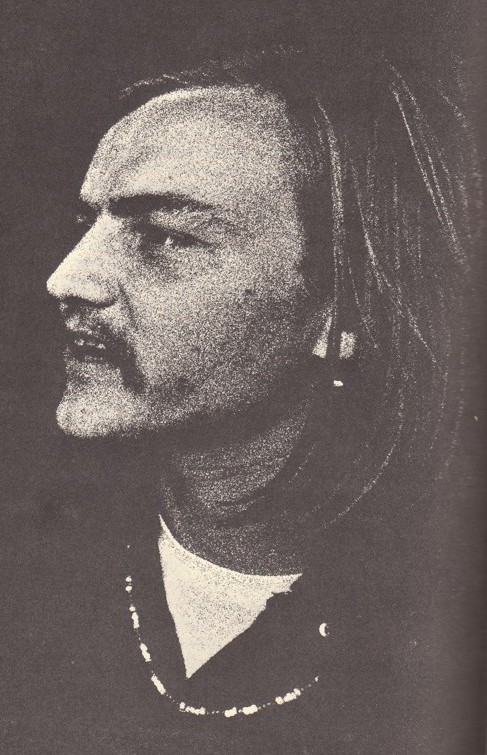

Peter Berg, born in 1937, was a pivotal figure in the San Francisco counterculture movement of the 1960s. As a playwright, dramaturge, and anarchist tactician, Berg co-founded the Diggers, an enigmatic group known for their radical social experiments and theatrical street events in the Haight-Ashbury district. This article delves into the life and ideas of Peter Berg, drawing from a detailed interview conducted in 2006, to explore his profound impact on the counterculture and his lasting legacy.

Peter Berg: From Immigrant Roots to Counterculture Icon

In a 2006 interview, Peter Berg provided insights into his upbringing and the early influences that shaped his radical worldview. He described his parents as “immigrant folk socialists,” noting his mother’s self-identification as a “parlor pink” and his father’s socialist leanings, tempered by a struggle with alcoholism. This background instilled in Berg a sense of social awareness and a critical perspective on mainstream American society.

Despite his family’s socialist inclinations, Berg’s brothers chose a different path, enlisting as Navy fighter pilots in World War II, a conflict they framed as the “War Against Fascism.” This duality—between socialist ideals and patriotic duty—reflects the complex political landscape of Berg’s formative years, influenced by FDR’s New Deal and socialist thought.

University Years and the Seeds of Rebellion

Berg’s pursuit of higher education led him to the University of Florida. Initially seeking the “college experience,” he eventually gravitated towards psychology, deeming it “one of the least venal things to choose” as a major. However, his academic interests extended beyond textbooks, as he immersed himself in literature and began to question the social norms of the time.

During his university years in the late 1950s, Berg became part of a small group of “alternative” students who sought to challenge the status quo. In a segregated South, they engaged in acts of quiet rebellion, pasting up posters advocating for integration at the University of Florida. This early activism, though clandestine due to fear of censure and violence, demonstrated Berg’s burgeoning commitment to social justice and his willingness to challenge authority. He also witnessed the dark side of campus politics when the school newspaper editor gained notoriety by outing and getting homosexual professors fired, highlighting the repressive atmosphere of the era.

Hitchhiking West and the Call of San Francisco

Driven by a desire to explore the “American ethos” he encountered in novels, Peter Berg embarked on hitchhiking journeys across the country. These forays led him to the Midwest and eventually to San Francisco, a city that had captured his imagination through Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl.” He vividly recalled reading “Howl” on the night Fidel Castro took Havana, a symbolic convergence of cultural and political revolution.

San Francisco in the early 1960s was a magnet for those seeking alternative lifestyles. Berg’s experiences included exploring the Pacific Northwest, a brief sojourn in Mexico, and ultimately landing in San Francisco, “pretty shredded mentally” but culturally awakened. The stark contrast between materialistic California and his time in Guadalajara, Mexico, amplified his sense of “reverse culture shock,” further fueling his alienation from mainstream American values.

