The visual landscape of Young Frankenstein is as much a character in the film as any of the actors, particularly Peter Boyle as the iconic Monster. The movie’s castle sets, brought to life by production designer Dale Hennesy, are not just backdrops; they are integral to the film’s atmosphere and comedic timing. Hennesy crafted an elaborate and almost fantastical castle complex, featuring courtyards, a grand reception hall, spiraling staircases, hidden passages, and bedrooms with secret panels, culminating in a laboratory equipped with a dramatic operating platform that ascends through the roof to an outdoor rooftop set, all under a perpetually stormy sky. This detailed construction, a true passion project for Hennesy, cost $400,000 and resulted in magnificent 35-foot-high sets, cobblestone streets, and intricately furnished rooms that were a cinematographer’s dream. Hennesy’s set decorations in varying shades of grey stone allowed for versatile tonal reproduction, manipulated by lighting and film processing techniques. His contribution was undeniably crucial to the overall visual aesthetic of the film.

The reception hall, a vast and elaborate creation by Dale Hennesy, served to emphasize the scale of the castle. Actors appeared small against the 35-foot walls, 15-foot doors, and a fireplace measuring 6 feet by 10 feet.

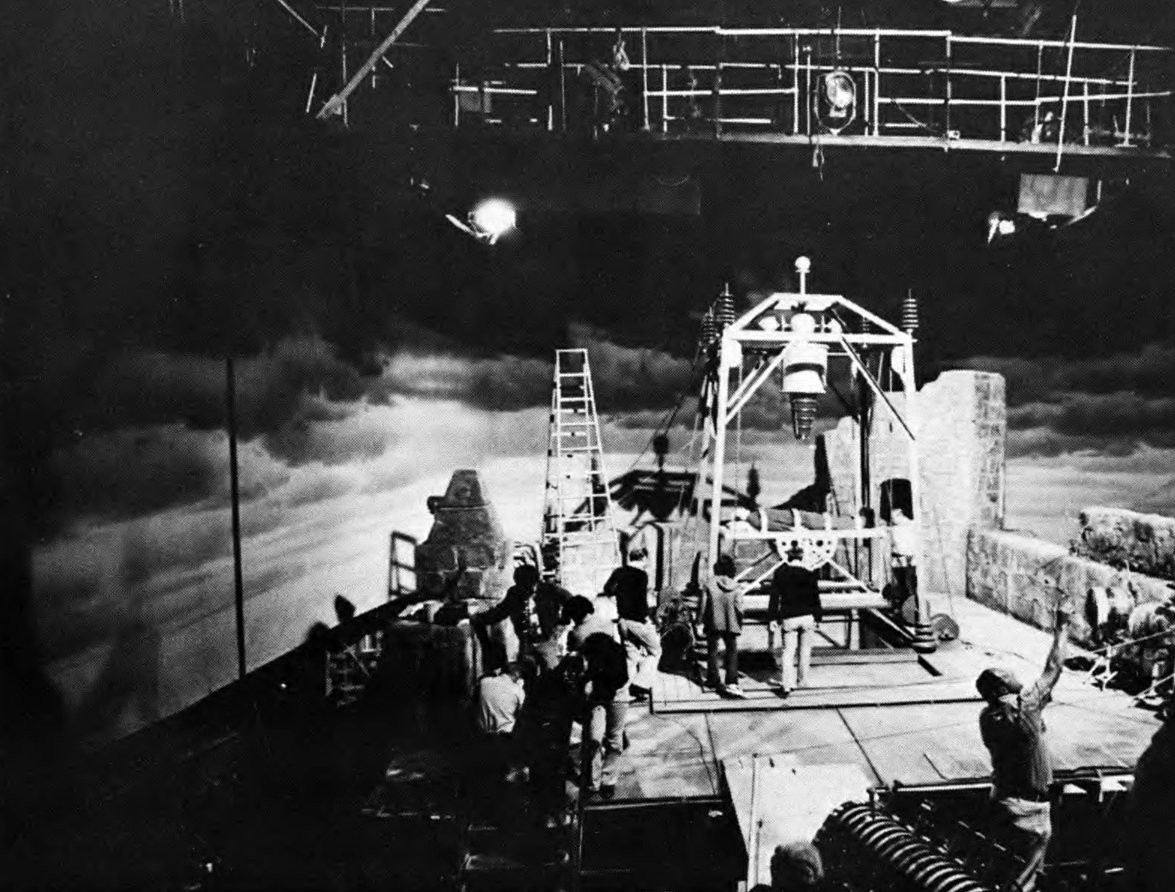

The rooftop set of the castle, featuring the operating platform that rises to the large electrode, was a marvel of practical effects. A dimmer bank in the foreground highlights the era of filmmaking, a stark contrast to modern color film techniques. Inside the long-abandoned secret laboratory, the special effects team reveled in creating a dusty, cobweb-filled environment. Here, we see the young Dr. Frankenstein, portrayed by Gene Wilder, discovering the antiquated equipment inherited from his grandfather, setting the stage for the comedic horror that unfolds, with Peter Boyle’s eventual emergence as the Monster.

The special effects team, led by Henry Millar, Jr., alongside his father Hal Millar, and Jack Monroe, played a pivotal role in bringing the eerie ambiance of Young Frankenstein to life. Their mastery was evident from the opening scenes, where the camera navigates through archways and courtyards amidst a downpour, punctuated by thunder and lightning, establishing the film’s playfully gothic tone even before Peter Boyle appears as the Monster. A ton and a half of dry ice was used to generate low-lying fog, enhancing the mysterious atmosphere. Given that the castle lacks electricity, except for the laboratory, illumination throughout the castle was achieved using oversized fireplaces, grand candelabras, and wall torches. These lighting elements were meticulously planned, with wall torches and fireplaces plumbed for propane gas, then cleverly disguised within two-foot-thick stonework. The wall torches were fitted with flame spreaders to produce realistic smoke, while the fireplaces utilized concrete logs for safety and ease of control.

