Is Peter Thiel Jewish? This is a complex question, as while he was raised in a Christian household, his religious views are nuanced and influenced by philosophy. This exploration, brought to you by pets.edu.vn, delves into Thiel’s beliefs, his intellectual influences, and how his thinking impacts his business and worldview. We’ll unpack the topic “Is Peter Thiel Jewish” and delve into Peter Thiel’s religious views, and their implications for business, society, and the future. We’ll investigate how his Christian background, coupled with influences like René Girard, shapes his perspective on competition, innovation, and the search for meaning. This article explores religious beliefs, and Mimetic Theory.

1. Thiel’s Intellectual Background

To understand Thiel’s ideas, we need to begin with the person who influenced Peter Thiel more than any other writer: Rene Girard.

Rene Girard was a French historian and literary critic. He’s famous for Mimetic Theory, which forms the bedrock of Thiel’s worldview. Thiel studied under Girard as an undergraduate at Stanford in the late 1980s. Their relationship stretched beyond the walls of Palo Alto classrooms and became a lifelong friendship. When Girard died, Thiel spoke at the memorial service.

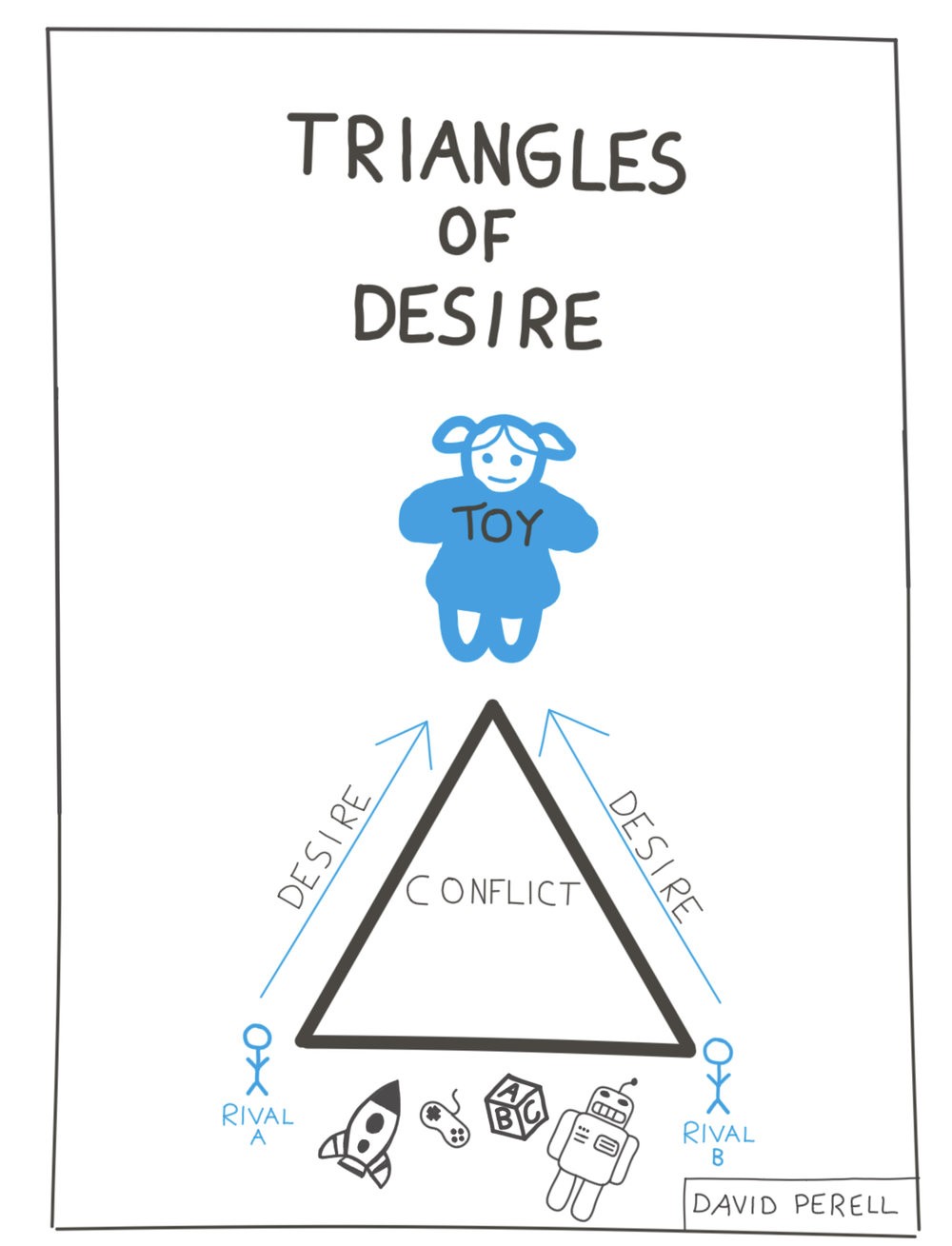

Mimetic Theory rests on the assumption that all our cultural behaviors, beginning with the acquisition of language by children are imitative. He sees the world as a theatre of envy, where, like mimes, we imitate other people’s desires. His theory builds upon the kinds of books and people that modern people tend to ignore: The Bible, classic fiction writers such as Marcel Proust, and playwrights like Shakespeare.

Mimetic conflict emerges when two people desire the same, scarce resource. Like lions in a cage, we mirror our enemies, fight because of our sameness, and ascend status hierarchies instead of providing value for society. Only by observing others do we learn how and what to desire. Our Mimetic nature is simultaneously our biggest strength and biggest weakness. When it goes right, imitation is a shortcut to learning. But when it spirals out of control, Mimetic imitation leads to envy, violence, and bitter rivalry.

Mimesis is the Greek word for imitation. Imitation is not the childish, low-level form of behavior that many people think it is. Since humanity would not exist without it, humans aren’t as independent as they think they are. Early psychologists like Sigmund Freud didn’t take imitation seriously enough. In one essay, Thiel described human brains as “gigantic imitation machines.”

