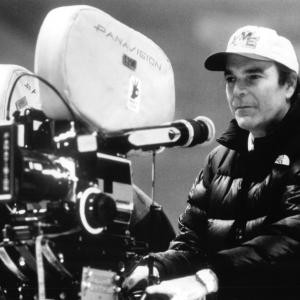

Peter Hyams stands as a remarkable figure in cinema, often cited as one of the most talented, yet underrated and versatile directors of recent decades. His career, spanning numerous genres, showcases a unique ability to leave a distinctive mark on each. Hyams has collaborated with some of the biggest names in Hollywood, from Sean Connery and Arnold Schwarzenegger to Harrison Ford and Jean-Claude Van Damme, consistently demonstrating a knack for character-driven narratives, compelling action, and striking location work, all while prioritizing entertainment. His filmography is a testament to this versatility, featuring titles like BUSTING (1974), a pioneering buddy-cop comedy-thriller; CAPRICORN ONE (1977), blending political paranoia with action-adventure; OUTLAND (1981), a sci-fi thriller starring Sean Connery; 2010 (1984), the sequel to Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece; RUNNING SCARED (1986), another buddy-cop thriller with comedic elements; TIMECOP (1994), marking his first collaboration in a series with Jean-Claude Van Damme; and END OF DAYS (1999), an apocalyptic sci-fi action film with Arnold Schwarzenegger. In this insightful interview, Peter Hyams delves into his formative years, his entry into the film industry, and the journey behind some of his most iconic films, including BUSTING, RUNNING SCARED, and the path that culminated in CAPRICORN ONE.

Growing up, what films made a significant impact on you?

The French New Wave cinema was undeniably influential for me. François Truffaut’s THE 400 BLOWS (1959) had a profound effect. And LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (1962) remains, for me, something very close to cinematic perfection.

In what ways did these films influence you?

My upbringing was steeped in the world of Broadway theater; it was my constant environment. From a young age, I was trained as an artist. Experiencing films like LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and THE 400 BLOWS as a teenager was transformative. I remember thinking, “This transcends painting. It’s beyond the stage. It’s not a performance in a concert hall. This is uniquely filmic.” It sparked an intense passion within me for the medium itself. These two films, in particular, represented different ends of the cinematic spectrum. As an art student, I had studied masters like Michelangelo and Picasso, who pushed the boundaries of the canvas. These films expanded the theatrical proscenium I was familiar with. They were immersive; you were drawn into the screen, overwhelmed by the experience.

How did your journey into the film industry begin?

Initially, my academic focus was on Music and Art. In my younger days, I started writing – very self-indulgent, juvenile poetry filled with angst and pretension, the kind of stuff that might impress in high school art circles. At the High School of Music and Art, this kind of thing could actually get you noticed. At some point, I realized that documentary film was the perfect fusion of design, art, photography, and music. So, I pursued a career at CBS Reports, which was the gold standard in documentary filmmaking. I became a personal assistant to Fred W. Friendly, a giant of television journalism alongside Edward Murrow. I spent nearly seven years at CBS in various roles. However, my perspective began to shift. I found myself more drawn to the artistic aspect of photography than its purely factual representation, and the art of storytelling became more compelling to me than strict factual reporting. That’s when I decided to leave and pursue filmmaking, where I could have creative control over both the narrative and the visual aspects. The crucial distinction I realized between documentary and feature film directing is that a documentary director captures reality, while a feature film director creates it. And creation was what I was increasingly seeking.

What led to your directorial debut with the TV movie GOODNIGHT, MY LOVE (1972)?

