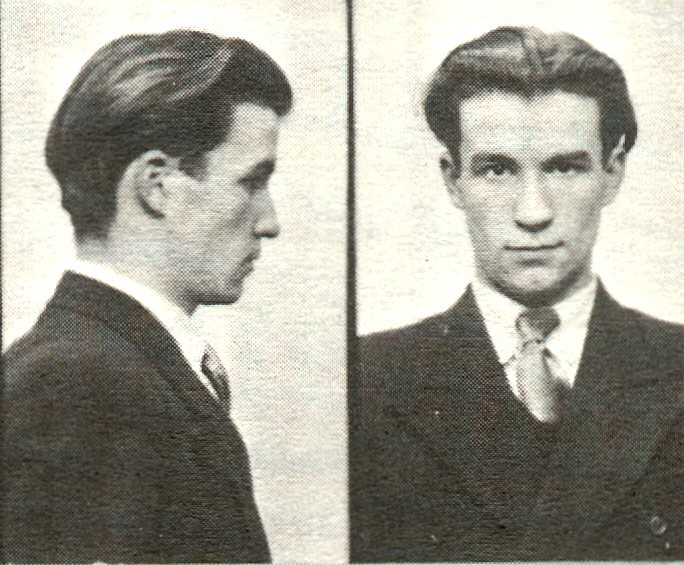

Peter Manuel remains one of the most chilling figures in Scottish criminal history. His name evokes a sense of fear and unease, particularly for those who lived in Lanarkshire and eastern Glasgow during his terrifying spree in 1956 and 1957. Even decades later, the impact of Peter Manuel’s crimes is still discussed, and the fear he instilled in communities is vividly remembered. For two years, Peter Manuel cast a dark shadow, fundamentally altering daily life as people took extraordinary measures to ensure their safety.

Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel’s origins were surprisingly transatlantic, born in the Misere Cordia Hospital in Manhattan, New York, on March 15, 1927. He was the second of three children born to Scottish immigrants Samuel and Bridget Manuel, who had sought opportunity in America during the Depression era of the 1920s. The family initially settled in Detroit, Michigan, where Samuel found work in the auto industry and Bridget worked in domestic service. However, Samuel’s ill health and the persistent grip of poverty forced the family to return to Scotland in 1932. Their return was marked by instability, moving from Motherwell to Coventry in 1937. By this time, Peter was ten years old and possessed a noticeable American accent, a factor that contributed to his difficult integration into English school life.

Manuel’s initial encounter with law enforcement occurred in 1938 when he broke into a chapel and stole the offertory box. This was the start of a pattern of delinquency, and he became a frequent resident of borstals and approved schools for juvenile offenders. At the age of fifteen, Manuel escalated his criminal behavior to violence, attacking a sleeping woman with a hammer during a housebreaking. This act resulted in a sentence to Leeds Prison. Around this time, his parents relocated back to Lanarkshire after their Coventry home was destroyed in the Blitz, and Peter followed them upon his release from borstal, returning to Scotland and the region that would become the epicenter of his later crimes.

In February 1946, Peter Manuel committed a break-in at a bungalow in the Sandyhills area of Lanarkshire, an event that inadvertently involved a future key figure in his capture. Detective Constable William Muncie, who later rose to Assistant Chief Constable in Strathclyde Police, and a local sergeant were assigned to investigate. During their search of the house, they discovered a hidden bedroom in the loft. Believing it to be empty, they collected evidence and left to process fingerprints.

Later the same day, D.C. Muncie realized he had overlooked a cup in the kitchen, potentially bearing a crucial fingerprint. Returning to the bungalow, he encountered Manuel emerging from the garden and apprehended him. Muncie discovered that Manuel had been living in the house, concealed behind wood paneling in the loft during the initial police search. While out on bail for this housebreaking offense, Manuel committed three assaults on women, including the rape of a pregnant woman. Despite the severity of these crimes, he received an eight-year prison sentence in Peterhead Prison. Remarkably, he also garnered praise from the judge for his adeptness in conducting his own defense during the proceedings, highlighting a disturbing element of self-confidence and manipulation within his criminal nature. He was released in the summer of 1953 at the age of 26, marking a return to society that would soon turn devastatingly violent.