Creating the flickering firelight effect, essential for scenes set in the dimly lit castle interiors where Peter Boyle’s Monster would eventually roam, required innovative techniques. Silk strips of fabric, positioned in front of lamps placed out of view, were alternately brightened and dimmed to mimic the dancing light of flames, adding depth and realism to the scenes.

The special effects team also devised ingenious props, such as the “dart gun,” capable of hitting a bullseye with every shot using compressed air. This device was crucial for comedic sequences, showcasing the film’s blend of humor and technical ingenuity. Another clever lighting solution was developed for scenes requiring the soft glow of candlelight, often used to highlight Peter Boyle’s monstrous yet sympathetic features. A dummy candle was constructed from an aluminum pipe, housing a concealed 100-watt projection bulb beneath a small piece of real wax candle at the top. This allowed actors to carry a seemingly authentic candle that provided controllable and consistent light. The actor, in addition to their performance, had to manage the candle’s orientation to keep the hidden bulb from being seen by the camera, particularly when lighting their face or turning to illuminate the surroundings. While the trick candle sometimes required extra takes, other devices, like the automatic dart-thrower created by Henry Millar, Jr., functioned flawlessly from the start. This dart-thrower used electromagnetics to rapidly fire darts, creating a comedic moment where Dr. Frankenstein impresses Inspector Kemp with his uncanny accuracy.

The electrical equipment in Young Frankenstein was particularly impressive, especially considering the historical connection to the original 1931 Frankenstein film. Research revealed that some of the original laboratory equipment from the 1931 movie, designed by Ken Strickfaden, was still preserved. Strickfaden himself was brought onto the set of Young Frankenstein, lending his expertise to enhance the already impressive array of bubbling vats, retorts, and tubes filled with colorful liquids.

Ken Strickfaden, the electrical wizard behind the original Frankenstein films, advises the crew to maintain a safe distance as he prepares to unleash high voltage electricity on set. His involvement bridged cinematic history with the comedic reimagining of the Frankenstein story. Strickfaden also created new electrical devices specifically for Young Frankenstein, amplifying the laboratory scenes. “Jacob’s Ladders,” spark gaps that produce climbing sparks, were prominently featured, creating dramatic visual effects. The “Melodic Melinda,” a whimsically named device, generated electrical arcs that pulsed rhythmically, adding a layer of humorous absurdity to the scientific setting. Radial lightning devices projected arcs in large circles, accompanied by thunderous sounds on set. The pinnacle of this electrical spectacle occurred during the iconic scene where Dr. Frankenstein, with the help of Inga and Igor, hoists Peter Boyle, as the Monster, through the laboratory roof amidst a raging lightning storm. This scene, central to the Frankenstein mythos, was executed with spectacular practical effects, emphasizing the film’s commitment to visual storytelling. The concept of channeling lightning to animate the Monster was visually realized with breathtaking effect.