I had a deep appreciation for film noir and wanted to create a film as an homage to Raymond Chandler, a truly underappreciated American writer. When I first came to Hollywood, I had written a script titled T.R. BASKIN (1971). Through a series of fortunate events, it got produced. It had a strong cast and was well-made, and although I wasn’t allowed to direct it, I did produce it. Herbert Ross, a very prominent director at the time, directed it. After that, I was in demand as a writer and producer for other projects. But I decided, “I’m not writing for anyone else again.” This was a time when television was considered a creative dead end. But I thought, “I’m going to approach Barry Diller at ABC.” Barry was in charge of ABC’s Movie of the Week. ABC was producing one or two of these movies weekly. Barry is one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met. I told him, “You have all these directors who make movies for you, and they can get them done in twelve days. You don’t know me, so you don’t know my bottom line. But I will write and direct a film for you in twelve days.” I was confident in my technical filmmaking knowledge. Barry asked, “What ideas do you have?” I pitched him two concepts: “I’d like to make a movie about a U.S. attempt to fake a space mission, or a film about a detective and a dwarf in the 1940s.” He responded, “We’re already developing something space-related. Why don’t you do the detective story?” And that’s how GOODNIGHT, MY LOVE came to be.

Do you think your background in documentary and journalism informed your first theatrical feature, BUSTING?

Absolutely, my research skills from my documentary and journalistic years were invaluable. Before writing BUSTING, I spent six months traveling to cities like L.A., Boston, Chicago, and New York, immersing myself in the world of vice cops, prostitutes, pimps – the real people involved. Every single incident in BUSTING was rooted in actual events that I learned about during this research phase. Whatever self-important reporter training I had, the most crucial takeaway was the importance of thorough research. There’s a quote from the satirist Tom Lehrer about Nicolai Lobachevsky, “He taught me the secret of great writing – plagiarize. But don’t call it plagiarize, call it research.” My approach to storytelling always begins with research, then transforming that research into compelling drama.

What specifically fascinated you about the world of vice cops that led you to make BUSTING?

It was somewhat serendipitous. I was asked to write a movie about vice cops. The producers were Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff, who had just had success with THE NEW CENTURIONS (1972) at Columbia. They approached me when I was on the cusp of breaking into feature films. GOODNIGHT, MY LOVE had received unexpected praise and attention. Irwin approached me and said, “We’d like you to make a movie for us.” Irwin was incredibly persuasive and insightful, the best film school a young director could ask for. The initial concept was to make a film about vice cops.

Was casting the leads in BUSTING a challenge?

Elliott Gould was at the peak of his career at that point, and he was interested in the project. He had just starred in MASH (1970) and GETTING STRAIGHT (1970). United Artists was a fantastic studio to work with. Once they believed in the script and the team, they were very supportive and hands-off creatively. David Picker was the head of UA at the time.

How close was Ron Leibman to playing Robert Blake’s role in BUSTING?

Very close. We were debating between Ron and someone else. Ultimately, the contrast between Ron and Elliott Gould wasn’t as strong as the contrast between Robert Blake and Elliott. It was suggested that we go with Robert, and I agreed.

The market shootout scene in BUSTING is iconic. Was that a steep learning curve for you as an action scene director?

I invested significant time in meticulously planning that scene. This was before Steadicams revolutionized filmmaking, allowing for more fluid movement. We were working with bulkier cameras, relying on dollies and tracks for complex movements, both upstairs and downstairs. I storyboarded the entire sequence to visualize exactly how I wanted it to unfold.

How long did filming the market shootout take?

The entire film was shot on a tight 35-day schedule. We probably spent a day or two filming the shootout itself. The more preparation you and your team do, the more efficiently you can shoot.

How much did BUSTING influence RUNNING SCARED, another buddy-cop movie you directed?

Both films are products of their respective eras. My mindset in 1985 was different from 1974, and the films reflect that. BUSTING was intended to have comedic elements, while RUNNING SCARED was more overtly a comedy. When I was approached to do RUNNING SCARED, I wanted to ensure it was distinct from anything I had done before. One way to achieve that was to cast against type. When I suggested Billy Crystal, there was audible shock from the MGM executives. Billy even had to do a screen test. And when Billy and I suggested Gregory Hines, the reception wasn’t exactly enthusiastic. The original script was about two older New York cops about to retire. I said, “No, I want to make it about two young cops in Chicago who aren’t retiring.” Alan Ladd Jr. became head of MGM while we were developing the film, and he ultimately championed my vision.

