I have this theory about Indians. Actually, the theory is not really about Indians, it’s about everyone else. Here’s the thing: although I don’t mean to hurt anyone’s feelings, generally speaking white people who are interested in Indians are not very bright. Generally speaking white people who take an active interest in Indians, who travel to visit Indians and study Indians are even more not very bright. I further theorize that, generally speaking, smart white people realize early on that the whole Indian thing is an exhausting, dangerous, and complicated snake pit of lies. And without it ever quite being a conscious thought, these intelligent white people come to acknowledge that everything they are likely to learn about Indians in school, from books and movies and television is probably going to be crap.

Paul Chaat Smith, Everything You Know About Indians is Wrong (2009)

As someone who, like many, has been captivated by the narrative of Native American culture, Paul Chaat Smith’s provocative words resonated deeply. While the term “Indian,” particularly in the context of “Peter Pan Indians,” can be loaded and even offensive, it remains a term historically used and understood, especially when discussing older representations. It’s important to acknowledge that many Indigenous peoples in the US today use collective names such as Native American, First Nations, First Peoples, Indigenous, and Alaska Native. Smith, a Comanche artist and museum curator, urged a critical look at the pervasive imagery of “Indians” in popular culture, specifically those “Peter Pan Indians” that entered the collective consciousness through J.M. Barrie’s works and Disney’s adaptations.

Born in the 1950s in the US, like many children, my first encounter with Native peoples was through Disney’s 1953 animated film, Peter Pan. This film, along with the Broadway musical adaptation of 1954, solidified deeply ingrained stereotypes about Native Americans. Disney’s portrayal of “Peter Pan Indians” sadly echoed offensive team mascots, depicting them speaking broken English and behaving foolishly. The accompanying music was equally problematic, filled with crude imitations of Native speech and relying on musical tropes of primitivism, most notably the stereotypical “Indian beat”: Dum–dum-dum-dum. The Broadway musical, further popularized by the 1960 NBC live broadcast and subsequent adaptations available on platforms like YouTube, continued this patronizing representation. Costumes, makeup, wigs, and choreography all contributed to a caricature of “braves.” Tiger Lily’s song, “Ugg-A-Wugg,” set to the ubiquitous “Indian beat,” further infantilized her character. Essentially, everything Peter Pan presented about “Indians” was, in Smith’s words, “crap.” Yet, this film and musical remain cherished cultural artifacts, shaping generations of non-Natives to view Indigenous peoples through a distorted lens.

This problematic portrayal occurred during a particularly damaging period for Native Americans in the US. Coinciding with the release of Disney’s Peter Pan, the US Congress implemented policies aimed at terminating Indian tribes and forcibly relocating Native peoples from reservations to urban centers, furthering assimilation and cultural genocide. While no direct link exists between the Disney film and federal policy, the film undeniably reflected the socio-political climate of North America at the time. Today, the loss of language and cultural heritage resulting from these assimilation policies remains a critical concern for Native American communities. Significant efforts are now directed towards cultural revitalization and reclamation. Academic institutions advocate for “unsettling colonialism,” challenging settler-colonial frameworks through critical analysis and activism. But can we truly unsettle deeply embedded cultural icons like Peter Pan? This article focuses on the responses of three contemporary Indigenous artists—Frank Waln (Sicangu Lakota), Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (Chickasaw), and Natanya Pulley (Diné)—who are actively reshaping settler perspectives on “Peter Pan Indians” through their art, offering powerful catharsis and fostering understanding.