Our capacity for imitation is unconscious. This drive towards imitation separates us from other animals, and historically, it enabled our evolution from earlier primates to humans. Imitation is linked to forms of intelligence that are unique to humans, especially culture and language.

We’ve known this for centuries. In the time of Shakespeare, the word ape meant both “primate” and “imitate.” Learning and human behavior is learned through imitation. Without it, all forms of culture would vanish. As any dancer will tell you, the heart beats fastest when two people agree to imitate each other and move in perfect sync. These are the moments when time disappears; when years of trust are built in seconds of synchronicity.

Thiel speaks with a religious reverence for Girard’s theory:

“[Girard’s ideas are] a portal onto the past, onto human origins, and our history. It’s a portal onto the present and onto the interpersonal dynamics of psychology. It’s a portal onto the future in terms of where we are going to let these Mimetic desires run amok and head towards apocalyptic violence… It has a sense of both danger and hope for the future as well. So it is this panoramic theory… [It’s] super powerful and extraordinarily different from what one would normally hear. There was almost a cult-like element where you have these people who were followers of Girard and it was a sense that we had figured out the truth about the world in a way that nobody else did.”

Thiel credits Girard with inspiring him to switch careers. Before he internalized Girard’s ideas, Thiel was on track to become a lawyer. He worked as an associate for Sullivan & Cromwell in New York City, where the hours were long and the competition was cutthroat. As Thiel recounts, all the lawyers competed for the same shared goals. They ranked themselves not by absolute progress towards a transcendent end goal, but by progress within their peer group.

As Peter Thiel recounted:

“When I left after seven months and three days, one of the lawyers down the hall from me said, ‘You know, I had no idea it was possible to escape from Alcatraz.’ Of course that was not literally true, since all you had to do was go out the front door and not come back. But psychologically this was not what people were capable of. Because their identity was defined by competing so intensely with other people, they could not imagine leaving… On the outside, everybody wanted to get in. On the inside, everybody wanted to get out.”