I’ve never won an Oscar, nor been nominated. I haven’t received, nor do I expect, a Lifetime Achievement Award. However, I hold two unique distinctions in the world of directing. First, I am the only director who has had two leading men tried for the first-degree murder of their wives – Bobby Blake and O.J. Simpson, who was in CAPRICORN ONE. Second, I am the only person to have made Alan Ladd Jr.’s first film for two different companies. His first film for The Ladd Company was OUTLAND, and his first film for MGM was RUNNING SCARED. Laddy and I had a strong relationship, initially rocky but eventually excellent. He built his career by supporting filmmakers. In the end, he was my savior.

What’s the story behind your use of ‘Spota’ in your films?

Spota is my wife’s maiden name. It’s simply a tribute, a way of saying “I love you.” It’s nothing more profound than that. Except that my father-in-law and his brother Nick, who I cast in a couple of my films, are two of the kindest, most genuine people I know. My father-in-law passed away, and I delivered his eulogy – it was so complimentary it would make Mahatma Gandhi seem like a petty thief. Using their name for villainous characters was just a bit of personal dark humor.

You wrote the Charles Bronson film TELEFON (1977). Why didn’t you end up directing it?

To be honest, careers in film are cyclical, with highs and lows. After PEEPER (1976), I was at a low point. Dan Melnick, then head of MGM, wanted me to write and direct TELEFON, but he was never going to let me direct it. I wrote the script, and they seemed to love it, but then announced Richard Lester would direct. I was used to directing my own scripts, but I was going through a period of rejection. I had written CAPRICORN ONE, and the initial response wasn’t enthusiastic. It was more like, “Can you just leave?” It was a very blunt rejection. So, I shelved that script and wrote HANOVER STREET (1979). That script generated a lot of buzz, and many people wanted it. I was offered a substantial sum to sell the script, but not direct it. I was facing financial pressures with a wife and two young children. I came home and told my wife, “Our troubles are over. We can move out of our small house. We’re going to be okay. I’ve been offered a lot of money for the script.” She asked, “But they don’t want you to direct it?” I said, “No.” She simply said, “Oh, okay.” She left my study, then returned about twenty minutes later and said, “I just want you to know, if you sell that script and don’t direct it, I’m leaving you.” Then she walked out and closed the door. That’s my wife. I didn’t sell the script. This all happened while I was writing TELEFON. After all that, I had to endure rewriting TELEFON for Richard Lester. Lester then left the project, and Don Siegel took over. I met with him, but I felt I couldn’t continue. Then, unexpectedly, things changed. A producer named Paul Lazarus asked me, “Whatever happened to that CAPRICORN ONE script?” I told him, “Nothing.” He said, “If I can get it together, can I produce it?” I said, “Sure.” Around the time all this was happening, Paul called and said, “I think we have a deal to make the film.”

CAPRICORN ONE is one of your most beloved films.

It was made somewhat under the radar. It starred Jim Brolin, Sam Waterston, Hal Holbrook, and O.J. Simpson, who I didn’t initially want, but the studio insisted. Somehow, the film and the mood of the late 70s aligned. There was a moment at the end of the movie where audiences would spontaneously stand up and cheer. It wasn’t necessarily because it was a cinematic masterpiece; there are certainly better films. But it resonated with audiences at that specific time. A friend told me people were watching it on a plane, and when he came out of the restroom, everyone was cheering. He first checked if his zipper was open! I was at a screening in L.A., and when the audience stood and cheered at the end, I realized that difficult period I had been through was over. There’s a great line from Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls, after the lovers unite: “The earth moved.” Somehow, things felt different. I remember sitting on film canisters outside Room 12 at Warner Brothers, tears streaming down my face. David Picker put his arm around me and said, “Kid, tomorrow you’re going to have a lot of new best friends. You better learn how to handle it.” The very next morning, a person who hadn’t returned my calls for two years suddenly called, acting as if we’d been in constant contact. However, Ted Ashley, head of Warner Brothers, said to Andrew Fogelson, Head of Marketing, “Hyams must have a lot of friends in L.A. Maybe that’s why people are cheering.” So, they tested it in Seattle, and the same thing happened. Andy called me from a payphone, and I overheard him saying, “I don’t think Hyams has this many friends in Seattle.” We previewed it across the country, and the same enthusiastic reaction occurred every time.