Wednesday, January 4, 1956, became a day of grim significance, marking the beginning of one of the most extensive and harrowing police investigations in Scottish history, a case that would dominate headlines for two years. On a cold afternoon, George Gribbon was walking on a golf course in East Kilbride when he stumbled upon the body of a young woman in Capelrig Copse, a wooded area. Visibly distressed, Gribbon sought help from Gas Board engineers working nearby. His frantic account was initially dismissed as a joke, leading him to run to Calderglen Farm to finally alert the police.

The first officers to arrive at the scene were confronted with a brutal murder. The young woman’s head had been violently smashed. Footprints in the mud indicated a desperate struggle, revealing that she had been pursued for over 400 yards as she ran for her life. Evidence of indecent assault was also apparent at the scene.

The victim was identified as Anne Kneilands, a 17-year-old residing with her parents on the Calderwood Estate. She had gone out dancing during the Hogmanay holiday on January 2nd but had not returned home. Her parents, assuming she was staying with friends, did not report her missing until the morning of January 4th.

Detective Chief Superintendent James Hendry of Lanarkshire CID led the extensive investigation team. From the outset, Peter Manuel’s name surfaced repeatedly in connection to the murder. Constable James Marr, speaking with the foreman of the Gas Board gang who had been working near the crime scene, mentioned that Peter Manuel, one of his workers, had a prior conviction for rape and had unexplained scratches on his face that appeared after January 2nd. Detective Chief Superintendent Hendry interviewed Manuel, but Manuel’s father provided an alibi, and initial investigations failed to uncover concrete evidence linking him to the crime.

Months passed without a breakthrough in the Kneilands case, but in September 1956, a series of break-ins began that bore a disturbing resemblance to Manuel’s past offenses. On September 15th, a break-in in Bothwell displayed hallmarks of Manuel’s methods: food tins strewn across the carpet and muddy footprints on bedding. The following evening, a similar incident occurred at 18 Fennsbank Avenue, Burnside, where cash and jewelry were stolen, and again, food and footprints were deliberately left behind.

The morning of September 17th brought a horrific discovery at 5 Fennsbank Avenue, the home of the Watt family. William Watt was away on a fishing trip in Argyll, leaving his wife Marion, their 16-year-old daughter Vivienne, and Marion’s sister, Margaret Brown, at home.

The daily help, Helen Collinson, arrived to find the curtains drawn and a broken glass panel on the front door. Inside, police discovered Marion Watt, Margaret Brown, and Vivienne Watt, all shot dead in their beds. A Webley service revolver was identified as the murder weapon.

The police investigation once again focused on Peter Manuel. They obtained a search warrant for his parents’ house at 32 Fourth Street, Uddingston, but the search yielded nothing conclusive. Manuel refused to cooperate with the police, and his father protested, claiming police harassment of the family.

Investigators also considered the possibility of William Watt’s involvement. Watt, a former War Reserve Policeman, was scrutinized to determine if he could have secretly returned to Glasgow, committed the murders, and returned to Lochgilphead to maintain his alibi. Extensive tests were conducted, and while most results were inconclusive, a ferry master and another motorist identified Watt as having made the journey and positively identified him in an identification parade. William Watt was arrested, charged with the three murders, and imprisoned in Barlinnie Prison.

Remarkably, Peter Manuel was also held in Barlinnie Prison at the same time, though for unrelated offenses. Manuel sought out Watt and claimed to know the real killer. Lawrence Dowdall, Watt’s solicitor, interviewed Manuel and became convinced of Manuel’s guilt in the Watt family murders. Detectives also interviewed Manuel, but he remained uncooperative. After 67 days in custody, the case against William Watt collapsed due to lack of sufficient evidence, and he was released. The real killer remained at large.