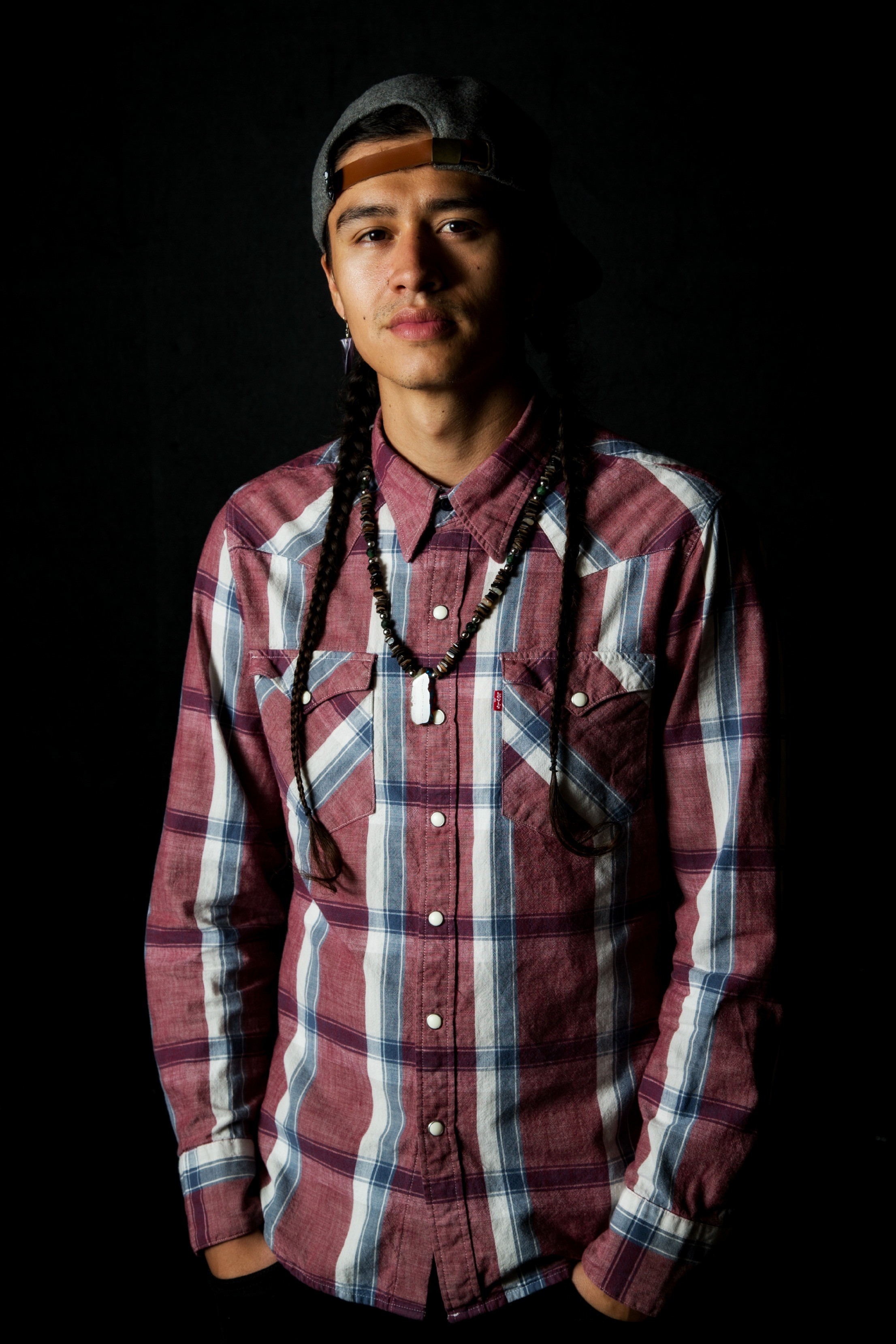

Artist Frank Waln (Sicangu Lakota), whose rap performance subverts a song from the 1953 animated Disney film Peter Pan. Credit Kernit Grimshaw Photography.

Frank Waln is a multifaceted artist – a musician, songwriter, performer, and producer. Like many Native American and First Nations artists, Waln finds a powerful connection with hip-hop, recognizing shared experiences of racism and oppression with African Americans. In a 2019 interview with the American Writers Museum, Waln articulated the power of storytelling: “Powerful storytelling can create pathways of empathy and understanding across cultural, racial and socioeconomic divides that were built up to keep us separated from one another. Most Indigenous nations have strong histories and traditions of storytelling so I see my art as a continuation of that tradition.”

Waln’s potent 2015 rap performance directly confronts and subverts the Disney song, “What Made the Red Man Red”. In a captivating performance at Café Cultura in Denver, Colorado, Waln powerfully reclaims the “Indian beat,” striking his chest to punctuate the rhythm in his remix. The stage lighting shifts through red, blue, green, and white, colors imbued with symbolic meaning in Lakota spirituality, transforming the venue into a Native space. Waln’s attire and personal style further assert his identity as a contemporary Native person, comfortable navigating diverse spaces, from ancestral homelands to reservations and urban environments. He presents himself authentically, wearing a t-shirt with a Native logo, a Native necklace, jeans, disc earrings, a baseball cap, and his long hair in a braid. His performance is dynamic, incorporating dance and direct audience engagement, inviting them to clap along. He strategically interjects ad-libs, adding layers of meaning. As the remix incorporates the offensive terms “pale face” and “savages” in the second verse, Waln echoes these words before rapping “savage is as savage does,” powerfully redirecting the accusation. After the line “all we get is a god damn mascot,” he ad-libs “I’m not your Redskin,” directly challenging the racist mascotry of the Washington Football Team, which has since changed its name. His lyrics, accessible online, showcase his masterful use of language, rhyme, and rhythm, directly refuting the broken English stereotype perpetuated by Disney’s “Indians.” While Disney has now added parental warnings to Peter Pan acknowledging its racist content and, in 2021, blocked it for children under seven on their streaming service, it remains widely available, underscoring the importance of Waln’s artistic intervention.

Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (Chickasaw), musical consultant to the 2014 live broadcast of Peter Pan. Photograph by Shevaun Williams.

When NBC revived a live broadcast of Broadway’s Peter Pan in 2014, they enlisted Jerod Tate as a musical consultant, specifically to “salvage” (Tate’s word) Tiger Lily’s problematic “Ugg-A-Wugg” song. Tate, a celebrated classical music composer who founded the Chickasaw Music Festival and co-founded the Chickasaw Summer Arts Academy, is a strong advocate for Native classical musicians. In a 2014 interview with Indian Country Today, Tate detailed his collaboration with the show’s musical director, David Chase, to address three key issues within the song. First, they revised the opening rhythm to emphasize the second beat, aiming for a sound closer to a Haudenosaunee Smoke Dance, referencing Barrie’s inspiration from ethnographies of Northeastern US Native peoples. Second, they tackled what Tate termed the “Indian breakdown,” a melody that evoked the Florida State University “War Chant” and its associated “tomahawk chop” gesture. They replaced this with a more generic dance tune, which Tate considered “the best anyone could have done” within the constraints of the musical. Finally, they changed the song’s title from the nonsensical “Ugg-A-Wugg” to “True Blood Brothers.” Tate explained their linguistic approach: “since ‘Ugg-A-Wugg’ was the word that Tiger Lily and Peter agree on as their call for help, we decided to look at the Wyandot language for an actual word that still fit that rhythm and the music. . . . I went through the Wyandotte Nation in Oklahoma and . . . we came up with the word Owa,he, the Wyandot word for ‘come here’.” (Wyandot is an Iroquoian language spoken by Wendat [Huron] peoples, and the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe).

Driven by respect for the original musical’s creators, Tate and Chase aimed to preserve the core of the work while mitigating its most offensive elements. Tate acknowledged the inherent challenges, stating, “It’s important to remember that musical theater, as a genre, is based in stereotypes. There are a lot of musicals that have kind of funky numbers like that. I’m not looking to cover anything up; I was just trying to bring more integrity and authenticity to that particular song.” Rather than eliminating the song entirely, their collaborative revision offers a model for respectfully updating problematic musical theater standards. The 2014 NBC live broadcast of Peter Pan, including Tate’s revisions, is available on YouTube, and the soundtrack is accessible through Broadway Records.

A screenshot of Carsen Gray (Haida) as Tiger Lily in P.J. Hogan’s 2003 film Peter Pan.

A central issue with Tiger Lily in Peter Pan is her two-dimensional characterization. Barrie describes her as “the most beautiful of the Dusky Dianas . . . coquettish, cold and amorous by turns; there is not a brave who would not have the wayward thing to wife, but she staves off the altar with a hatchet.” From the outset, Barrie’s portrayal fetishizes Tiger Lily as a fierce, beautiful, and provocative “Indian princess.” In Barrie’s original play and novel, she is given minimal dialogue, and when she does speak, it is in broken English. Visual representations in theater and film have historically perpetuated denigrating images of Native women. However, P.J. Hogan’s 2003 film version of Peter Pan, directed by the acclaimed Australian writer and director, attempts to rehabilitate some of this offensive imagery. Carsen Gray (Haida), as Tiger Lily, is depicted wearing a modest buckskin dress and speaks her single line of dialogue in a Native language. Significantly, she has a blue handprint painted across her face. In 2019, the red or black handprint became a powerful symbol of the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people (MMIWG2S). While no explicit connection to the MMIWG2S movement is apparent in Hogan’s film, the blue handprint for many viewers evokes the silenced voices of Indigenous women.

Natanya Anne Pulley (Diné), author of Tiger Lily and the Impossible Neverland (in progress). Photograph by Gray Warrior.

Natanya Ann Pulley directly addresses this silencing by giving Tiger Lily a voice in “from Tiger Lily and the Impossible Neverland,” an excerpt from her novel-in-progress published in The Massachusetts Review (2020). Through creative fiction, Pulley constructs Tiger Lily’s autobiography, allowing the character to articulate her thoughts on naming, identity, place, relationships, language, and song. Pulley’s Tiger Lily reflects on her very name: “I began misnamed. Before the page turned maybe. Lilium lancifolium. Lilium tigrinum, a synonym. Born of Asian lands: China, Japan, Korea—and also the Russian Far East. I am named such because perhaps I did not care for boundaries at the time. . . . Or perhaps this is what I am told to be.” Pulley masterfully reveals the intertwined colonial and exoticizing perspectives prevalent in late-Victorian thought, uncovering complexities that Barrie likely never considered.