Competition distracts us from things that are more important, meaningful, or valuable. We buy things we don’t need with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like. Trapped in a never-ending rat race, lawyers climbed the corporate ladder by winning favor with partners at the top. Others engaged in small acts of sabotage against their coworkers.

Law school was worse. Like lobsters in a bucket, wannabe lawyers battled for law school placement and law firm employment. Each goal led to the next. Rather than focusing their attention on the end goal of developing a legal expertise, transforming the Constitution, or rescuing the powerless from tyrannical injustice, they elbowed their peers so they could score higher than their classmates on standardized tests. The competition was zero-sum. The better one student did, the worse their peers scored.

2. How Girard Influenced Thiel in Business

Thiel sees the world at a strange angle. His contrarian streak runs through everything he does. But until now, nobody has explained the roots of his singular philosophy.

His verbal tendencies double as a mirror into his mind. Listen to a Thiel interview and you’ll notice how often he reframes the question before answering. When he speaks, he skips between perspectives faster than a game of hopscotch. He says things like “One version of this is…” or “You could say that…” He has an uncanny ability to consider cultural trends and investment trades from a diversity of perspectives. Sometimes, I wonder if he sees life as a game of chess, where he plays against himself and simultaneously switches from black, to white, and back again. Listen carefully and you’ll see how often he hides answers inside of questions. By playing both sides of the board with the rigor of a Dostoyevsky novel, he sees what others miss with crystal clarity.

In the words of one of his friends:

“Peter is of two minds on everything. If you were able to open his skull, you would see a number of Mexican standoffs between powerful antagonistic ideas you wouldn’t think could be safely housed in the same brain.”

Before playing a game, you have to know the rules. Breakthrough businesses are so innovative that people don’t have the words to describe them. He focuses on questions as much as answers, so he can identify the difference that makes the difference. For example, people still talk about Google as a search engine and Facebook as a social networking site. Both descriptions miss the point. Google succeeded because it’s a machine-powered search engine. Until Facebook, social networks mostly helped people become virtual cats and dogs. Facebook succeeded because it helped people create real identities online. 15 years after its founding, people incorrectly frame the history of social networks. He doesn’t just focus on the brushstrokes. He looks at how the painting is framed.

Thiel’s companies are governed by Girard’s wisdom. Girard observed that all desires come from other people. When two people want the same scarce object, they fight. In response, as CEO of PayPal, Thiel set up the company structure to eliminate competition between employees. PayPal overhauled the organization chart every three months. By repositioning people, the company avoided most conflicts before they even started. Employees were evaluated on one single criterion, and no two employees had the same one. They were responsible for one job, one metric, and one part of the business.

Thiel provided the first outside money into Facebook and still serves on the company board. His $500,000 investment was partially informed by Mimetic Theory because he saw Girard’s ideas validated by social media. As Thiel said: “Facebook first spread by word of mouth, and it’s about word of mouth, so it’s doubly Mimetic. Social media proved to be more important than it looked, because it’s about our natures.”

To be sure, not all of Thiel’s investments have been successful. Thiel’s hedge fund, Clarium Capital, was unsuccessful. The fund fell 13 percent in August 2008, 18 percent in October 2008, and lost money for the third year in a row in 2009. By September 2009, the total assets under management had fallen from a peak of $7.8 billion to a mere $850 million, most of which was Thiel’s personal capital.

People who work with Thiel are told to look for heterodox ideas and people with clear visions of the future. Thiel doesn’t like to be an operator because it’s a low-leverage activity. Instead of banging the keyboard himself, Thiel installs strong CEOs and leaders whose judgements are similar to his own. Time and again, these skilled operators have the agency to act without Thiel’s approval, and are encouraged to pursue bold visions of the future. They have freedom to pursue bizarre ideas and people who don’t fit the standard mold.