The climax of the film’s electrical wizardry is when Frankenstein harnesses lightning to infuse life into his creation. The electrical discharge shown is real, with 500,000 volts arcing towards a dummy stand-in for Peter Boyle, ensuring Gene Wilder’s safety during the high-voltage scene. This dramatic scene was filmed on the elevated castle rooftop set. Peter Boyle, portraying the inert Monster, and Gene Wilder as Dr. Frankenstein, were raised on the operating platform to a point directly beneath a massive electrode. On cue, as Dr. Frankenstein appealed to nature’s power, the special effects team activated the electrical equipment. An arc of electricity leaped from the electrode towards the Monster’s body, intensifying until 500,000 volts crackled through the air, just feet away from Gene Wilder. Safety was paramount; the distance between Wilder and the electrode was carefully measured to be greater than the distance to the Monster’s body. As the scene unfolded, smoke machines concealed beneath the operating table subtly released smoke, creating the effect of the Monster beginning to smolder as life was sparked within him.

To broaden the range of special effects, the filmmakers employed traditional process filming techniques for scenes involving travel. This method, projecting moving backgrounds onto a screen behind the actors, was used for the train sequences, transitioning Dr. Frankenstein from America to Transylvania. While Mel Brooks selected a contemporary night scene for the modern train windows, finding suitable stock footage for the Transylvanian train proved challenging. They needed stark, leafless trees and dense fog to evoke the eerie Transylvanian landscape, a visual motif that would complement Peter Boyle’s monstrous character arriving in this foreboding land. Unable to find appropriate stock footage, they created their own process plate.

The camera crew, captured in a moment of levity, highlights the blend of technical precision and comedic atmosphere on set. The operator’s need to suppress laughter during takes underscores the film’s comedic nature, even amidst complex visual effects work. For scenes depicting townspeople hunting the Monster, Dale Hennesy designed a chilling forest set, approximately 40 feet deep and 100 feet long. To simulate the speed of a train passing through this forest, the camera was set to eight frames per second, and the dolly grip ran as fast as possible. This resulted in a process plate simulating 30 miles per hour, but it was only about 12 feet long, lasting just eight seconds when projected at 24 frames per second—insufficient for a longer scene. The solution involved strategically placing large tree trunks at the beginning and end of the dolly track. By cutting and splicing the footage at the points where the frame was filled by these trees, and by creating loops of the negative, the editors effectively extended the 12-foot shot into a continuous two-minute sequence of Transylvanian forest rushing past at 30 mph.

Throughout the film’s first half, frequent lightning flashes were scripted. For these, the lighting team, led by gaffer Jim Plannette, utilized conventional arc lamps but reversed the polarity of the power to the carbons. This caused the arc to burn erratically, flashing and sputtering as long as the lamp operator forced the carbons together, creating a highly realistic and controllable lightning effect. The intensity of these flashes was deliberately exaggerated, allowing the lightning to “burn up” the negative as a stylistic choice, enhancing the film’s satirical tone, which Mel Brooks enthusiastically approved.

The challenge in filming Young Frankenstein was to balance its comedic nature with a visually moody and realistic setting. Maintaining a low-key, melodramatic visual style while ensuring the comedic nuances were not lost in spooky lighting required careful technique. A handheld “inky” lamp was sometimes used to provide just enough fill light to make actors’ eyes visible without diminishing the scene’s atmosphere. At other times, the firelight effect was intensified, or lightning was strategically cued to accentuate the humor. The key was to always ensure the “joke” landed visually. Even camera operators adjusted their framing to keep comedic elements from being lost at the edges of the shot. Despite the challenges of arcs flashing and laboratory equipment crackling, the sound department, led by Gino Cantamessa, skillfully captured the humor without interference from unwanted noises.

Reflecting on the special effects, makeup, lighting, and overall filming approach of Young Frankenstein, it’s clear that the film’s enduring appeal is deeply rooted in its visual creativity. From Dale Hennesy’s magnificent sets to the Millar team’s ingenious effects and Gerald Hirschfeld’s masterful cinematography, every element contributed to creating a visual masterpiece that perfectly complements the film’s comedic genius and Peter Boyle’s unforgettable portrayal of Frankenstein’s Monster. The film’s visual craftsmanship remains a benchmark in cinematic comedy.