s complexities.

Part of this apparent contradiction stems from the terminological frameworks used by historians and musicologists. Music historians generally place the Renaissance era around 1400-1600, preceding the Baroque period. However, the Renaissance in other disciplines began roughly a century earlier. Vecchi composed his Requiem in 1597 (published 1612), within the Renaissance timeframe, while Rubens is unequivocally a Baroque painter. Schmelzer emphasizes that the date of composition is less significant than the evidence suggesting Vecchi’s Requiem remained relevant and performed well into the 17th century.

Duarte Lobo Missa Dum aurora – Agnes Dei

Schmelzer’s central hypothesis posits a dual nature of the Antwerp Baroque. “[Schmelzer’s] hypothesis is that the Baroque in Antwerp had two faces. The first is the face of Rubens and his colleagues: the victorious, grandiose, counter-Reformatory Baroque with its endless folds of matter and materials. The second is a more complex and relatively unknown expression of the Baroque, a face turned away, veiled in darkness, a Baroque in disguise. These two faces are not separate but are sides of the same coin.” This nuanced perspective encourages a re-evaluation of the Baroque beyond simplistic notions of grandeur and ornamentation.

Schmelzer’s hypothesis, in essence, contrasts Rubens’s sensual and dynamic paintings with Vecchi’s more austere polyphony. Regardless of one’s interpretation of Schmelzer’s approach, his recordings are undeniably captivating, offering both exceptional vocal performances and a fresh lens through which to experience early music. The interplay between Peter Paul Rubens’s visual world and Bjorn Schmelzer’s sonic interpretations creates a rich and thought-provoking artistic dialogue.

George de La Hèle Missa Praeter rerum seriem – Agnes Dei .

To purchase

References

[1] Björn Schmelzer, CD booklet, “Orazio Vecchi (1550-1605): Requiem.” Glossa GCD P32113.

[2] Glossa website, “Orazio Vecchi (1550-1605): Requiem – Rubens’s funeral and the Antwerp Baroque.” accessed March 16, 2017, http://www.glossamusic.com/glossa/reference.aspx?id=424.

[3] Ibid.

[4] John Caldwell and Malcolm Boyd. “Dies irae.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 16, 2017, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40040.

[5] Grove, George, and J. A. Fuller-Maitland. 1910. A dictionary of music and musicians. New York: Macmillan, p. 700.

[6] Chase, Robert. 2006. Dies irae: a guide to requiem music. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

[7] Glossa website, “Orazio Vecchi (1550-1605): Requiem – Rubens’s funeral and the Antwerp Baroque.” accessed March 24, 2017, http://www.glossamusic.com/glossa/reference.aspx?id=424.

[8] Björn Schmelzer, CD booklet, “Orazio Vecchi (1550-1605): Requiem.” Glossa GCD P32113.

[9] Ibid.