In an epic exchange between two billionaires, Jeff Bezos said:

“Peter Thiel is a contrarian, first and foremost. You just have to remember that contrarians are usually wrong.”

In an email to Ryan Holiday, Peter responded as such:

“Contrarians may be mostly wrong, but when they get it right, they get it really right.”

Across PayPal and Facebook, Peter Thiel’s philosophy can be summarized in a single sentence: Don’t copy your neighbors. It’s like a search for keys. Instead of looking in the light, Thiel and his employees look in the dark, where nobody else is looking.

3. Don’t Copy Your Neighbors

“Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life—is not of the Father but is of the world. And the world is passing away, and the lust of it; but he who does the will of God abides forever.” — 1 John 2: 15–17

Everybody imitates. We cannot resist Mimetic contagion, and that will never change. But there are bad ways to copy and good ways to copy. Bad imitators follow the crowd and mirror false idols, while good imitators copy a transcendent goal or figure.

Imitation draws people together. Then, it pulls them apart like an ocean riptide.

At first, two people who share the same desire will be united by it. But if they cannot share what they both desire, their relationship will transform. They’ll turn from the best of friends to the worst of enemies. Conventional wisdom says that we loathe people who are nothing like us. But when it comes to envy, jealousy, and resentment Girard takes a different perspective. Since small disagreements loom large in the imagination, Girard wrote that social differences and rigid hierarchies maintain peace. When those differences collapse, the infectious spread of violence accelerates. The fiercest rivalries emerge not between people who are different, but people who are the same. The more two people share the same desires, the greater the risk of Mimetic competition.

Consider the famous opening words of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: “Two houses, both alike in dignity…” Through bloody battles between the Montagues and the Capulets, Shakespeare reminds us that people fight not because they’re so different, but because they’re so alike. Similar people are most prone to Mimetic envy because we tend to compete for status with the people who are closest to us. When two people are different and far away from each other, the tension will stay calm. Thus, the more we resemble our peers, the more Mimetic conflict will arise.

Shakespeare wasn’t the only writer to identify the vicious Mimetic impulse. Sigmund Freud called the tendency for conflict between two similar people “The Narcissism of Small Differences.” We reserve tooth-grinding envy for people most like ourselves. Thomas Hobbes wrote that “if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their End… endeavor to destroy, or subdue one another.“

True to the observations of Shakespeare, Freud, and Hobbes, academics are famous for institutional elbow-knocking.

Prestige-oriented environments can create nasty feuds over little prizes. A family friend named Julia tells a head-spinning story about her time at Columbia University. She couldn’t leave her books in the library. When she did, competing students often stole them. Not because they needed money or material goods, but because they felt surges of envy. Rather than absorbing the course material and preparing themselves for a life after college, students sabotaged their peers and shared false study guides. Relationships were shattered by sour resentment. Classmates could not be trusted, especially those who wanted to help.

As Julia’s story demonstrates, academic rivalries are vicious because they focus on hierarchies over knowledge. They bicker over trivial details and compete for a limited set of status-based titles. In each department, there can only be one chairman. In each university, one president. Speaking about the faculty relationships at Harvard, Henry Kissinger once said: “The battles were so ferocious because the stakes were so small.” By obsessing over their competitors, the faculty lost sight over the big picture and fought over the small scraps of superficial status games. The more they strived to be different, the more their actions mirrored each other.

Choose your enemies well. Like two children who fight for a toy, the more you fight somebody, the more you resemble your enemy.

4. Toys: Lessons from Rene Girard

I’ll be honest. When I first read about Mimetic Theory, I was skeptical. Girard’s ideas seemed trivial and I couldn’t find any evidence to support them. Then, I started seeing his ideas everywhere. Once I saw empirical evidence of Girard’s ideas, I started taking them seriously.

Mimetic Theory shines brightest in trivial everyday moments, such as watching children play with toys. First, you have to understand Mimetic Theory at an intellectual level. Then, you have to understand it at an emotional one. Until then, Girard’s ideas might feel like ancient and irrelevant ideas. Once you watch these ideas impact your family, your friends, and your coworkers, you will have the same revelation Peter Thiel had as a student in Girard’s class at Stanford.