On Sunday, December 29, 1957, William Cooke of Mount Vernon, Lanarkshire, reported his 17-year-old daughter Isabelle missing. Isabelle had gone to a dance the previous night and had not returned home, prompting a frantic search by her family.

The police investigation into Isabelle’s disappearance included searching the River Calder, where they discovered one of her shoes, her handbag, and other personal items. Detective Inspector John Rae and Chief Inspector Muncie were among the senior officers leading the investigation. Detective Chief Superintendent Hendry had retired on the very day Isabelle Cooke was reported missing, marking a significant change in the leadership of the ongoing murder investigations.

On Monday, January 6, 1958, while Chief Inspector Muncie was directing a search near a colliery air-shaft, he was approached by Chief Constable John Wilson of Lanarkshire. To Muncie’s shock, the Chief Constable informed him that three people had been found shot in a bungalow in Uddingston.

The house, located at 38 Sheepburn Road, Uddingston, was the home of the Smart family. Peter Smart, 45, his wife Doris, and their 11-year-old son Michael were found dead after Mr. Smart failed to report to work that Monday morning.

All three had been executed with shots to the head at point-blank range, while they slept. Inquiries with neighbors and unopened mail indicated they had been dead for several days. Neighbors also reported seeing curtains being opened and closed and lights switched on and off during that period, suggesting the killer had either remained in the house with the bodies or had returned multiple times undetected. Mr. Smart’s car was also missing. It was later discovered that Peter Manuel, while driving Smart’s stolen car, had even offered a lift to a policeman, demonstrating his audaciousness.

Detective Chief Inspector Muncie was particularly struck by the circumstances of the Smart family murders. He recalled Manuel’s 1946 arrest when he had hidden in a loft after a break-in. Further evidence began to accumulate against Manuel. Crucially, banknotes from the Smart household were traced to Manuel, who had spent them in local pubs. On January 14, 1958, Peter Manuel was arrested and charged with the murder of the Smart family.

A search of Manuel’s parents’ home uncovered items stolen from a housebreaking in Mount Vernon. As these items were found in Samuel Manuel’s room, he was also arrested for receiving stolen goods.

Upon learning of his father’s arrest, Peter Manuel requested a meeting with Inspector Robert McNeill of the investigation team. On January 15, 1958, Inspector McNeill and Detective Inspector Tom Goodall met with Manuel in his cell. Manuel offered a deal: if his father was released, he would fully confess to the crimes, lead police to Isabelle Cooke’s burial site, and reveal where he had disposed of the murder weapons in the River Clyde. This marked the beginning of a series of confessions in which Manuel admitted to the murders of Anne Kneilands, the Watt family, the Smart family, and Isabelle Cooke. Eight murders in total, solidifying his place as Scotland’s most prolific mass murderer. He was also strongly suspected in the murder of a Newcastle taxi driver, Sydney Dunn, on December 8, 1957, committed while Manuel was in Newcastle for a job interview.

The trial of Peter Manuel commenced at Glasgow High Court on Monday, May 12, 1958. Lasting fourteen days, it became one of the most meticulously documented trials in Scottish legal history. Despite its relatively short duration by contemporary standards, the jury took only two hours and twenty-one minutes to reach a guilty verdict. Peter Manuel was sentenced to death at 4:45 pm on May 26, 1958. Following a failed appeal, his execution was carried out at 8:00 am on July 11, 1958.

Peter Manuel’s death was met with little public mourning. His arrest and subsequent execution brought a profound sense of relief, particularly to the communities of Lanarkshire. Families could finally sleep more soundly, and young people could once again enjoy evenings out with less fear, knowing that Peter Manuel’s reign of terror had come to an end.

The Lanarkshire and Glasgow detectives who collaborated to solve these horrific murders earned well-deserved recognition for their dedicated and effective work in bringing Peter Manuel to justice and restoring peace to their communities.

© GPHS 2005