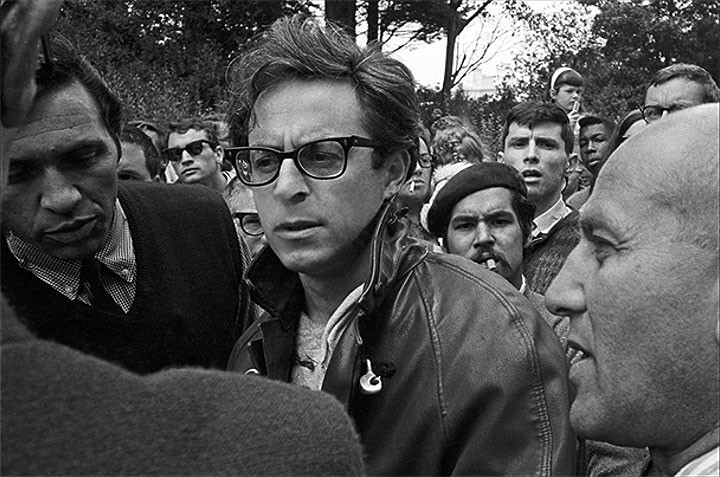

Peter Berg (1937-2011) was a multifaceted figure, renowned as a playwright, dramaturge, anarchist tactician, and, perhaps most notably, a pioneering bioregionalist. While his name might not be universally recognized, Berg was a central figure in the San Francisco counterculture of the 1960s, co-founding the radical performance group, the Diggers. His life and work embody a profound commitment to social change, environmental consciousness, and community empowerment. This exploration delves into the life and ideas of Peter Berg, revealing the man behind the myth and his enduring influence on contemporary thought and activism.

Berg’s journey began in 1937, a year that coincided with another numerically significant anniversary, mirroring the cyclical nature of attention he would later experience regarding the Summer of Love. His upbringing, as he described it, was steeped in a form of “immigrant folk socialism.” His mother identified as a “parlor pink,” and his father, while a self-proclaimed “barroom socialist,” instilled in him an awareness of social and political currents. This early exposure to leftist ideologies, albeit tempered by his father’s complex character, likely laid the groundwork for Berg’s later radicalism. Even his brothers’ enlistment in World War II, framed as the “War Against Fascism,” reflected the prevailing political language of the era, a blend of FDR’s New Deal liberalism and socialist ideals.

He initially pursued higher education at the University of Florida, driven more by the desire to experience college life than a specific academic calling. Choosing psychology as a major almost arbitrarily, Berg’s true intellectual engagement was found outside the classroom, in the world of literature. He immersed himself in novels, absorbing the American ethos and igniting a desire to explore its diverse landscapes and cultural expressions. This literary exploration fueled hitchhiking journeys across the country, including a formative trip to San Francisco, a city already resonating with countercultural stirrings.

San Francisco, for Berg, was a destination shaped by literature, specifically Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl.” Reading “Howl” the night Fidel Castro took Havana cemented in his mind San Francisco as a hub of artistic and social revolution. His early experiences in the city included a brief foray into factory work, experiments with LSD, and a month-long sojourn in Mexico, experiences that collectively contributed to a period of “reverse culture shock” upon returning to the materialistic environment of California.

This period of introspection and cultural dissonance led Berg to an unexpected creative outlet: the San Francisco Mime Troupe. In the mid-1960s, he walked into the Mime Troupe, boldly declaring himself a writer, director, and actor. R.G. Davis, the Troupe’s adventurous director, recognized Berg’s raw talent and handed him a challenging project: adapting Giordano Bruno’s unplayable philosophical play Il Candelaio into a three-act Commedia dell’arte. This marked Berg’s entry into the world of theater and his first collaboration with Luis Valdez, who later founded El Teatro Campesino.