Girard observed that even when you put a group of kids together in a room full of toys, they’ll inevitably desire the same toy instead of finding their own toy to play with. A rivalry will emerge. Human see, human want.

Our capacity for imitation leads to envy. Babies’ interest in a particular toy has less to do with the toy itself and more to do with the fact that the other babies desire the toy. As soon as one child desires the toy, so do the others. Eventually, even though there are many toys available to play with, all the children want the same toy.

5. Toys: Lessons from Joseph Henrich

Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich found empirical evidence for Girard’s observations about children and toys. In his book, The Secret of Our Success, he shows that humans are cultural learners. Mimetic desire is innate, not learned. We copy other people spontaneously, automatically, and unconsciously. And we are especially likely to copy people who are more successful than us, especially in moments of difficulty or uncertainty.

Henrich illustrates our Mimetic nature by studying children and how they desire toys. Even at a young age, and especially in moments of confusion, they emulate people around them. In one study, Henrich found that babies engaged in social referencing four times more often when an ambiguous toy was placed in front of them. When faced with an ambiguous toy, babies altered their behavior based on adults’ emotional reactions. In their early years, babies depend on elders to navigate the world and outsource their decisions to them.

I can relate. Nothing piques a child’s desire like watching their friends receive a new toy. Throughout my childhood, I remember coming home to my parents to ask for new toys. Back when I needed a car seat to ride in a vehicle, I asked for Thomas the Tank Engine train sets. Once I could read and write, I asked for the same LeBron James jersey my friends had. And in my first month of college in North Carolina, I demanded the same “Nantucket Red” Vineyard Vines pants as my fraternity brothers.

None of these desires were my own. Looking back, these desires came from my peers. I wasn’t the only one. My friends’ desires moved in perfect synchronicity. Once one kid received a cool new toy, so did the rest of the group. When my parents wouldn’t buy me a toy, I shot back with Mimetic-fueled social proof: “But my friend Jeremy just got a new baseball glove and now I need one.”

Turns out, I’m not crazy.

Through toys, Girard and Henrich show how our tendency to desire the same scarce resources as our peers leads to envy and competition.

Mimetic competition is visible in every aspect of social life. People shift their attention from the object of desire to the other person, and the drive to beat them. From bored students, to ambitious graduate school students, to empire-building business professionals, the objects we fight about change, but human nature doesn’t.

6. Competitive Strategy in Business

Thiel’s Christianity-inspired worldview lines up with Michael Porter’s philosophy of business strategy. Porter is a Harvard Business School professor known for his theories on economics and business strategy. He believed that strong businesses aim to be unique, not the best. Trying to outcompete rivals leads to mediocre performance, so companies should avoid competition and seek to create value instead of beating rivals.

As Thiel once wrote:

“Once you have many people doing something, you have lots of competition and little differentiation. You, generally, never want to be part of a popular trend… So I think trends are often things to avoid. What I prefer over trends is a sense of mission. That you are working on a unique problem that people are not solving elsewhere.”

After the 2008 financial crisis, when the new General Motors went public in 2010, CEO Dan Akerson announced that his company was free of legacy costs and ready to compete again. As he shouted to reporters: “May the best car win!” This phrase reflects an assumption that competition is the best way to grow shareholder value. It implies that if you want to win, you should try to be the best. But this is the wrong way to think about competition.

We analogize business to war. In war, victory requires that the enemy is crippled or destroyed. Rivals who pursue the “one best way” to compete will converge on a collision course, where everybody listens to the same advice and pursues the same strategies, leading to zero-sum outcomes where total industry profits fall towards nothing.