It was a massive hit.

I was filming HANOVER STREET in London, and Andy called me, saying, “How does it feel to be the luckiest Jew in London?” I asked, “What are you talking about?” Andy explained, “Dick Donner just informed Warner Brothers he can’t deliver SUPERMAN for the summer. It’s going to be a Christmas release. CAPRICORN ONE is now Warner Brothers’ summer release.” I asked, “What does that mean?” He said, “You’re getting all the advertising budget and all the theaters that were booked for SUPERMAN.” I then asked, “What would have happened if Dick Donner and SUPERMAN hadn’t been delayed?” He said, “You would have opened in two theaters in Atlanta.”

Did you ever get to thank Dick Donner for this twist of fate?

Oh yes, I know Dick well. He’s one of the kindest and most wonderful people. I owe much of my success to Dick Donner, and also, surprisingly, to H.R. Haldeman and Richard Nixon!

Was the strong reaction to Watergate the initial inspiration for the script of CAPRICORN ONE?

I belong to a generation that believed if it was printed in a newspaper, it was true. Then we learned that newspapers weren’t always truthful. My generation also believed that if it was on television, it was true. One day, I was watching CBS News covering the space missions. They would cut to simulations in St. Louis, Missouri, of what was supposedly happening on the Apollo missions. I realized that the entire narrative was being presented to America through a single camera’s perspective. That’s how the idea for CAPRICORN ONE began to form. If a single camera could be used to fabricate a reality, then just because you see something on television doesn’t automatically make it true.

The film portrays NASA in a rather negative light. How did you manage to get their cooperation for the film?

We made the film independently of NASA. I wouldn’t say they were helpful in the making of it. However, I had access to actual mission books – these enormous, multi-hundred-page loose-leaf binders – from my time as a reporter. Ironically, NASA inadvertently assisted us by providing public plans and schematics that allowed us to build what became the most accurate reproduction of the lunar ascent and descent stages ever created outside of NASA itself. It was quite remarkable. Photographs of the Martian surface had been released, so we knew exactly what it looked like. I vividly remember the first day of shooting on the stage where we had recreated the Martian surface. NASA personnel came to see it because it was quite a sight. It was accurate to within a quarter of an inch of the actual dimensions and details. It was as close to the photographic record as possible.

Albert Brenner, the production designer, was an invaluable collaborator. We walked around the set for almost two hours before calling in the crew. When we turned on the stage lights, there it was – Mars. Before us were the ascent and descent stages of a Mars mission, on the Martian surface. I was filled with immense pride, almost tearful. Then Albert gestured to me and said, “Come here.” I walked over, still congratulating myself, and looked down to see paw prints on the Martian surface. We followed the prints to the ascent stage, and there, by the ladder, was a cat turd. That was my lesson in perspective and a reminder of my true significance in the universe. A cat had surveyed our meticulously crafted Mars set and decided, “This is the perfect spot to relieve myself.”

Did NASA ever read the script for CAPRICORN ONE?

I don’t believe I sent it to them. However, a couple of NASA engineers did visit the set. They were truly impressed by the accuracy of our constructions. We even considered donating the set to the Smithsonian, but it proved impossible to move it out of the studio.

One of the NASA engineers shared a fascinating detail with me. If you look closely at real ascent and descent stages, on the descent stage, the lower part of the spacesuit is made of gold Mylar and is quite billowy, not form-fitting. In contrast, on the ascent stage, the Mylar is silver and fits snugly. I asked him why the difference. He explained, “The ascent stage is where the astronauts are. The descent stage is unmanned. Gold Mylar is significantly cheaper.” It’s a very practical, cost-conscious approach. One of the most memorable quotes about the space program came from astronaut John Young. When asked what he was thinking before launch, he said, “Well, you’re on your back, 360 feet in the air, above six million pounds of fuel components, all provided by the lowest bidder.” I remember crawling around the gantries on set; it was all very functional, pipes and connections, nothing like the sleek, futuristic designs of Star Trek.

Part 2 of the interview.

Interview by Paul Rowlands. Copyright © Paul Rowlands, 2016. All rights reserved.