The Mime Troupe, at this time, was not just a theater group; it was a hotbed of radical thought and action. A pivotal moment occurred when the city of San Francisco withheld funding, leading the Troupe to stage a play in the park without a permit, fully anticipating arrest. This orchestrated “bust” became a galvanizing event, uniting various countercultural factions – old Communists, Beats, gays, proto-hippies, musicians, and the underground press – into a nascent “New Left.” The arrest, while staged, had a profound real-world impact, solidifying a sense of shared identity and purpose among these disparate groups.

The aftermath of the arrest saw benefits organized for the financially strapped Mime Troupe, managed by a young Bill Graham. This event, with its eclectic mix of performers including Frank Zappa, Timothy Leary, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, became a landmark, signaling the emergence of a broader counterculture. Berg and his fellow dramaturges recognized the significance of this moment, analyzing it through the lenses of Antonin Artaud and Bertolt Brecht, seeking to understand how to break down the “fourth wall” and engage the audience directly in theatrical events.

From this crucible of experimentation, Berg coined the term “guerrilla theater.” Unlike traditional theater confined to stages, guerrilla theater sought to blur the lines between performance and reality, using public spaces as stages and involving unsuspecting audiences in theatricalized events. Berg’s vision extended beyond mere provocation; he saw guerrilla theater as a tool for social transformation, capable of staging events that brought the audience onto the stage, even when there was no formal stage.

One of the earliest and most impactful examples of Berg’s guerrilla theater was “Centerman.” Inspired by Wolfgang Borchert’s short story “The Dandelion,” the play depicted the brutal treatment of prisoners of war. However, instead of staging it in a traditional theater, Berg and the Mime Troupe took “Centerman” to the Free Speech Movement (FSM) protests at UC Berkeley. Without announcement, actors in prisoner fatigues and a guard began performing amidst the crowd of students. The performance, deliberately ambiguous and shocking, blurred the line between theater and reality, leaving onlookers questioning whether they were witnessing a real event or a performance. The play culminated in the staged murder of a prisoner, eliciting strong emotional reactions from the unsuspecting audience.

“Centerman” at Berkeley was a watershed moment, solidifying the concept of guerrilla theater and demonstrating its power to provoke, engage, and unsettle audiences. It marked a radical departure from traditional theater, embracing spontaneity, improvisation, and direct confrontation with social and political realities. Following this success, Berg and the Mime Troupe continued to experiment with guerrilla theater, staging performances in bus stations and rock clubs, further blurring the boundaries between art and life.

Another notable guerrilla theater piece was “Search and Seizure,” performed at the Matrix, a rock club, alongside Country Joe and the Fish. The play depicted a narcotics raid, with actors portraying drug users being interrogated by undercover officers. The performance was so realistic that audience members, including Country Joe himself, believed it to be real, highlighting the immersive and unsettling nature of guerrilla theater. Emmett Grogan, a charismatic and enigmatic figure who would later become a central Digger, played a role in “Search and Seizure,” showcasing his talent for “life acting” – blurring the lines between performance and lived experience.

Berg also explored themes of technology and societal control in “Output You,” a guerrilla theater piece that predated widespread public awareness of computers. “Output You” depicted computer programmers and their “doubles,” exploring the dehumanizing potential of cybernetic culture and the suppression of human emotion in a technologically driven society. These early explorations into technology and its social impact foreshadowed Berg’s later bioregionalist concerns with ecological balance and human connection to nature.

The concept of the Diggers emerged from this fertile ground of guerrilla theater and countercultural experimentation. Billy Murcott, another key figure in the early Diggers, coined the name, drawing inspiration from the 17th-century English Diggers and the contemporary slang term “dig.” Murcott and Grogan, witnessing the Fillmore riots in 1966, envisioned the Diggers as a white equivalent to the black rebellion, a movement that would challenge societal norms and embrace radical freedom.

The Diggers, initially envisioned by Murcott and Grogan, took shape with Berg’s guidance and theatrical sensibilities. Berg saw the Diggers as an extension of guerrilla theater, taking performance from the stage to the streets of Haight-Ashbury. The Diggers aimed to create “street theater where the street is the theater,” transforming the Haight-Ashbury into a stage for social change.