Tiger Lily further reflects on the confined space of Neverland: “There is within this Neverland, but under those wigwams and fires, a place in which we, the tribe, lay ourselves down. Coffinlike, except that we can flatten ourselves in. Like papers, like those lines on paper. The book closing, we live between the pages.” Pulley’s words highlight how Native peoples, often confined to outdated literary and ethnographic representations, continue to exist and resist long after the book is closed, challenging the damaging images these representations perpetuate. Barrie’s Tiger Lily, in her “Indian princess” attire, unfortunately continues to inspire problematic costumes at festivals and parties. Sterlin Harjo (Seminole) and the 1491s comedy group satirize these harmful impersonations in their sketch “I’m an Indian Too,” filmed at the 2011 Santa Fe Indian Market. In Pulley’s narrative, the strained relationship between Tiger Lily and Tinker Bell illuminates the divisions between Indigenous and white feminisms. Tiger Lily observes, “She and I are not the same. She can claim not to fly and claim the wings define her too, but no matter, she can remove and grow them back, which is mobility in itself. I’ve nothing to remove, yes. But I’ve nothing to grow back either.”

The excerpt concludes with Tiger Lily’s poignant reflection on language and song: “I can conjure a memory of us speaking a tongue separate from the rest of Neverland,” she states.“ And I can almost hear the inflections and guttural reverberations and I can almost feel my throat as having made these sounds—I could not for a thing in the world think of a single word we had that was our own. . . . Even our songs seemed to be that of only drums—someone’s tune empty of us—and . . . I couldn’t place where the drumsong was housed. Was it one of our hearts or the lands or like the village popping up each morning, was it also handed to us for the purpose of playing it back? Who even played them?” Pulley’s meditation on songs resonates deeply with scholars engaged in the complex ethics of Indigenous music repatriation. Since 1890, ethnographers have recorded vast archives of Native songs, now housed in institutions. The 1990 US Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) has prompted efforts to return Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, including these recordings. However, the repatriation process is often intricate and fraught with challenges, as detailed in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation (Gunderson, Lancefield, and Woods, eds., 2019). In cases where repatriation is not feasible, Pulley’s question, who even plays these songs, remains a critical point of reflection.

Waln, Tate, and Pulley offer powerful and diverse approaches to unsettling the colonial foundations of Peter Pan. Waln utilizes rap and performance to subvert Disney’s song, transforming it into a potent expression of protest. Tate, through collaboration, navigates the complexities of musical theater stereotypes while striving to excise the most egregious elements of “Ugg-A-Wugg.” Pulley, through fiction, gives voice to Tiger Lily, empowering her to reclaim her narrative and humanity. These artists respond to Peter Pan from the lived realities of Indigenous peoples in an era of resurgence, confronting ongoing issues of racial profiling, treaty violations, sovereignty and land rights, intergenerational trauma, and social invisibility. Their art serves as a call for political protest and social justice, raising crucial awareness about the daily realities faced by Indigenous communities.

While engaging with Indigenous arts of resistance can be challenging for non-Natives, Paul Chaat Smith’s call to “engage, program, and critique Indian artists” is essential. He emphasizes that “the Indian experience is at the very center of how the world we live in today came to be.” The critical question is “whether we can build new understandings of what it means to be human in the twenty-first century. It isn’t about [Native people] talking and [non-Native people] listening. It’s about an engagement that moves our collective understanding forward . . . Good intentions aren’t enough; our circumstances require more critical thinking and less passion, guilt, and victimization.” While the impulse to simply relegate Peter Pan to archives might be tempting, engaging with it through the lens of Indigenous creators offers a vital opportunity for non-Natives to participate in decolonization, a crucial step towards reconciliation.

I want to thank Dr. Johann Buis and his students at McGill University for an insightful and inspiring discussion; Drs. Tamara Bentley, Lei X Ouyang, Natanya Pulley, and Melinda Russell for helpful feedback; Elizabeth Levine for technical assistance; and the editors of Musicology Now for patience and encouragement.

About the Sounds of Social Justice Roundtable

From Roundtable curator and Musicology Now editorial team member Joan Titus:

We have witnessed significant shifts in the past several years in terms of human and civil rights across the world, and within US politics. Music and sound are inevitably involved in the expressions of positions on these rights and the search for social justice. Pussy Riot’s songs and protests against discrimination, US Americans singing on the streets during protests, social media posts about identity and music by Indigenous Americans, and the revival of past music and civil rights icons, such as Nina Simone, in current popular media all point to civil unrest, and how music and sound are integral to human expression. This Roundtable, “Sounds of Social Justice,” offers a variety of perspectives from scholars and artists on music, sound, and social justice today. Each piece, published over the course of 2021-22, allows us to contemplate how people engage the global concept of social justice through specific cultures and media.

Listen to the previous contribution to this roundtable, “The Language of The Coding” a conversation between Neil Verma and Yvette Janine Jackson.