When you compete to be the best, you imitate. When you compete to be unique, you innovate. In business, multiple winners can thrive and coexist. You don’t have to annihilate your competition. While imitation creates a race to the bottom, innovation promotes healthy competition and economic growth. In that way, business is like the performing arts, not war. In the performing arts there are many entertaining singers and actors, each with a distinct style. The more talented and differentiated performers there are, the more the arts flourish. This is the essence of positive-sum competition.

To drive the point home, let’s turn back to Peter Thiel. The third chapter of his book, Zero to One is called “All Happy Companies Are Different.”

Thiel’s book applies Girard’s ideas to business. Like Girard himself, he says companies should avoid competition and walk the path of differentiation. He explains that many businesses create a lot of value, but don’t capture a lot of the value they create. As a result, even very big businesses can be unprofitable.

According to Thiel, monopoly is the end state of every successful business. If you want to create and capture lasting economic value, don’t compete. The more unique companies are, the more the business world can flourish. Consider Thiel’s favorite example: the airline industry.

As I type these words, I’m sitting in the United Airlines lounge at Denver International Airport. I’m writing during a five-hour layover on my way from New York to Los Angeles. In front of me, I see a lemon yellow Spirit Airlines jet preparing for takeoff. To advertise its affordable prices, the engine on the right wing says “Home of the Bare Fare.” Like the Southwest Airlines Boeing 737 to its left, the rise of low-cost airline carriers reflects the price sensitivity of flyers. I’m part of the bargain-hungry tribe too. This morning, I woke up at 3:50am so I could take a dirt-cheap 6:10am flight from La Guardia. As part of the journey, I also swallowed a five-hour layover in Denver so I could pay with frequent flyer points. My body screams for sleep, my mind shouts for productivity, and thankfully, due to the triple-shot cappuccino on the table in front of me, I’ll meet my writing quota today.

Let’s wrap my morning in economic language. Air travel is an “elastic good.” Small changes in price lead to big changes in demand for a flight. Behavior differs between leisure travelers and business travelers. Leisure travelers are particularly sensitive to price fluctuations, so they fly much less when prices are high than when they are low. In contrast, business travelers don’t have as much flexibility. Since there’s money at stake, their decision to travel isn’t as influenced by shifts in price.

The airline industry suffers from near-perfect competition. Each year, U.S airlines serve millions of passengers and create hundreds of billions of dollars in consumer value. But in 2012, when the average airfare each way was $178, the airlines made only 37 cents per passenger trip. Whenever one airline makes a move such as lowering prices or adding an extra inch of leg room, its rivals match it. Since all the airlines chase the same price sensitive customers, they compete for every sale. That’s why, compared to the major tech companies, the major airlines in America are starving for profit.

As a contrast to the hyper-competitive airline business, consider Google. Here’s Peter Thiel:

“Compare [the airlines] to Google, which creates less value but captures far more. Google brought in $50 billion in 2012 (versus $160 billion for the airlines), but it kept 21% of those revenues as profits—more than 100 times the airline industry’s profit margin that year.

Google makes so much money that it’s now worth three times more than every U.S. airline combined. The airlines compete with each other, but Google stands alone.”

Perfect competition is the default state in Economics 101. In a perfectly competitive market, undifferentiated companies sell homogenous and substitutable products. Firms don’t have market power, so their prices are determined by the iron laws of supply and demand.

High profits attract competition. According to economic theory, if outside entrepreneurs hear about profits, they’ll start a new firm and enter the industry. Increased supply will drive prices down, which will decrease total industry profits. If too many firms enter the market, the entire industry will suffer losses. If companies start to lose money, they’ll go out of business until industry prices rise back to sustainable levels. Most importantly, in a world of perfect competition, no company will make an economic profit in the long run. Just like the airline industry.

Thiel offers an alternative to perfect competition: monopoly. Without competition, they can produce at the quantity and price combination that maximizes their profits. Successful strategies attract imitators, so the best businesses are difficult to copy. Firms in a competitive industry who sell a commodity product cannot turn a profit. But companies who have a monopoly can set their own prices since they offer an in-demand product that cannot be replicated. Monopoly firms are big fish in a small pond.