Inspired by Luis Valdez’s Teatro Campesino and its integration of theater with social action during the Delano grape strike, Berg envisioned the Diggers as enacting the society they wished to create. He opened the “Free Store,” named “Trip Without a Ticket,” embodying the Digger credo: “Everything is free. Do your own thing.” This free store became a physical manifestation of anarchist principles, a space where goods and services were freely shared, challenging capitalist notions of ownership and exchange.

The Diggers’ philosophy extended beyond the Free Store, encompassing a range of “free” initiatives – free food, free housing, free energy, free art. The tie-dye craze, a defining visual element of the hippie movement, originated in the Digger Free Store. Luna, a woman involved with the Diggers, introduced tie-dye techniques, transforming surplus white shirts into vibrant works of wearable art, exemplifying the Digger principle of free art and resourcefulness.

However, for Berg, the “highest form of free art” were the Digger street events. These events, often pageant-like in scale and theatricality, blurred the lines between performance and reality, immersing unsuspecting audiences in orchestrated situations designed to challenge perceptions and provoke social change.

The Diggers’ free food program, serving meals in Golden Gate Park, became a defining symbol of their ethos. For Berg, free food was not just about feeding the hungry; it was a “demonstration of an attitude – that food should be free.” It was a practical enactment of a desired future world, a “guiding ideal” that challenged the capitalist notion of food as a commodity.

The Diggers’ free food service was not merely functional; it was imbued with theatricality and symbolism. Food was served within a 12-foot square orange frame, dubbed the “Free Frame of Reference,” aimed at morning commuters, transforming the act of receiving free breakfast into a deliberate “painting,” a visual statement challenging societal norms.

The Diggers extended their theatrical approach to all aspects of their activities. At the Free Store, they orchestrated situations designed to provoke thought and challenge conventional interactions, blurring the lines between reality and performance. The Free Store itself became a stage for social experimentation, revealing both the utopian aspirations and the practical challenges of a gift economy.

Berg’s theatrical perspective permeated his understanding of Digger actions. He viewed their activities as “life acting,” creating conditions that reflected their desired social reality. Drawing inspiration from Theodor Gaster’s Thespis, Berg saw the Diggers as enacting a ritual pageant, similar to the Pharaoh’s Nile journey, creating the very condition they were describing – a free and liberated society.

One of the most ambitious Digger street events was “The Birth of Haight and the Death of Money.” This large-scale spectacle transformed Haight Street into a living theater, involving thousands of participants in a series of orchestrated events designed to symbolize the rejection of materialism and the birth of a new, free culture. The event featured symbolic characters, like animal-headed figures carrying a coffin of money, rooftop performances, and waves of distributed objects like penny whistles and mirrors, creating a multi-sensory, immersive experience.

“The Birth of Haight and the Death of Money” exemplified the Digger approach to street events – a blend of theatricality, symbolism, and spontaneous participation, creating a collective experience that challenged societal norms and celebrated countercultural values. The event was meticulously planned yet allowed for improvisation and audience participation, blurring the lines between performers and spectators.

The Diggers’ emergence coincided with a shift in San Francisco’s cultural landscape, with the creative energy moving from North Beach to Haight-Ashbury. Beat poets and artists, initially critical of mainstream society, saw in the psychedelic rebellion and the Diggers a realization of their own desires for social and cultural transformation. Figures like Lenore Kandel, Richard Brautigan, and Allen Ginsberg embraced the Diggers, seeing them as the “children of their desires,” the proactive manifestation of Beat protest.

LSD played a crucial role in the emergence of the Diggers and the broader counterculture. Berg believed that “the psychedelic rebellion would not have happened without LSD.” LSD, as a “consciousness-changing agent,” provided the “magical ingredient” that empowered individuals to challenge societal norms and envision alternative realities. Berg saw the Diggers themselves as “social LSD,” a force that could “turn reality upside down AND BE BEAUTIFUL.”

While not explicitly missionaries for LSD, the Diggers facilitated its distribution and integration into the counterculture. At the Human Be-In, a pivotal event in the Summer of Love, the Diggers distributed 3,000 tabs of LSD, provided by Owsley Stanley, contributing to the event’s psychedelic atmosphere and its symbolic significance.

Communication was central to the Diggers’ activities. They utilized broadsheets produced by the Communications Company (Comm/Co), founded by Chester Anderson and Claude Hayward. Comm/Co’s broadsheets served as a vital communication tool, disseminating information about Digger events, social services, poems, and political statements. Chester Anderson, a Beat-era figure in rebellion against his military background, provided the technological means for the Diggers to communicate their message widely.

The Diggers’ relationship with the Grateful Dead was complex and evolving. Initially, the Grateful Dead were hesitant to engage with the Diggers’ free events. However, Danny Rifkin, the band’s road manager, recognized the potential for the Grateful Dead to connect with a wider audience through free performances in Golden Gate Park. The Grateful Dead’s participation in Digger events, facilitated by Rifkin’s vision and the Diggers’ invitation, became a defining moment, solidifying their association with the counterculture and expanding their fanbase.

The Diggers also organized indoor events, such as the Free City Convention, held at the Carousel Ballroom, featuring Janis Joplin, Stanley Mouse, and a diverse cross-section of San Francisco society. These events further blurred the lines between performance, social gathering, and political statement, embodying the Digger ethos of free expression and community building.

One of the most audacious and chaotic Digger events was the Invisible Circus, held at Glide Memorial Church. Organized in collaboration with the Artists Liberation Front, the Invisible Circus was a 72-hour immersive experience that transformed the church into a living, breathing artwork, challenging societal norms and pushing boundaries of artistic and social expression.

The Invisible Circus encompassed a wide range of performances, installations, and participatory events, reflecting Berg’s desire to “turn around every pet annoyance” he had with society. From belly dancers crashing through newsprint walls to an “obscenity panel” juxtaposed with a live nude performer, the Invisible Circus was designed to shock, provoke, and liberate. Lenore Kandel played a key role in convincing Glide Church to host the event, arguing for its spiritual and liberatory purpose.

The Invisible Circus featured contributions from numerous artists and countercultural figures, including Richard Brautigan, Emmett Grogan, and Mike McClure. Brautigan’s “John Dillinger Computer” provided instant poetry publishing, while Grogan filled an elevator with shredded plastic, creating a surreal and disorienting experience. The event attracted a diverse audience, including Hells Angels, military personnel, and members of the Tenderloin’s homeless population, creating a chaotic and transformative social space.

The Invisible Circus, while ultimately shut down by church authorities after 36 hours due to its chaotic and boundary-pushing nature, became a legendary event, embodying the Digger spirit of radical experimentation and social liberation. Cecil Williams, the newly appointed pastor of Glide Church, while not directly involved in the Invisible Circus, inherited a church that had been profoundly impacted by the event, setting the stage for Glide’s future role as a progressive and community-oriented institution.

Berg and the Diggers also engaged with national political movements, attending a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) conference in Michigan in 1966. Berg, along with Emmett Grogan, Billy Murcott, and Bill Fritsch, traveled to the SDS conference with the intention of presenting the Digger ethos as a model for radical social change.

The Digger delegation’s arrival at the SDS conference was characteristically chaotic, marked by a car accident and Bill Fritsch’s subsequent arrest. Despite the mishaps, Berg seized the opportunity to address the SDS gathering, advocating for a shift from traditional political activism to a more performative and experiential approach, urging SDS to “become Diggers.” Abbie Hoffman, present at the conference, was inspired by the Digger presentation, foreshadowing his own embrace of theatrical activism and the formation of the Yippies.