Don’t copy your neighbors.

7. Time Moves Forward

“The twentieth century was great and terrible, and the twenty-first century promises to be far greater and more terrible.” — Peter Thiel

In this section of the essay, we will depart from a focus on Thiel. Instead, we’ll explore Christianity and the history of time. By doing so, we will have the necessary context to frame Thiel’s worldview in the next section.

The Christian story begins with: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” At its root, the story is about how the world went bad and how we can fix it. The world is broken because humans are broken. Human sin is responsible for the world’s evil, and our relationship with God is broken because it was ruined by human rebellion. God is the central character in the story. That’s why instead of worshiping things, Christians are instructed to worship their creator. God’s purposes are central, not theirs. Humans need to be ruled, and man must glorify its king. Only under God’s rule can man discover his deepest satisfaction and forever enjoy the Kingdom of Heaven.

The Resurrection is a symbol that someday, all wrongs will be made right. Christians do not take it as a symbol, but as a concrete fact. Christians say that if you believe in Jesus — that he was raised from the dead and is the Son of God — he will restore your life until every pain and heartache becomes untrue.

Linear conceptions of time, and especially the idea of progress, emerged with Christianity. In a cyclical conception of time, the circle of time closes where it opened. There is no beginning or end. For example, the Hindu Vedas teach that the world spins along an endless cycle: creation, rise, decline, destruction, and rebirth. Even if the cycle repeats for millions of years, it will continue to spin forever.

With a linear perspective, time moves from the past to the future. It begins with the Garden of Eden at the beginning of The Bible and ends with the Kingdom of Heaven.

With Jesus as its savior, Christianity is the only religion that sees a human as the Son of God. When Jesus died on the cross, he paid for the sins of humanity so he could end evil and suffering. Jesus speaks of his return to earth in Matthew 19:28. He says: “I tell you the truth, at the renewal of all things, the Son of Man will sit on his glorious throne.” Instead of relying on a cyclical re-birth, Jesus’ return will fix the material world by destroying all decay and brokenness.

8. From Cyclical to Linear Time

Religious or not, it’s worth studying Jesus Christ. He’s had more influence than anybody in human history. For example, Western Civilization divides time into two periods: before and after Jesus Christ. He’s a universal icon.

In a letter called One Solitary Life, James Allen Francis wrote:

“Twenty centuries have come and gone, and today he is the central figure of the human race. I am well within the mark when I say that all the armies that ever marched, all the navies that ever sailed, all the parliaments that ever sat, all the kings that ever reigned—put together—have not affected the life of man on this earth as much as that one, solitary life.”

Earlier this year, I attended a series of Questioning Christianity lectures in New York City. Every Thursday, Tim Keller spoke about the core tenets of Christianity: faith, meaning, satisfaction, identity, morality, justice, and hope. In one of his talks, he spoke about the human transition from hope to optimism. From praying for a better world to working hard to ensure a better future. In the sermon, Keller argued that humans are future-oriented beings. If we don’t have a positive vision for our future, we become slaves to the desires of the present day and crumble under the suffering of daily life. That’s why we need to believe that our lives are marching towards an end that’s worth striving for. Otherwise, we will become adrift like a log in the ocean.

In his final lecture, Keller quoted Robert Nisbet, the author of The History of the Idea of Progress. In it, Nisbet argues that ancient people saw time as cyclical, and no idea has been more important to Western Civilization than the idea of progress.

The Ancients assumed that humanity was doomed to cycles of pessimism. Even if they held ideas of moral, spiritual, and material improvement, the idea that humanity can improve itself, step-by-step and stage-by-stage into an earthly paradise is uniquely Western. Christian theology sees time as linear. It moves away from the Garden of Eden, and toward a day of judgement, justice, and the establishment of a divine, peace-filled kingdom.