The Digger delegation’s encounter with SDS was emblematic of the broader tensions within the New Left, between traditional political organizing and more countercultural, performative forms of activism. While SDS, in Berg’s view, was “ready to fall,” the Diggers offered a different path, one that emphasized direct action, cultural transformation, and the blurring of art and life.

Following the SDS conference, the Diggers expanded their reach, establishing connections with East Coast counterparts, including the New York Diggers, led by Martin Carey, Susan Carey, and Abbie Hoffman. The New York Diggers replicated many of the San Francisco Diggers’ initiatives, including free stores and street events, demonstrating the broader appeal and adaptability of the Digger model.

Berg himself engaged with mainstream media, appearing on The Alan Burke Show, a confrontational television program known for its aggressive host. Berg used the platform to subvert Burke’s format, directly addressing the audience and staging a theatrical exit, complete with a pie-in-the-face incident and a symbolic deconstruction of the television studio itself. This performance on The Alan Burke Show exemplified Berg’s media savvy and his ability to turn even hostile environments into opportunities for guerrilla theater and countercultural messaging.

The Diggers’ relationship with the Hells Angels was another complex and multifaceted aspect of their history. While some Digger women had romantic relationships with Hells Angels, Berg’s perspective was more strategic, seeing the Hells Angels as a necessary “heavy” element in the counterculture, capable of confronting authority and protecting the Diggers’ free spaces.

Berg recognized that the police, ultimately, were the force that “closed down the Haight-Ashbury.” Despite euphemisms about hard drugs or the fading of the Summer of Love, Berg argued that the police militarization of Haight Street, with increased patrols, harsh lighting, and traffic restrictions, was the primary cause of the neighborhood’s transformation and the decline of the counterculture’s utopian experiment.

The Diggers’ slogan, “1% Free,” was deliberately provocative and ambiguous. For Berg, it meant that “only one percent of the population can bring this off, at this time.” It was an aspirational statement, challenging the rest of society to join the Diggers in their pursuit of freedom and social transformation, aiming to expand that “one percent” until it became “a hundred percent.”

The “1% Free” slogan also reflected the Diggers’ understanding of their own position within society – a radical minority challenging the status quo. The slogan, often displayed alongside an image of Chinese Tong members, sparked dialogue and misinterpretations, with some Haight Street merchants mistakenly believing it was a form of extortion.

Peter Berg’s legacy extends far beyond the San Francisco Diggers and the 1960s counterculture. In 1973, with his wife Judy Goldhaft, Berg co-founded Planet Drum Foundation, a bioregionalist non-profit organization that continues to this day. Planet Drum became the primary vehicle for Berg’s bioregionalist vision, advocating for ecological awareness, community self-reliance, and a deep connection to place. Bioregionalism, as articulated by Berg, is a philosophy and a practice that emphasizes living within the ecological and cultural boundaries of a specific bioregion, fostering local self-sufficiency, ecological restoration, and a sense of place-based identity.

Berg’s work in bioregionalism was a natural extension of his Digger ethos, shifting the focus from social revolution to ecological and cultural regeneration. Planet Drum’s work, encompassing publications, workshops, and community projects, has had a lasting impact on the bioregional movement and the broader environmental movement. Peter Berg, the former guerrilla theater artist and Digger, became a leading voice in bioregionalism, advocating for a radical shift in human consciousness and a more harmonious relationship with the planet.

Peter Berg’s life and work offer a compelling example of the interconnectedness of social activism, artistic expression, and environmental consciousness. From his early experiments with guerrilla theater to his pioneering work in bioregionalism, Berg consistently challenged conventional boundaries and sought to create a more just, sustainable, and liberated world. While “Who Is Peter Berg” might not be a household query, understanding his contributions unveils a significant thread in the tapestry of countercultural history and its ongoing relevance to contemporary challenges. His legacy as a visionary architect of both social and ecological change continues to inspire and provoke, reminding us of the transformative power of art, activism, and a deep commitment to creating a better world.