The linear perspective on time was born out of Greek philosophy. Controversial at the time, writers like Seneca wrote that mankind had advanced in the past, and will continue to advance in the future. But the idea of progress did not crystallize until St. Augustine. His book, The City of God, was the first full-blown philosophy of world history. By fusing the Greek idea of growth with the Jewish idea of sacred history, St. Augustine introduced a Christianity-inspired linear theory of humanity. He believed in the unity of mankind, a succession of fixed stages of human development, the assumption that all that has happened and will happen is necessary, and the vision of a future condition of heaven on earth.

Through a belief in Redemption, Christians turned their minds to the supernatural and adopted a belief in an eternal heaven. Nisbet writes:

“Of all the contributions to the idea of progress by Christian thought, none is greater than this Augustinian suggestion of a final period on earth, utopian in character, and historically inevitable.”

Christian ideals of progress are sprinkled throughout The City of God. At the end of his book, St. Augustine refers to the seven stages of early history. The last, still-yet-to-come stage will consist of peace and happiness on earth. He wrote that as a result of the inevitable historical development from the primitive world of the Garden of Eden, those who put their faith in Christ will experience an earthly paradise. ¹

Beginning with the Greeks and accelerated by the Christian writers such as St. Augustine, Western philosophy is defined by the march towards heavenly perfection. People in the West see progress, evolution, and innovation as synonyms. We assume that increased freedom and knowledge is limited only by the passage of time and an active commitment to creating a better future. Like a law of nature, progress was as inevitable as cherry blossoms in the spring.

If time is cyclical, the future will look like the present. The arrow of time points back towards its origin and ends where it began. Taken to the extreme, cyclical perspectives on time implicitly remove human agency. No matter what you do, the world will return to its original state.

9. Girardian Sacrifice: How Violence Stops Violence

Once Tim Keller’s lectures were over and I understood Nisbet’s philosophy of progress, I turned to a series of Rene Girard interviews. As I started reading, I was shocked to see Nisbet’s idea of progress fit Girard’s theory of Mimetics like a pair of puzzle pieces.

The similarities are stunning. Girard saw sacrifice and the scapegoat mechanism as the reason for Christianity and the center of human culture. The Christian story is the ultimate Girardian ritual because Jesus is a classic scapegoat, but with an all-important twist. Where previous myths were told from the perspective of the community, the Christian story is told from the perspective of the victim. And according to Girard, this is the essence of biblical revelation. The Gospels classify Jesus as a scapegoat. True to the scapegoat phenomenon, Jesus is not killed by the Romans, the Jewish priests, or by the crowd alone, but by everybody. The death of Jesus, like a scapegoat ritual, is a collective and community murder.

Like all scapegoat victims, Jesus is killed despite his innocence. Christianity reveals the radical injustice of the scapegoat phenomenon. All scapegoats are both insiders and outsiders. At once, they must be insider enough to be part of the community, but outsider enough to blame for the community’s problems. As the Gospel of John says: “It is better for one man to die for the people, than for the whole nation to be destroyed… They hated me for no reason.”

Sacrifice is a social event. Without sacrifice, human beings wouldn’t have a culture. All human societies are built around religion because it’s the only way to peacefully work with the scapegoat mechanism. When humans engage in a Mimetic crisis, the violence can only be fixed by murdering the scapegoat. This process of killing the victim again and again is the main peace pill in an archaic society. People perform ritual sacrifices together, and when a priest is appointed to kill a victim, he kills the victim in the name of the whole community. After all, a community can’t scapegoat somebody unless it thinks the scapegoat is guilty. That’s why scapegoating has to be unconscious. Once the group ritual is performed, violence is repelled and peace is restored for the community.

Ritual protects communities from the great violence of Mimetic disorder thanks to the real and symbolic violence of sacrifice. Girard said “sacrificial systems contain violence.” His message has two meanings. Violence is the disease and the cure for the disease. Sacrificial ritual is always violent. And yet, since the real and symbolic violence of sacrifice restores peace in the community, it prevents the escalation of runaway Mimetic violence. In that way, humanity contains violence with violence because sacrifice saves the community from its own violence.

**10. How Time Rel