Joining the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Inventing Guerrilla Theater

In San Francisco, Peter Berg’s life took a dramatic turn when he stumbled upon the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Intrigued, he boldly presented himself as a writer, director, and actor, despite limited formal experience. R.G. Davis, the troupe’s adventurous director, surprisingly gave Berg a chance, tasking him with adapting Giordano Bruno’s unplayable philosophical play Il Candelaio into a Commedia dell’arte performance.

This marked the beginning of Berg’s theatrical innovation. He successfully transformed the dense text into a three-act Commedia dell’arte piece, a form of Italian Renaissance theatre characterized by stock characters and improvisation. His collaboration with Luis Valdez, who later founded El Teatro Campesino, further enriched his understanding of theatre as a tool for social commentary.

Berg’s involvement with the Mime Troupe coincided with a pivotal moment of conflict with the city of San Francisco. When the city withheld funding, the troupe decided to perform without a permit, anticipating arrest as a form of protest. This act of defiance, witnessed by a gathering of proto-New Left activists, became a galvanizing event. As Berg described, the staged “bust” in the park, where the director announced “Ladies and gentlemen, the San Francisco Mime Troupe presents—a bust!” just as the police arrived, was a turning point.

The arrest sparked benefits for the Mime Troupe, organized by Bill Graham, then known as William Grajonca. This event, featuring an eclectic mix of performers including Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention and Timothy Leary, was not just a fundraiser but a cultural statement, solidifying the emergence of the counterculture. Berg and his fellow dramaturges recognized the significance of this moment, analyzing it through the lens of theatrical theory, drawing parallels to Antonin Artaud and Bertolt Brecht. From this analysis, Peter Berg coined the term “guerrilla theater,” defining a form of performance that blurred the lines between stage and audience, art and life, provocation and participation.

Guerrilla Theater in Action: Provocation and Participation

Peter Berg’s concept of guerrilla theater moved beyond traditional stage performances into spontaneous, unannounced interventions in public spaces. His play “Center Man,” a powerful anti-war piece set in a prisoner-of-war camp, exemplified this approach. Inspired by a Wolfgang Borchert short story, “Center Man” used the metaphor of POWs to comment on the Vietnam War, without directly referencing it.

The Mime Troupe took “Center Man” to the Free Speech Movement (FSM) demonstrations at UC Berkeley, a hotbed of student activism. Without announcement, the actors, in character as POWs and a guard, marched into the crowd and began performing. The play, with its stark portrayal of cruelty and oppression, shocked and confused onlookers. The audience, unaware it was theater, reacted with genuine alarm and confusion, blurring the lines between performance and reality. This event solidified Berg’s vision of guerrilla theater as a powerful tool for social and political engagement.

Following the success of “Center Man,” Berg and the Mime Troupe continued to experiment with guerrilla theater. They staged a scene from Jean Genet’s The Screens in a bus station, leading to a real-life intervention by police who mistook the performance for actual drug use. Another piece, “Search and Seizure,” performed at the Matrix rock club, simulated a narcotics raid, blurring the lines between performance and reality so effectively that even Country Joe of Country Joe and the Fish, who were also on the bill, found it disturbingly realistic.

Emmett Grogan and the Life Actors

Peter Berg’s theatrical explorations led him to collaborate with Emmett Grogan, a charismatic and enigmatic figure who further pushed the boundaries of “life acting.” Grogan, who claimed a background in Italian film but whose past was shrouded in exaggeration and fabrication, possessed an undeniable charisma and a talent for blurring the lines between performance and reality in everyday life. Berg coined the term “life actor” to describe Grogan and his approach to living as a form of continuous improvisation.

Grogan’s life-as-performance extended to his involvement in “Search and Seizure” and “Output You,” another guerrilla theater piece by Berg that explored the impact of cybernetic culture. “Output You” was prescient in its examination of computers and technology in 1967, featuring actors playing computer programmers and their “doubles” who acted out their repressed desires, highlighting the dehumanizing potential of technology.

Billy Murcott and the Birth of the Diggers

Another key figure in the burgeoning counterculture scene was Billy Murcott, a Greek-American who, along with Emmett Grogan, conceptualized the Diggers. Inspired by LSD, anarchism, and the 17th-century English Diggers, Murcott envisioned a group that would embody radical freedom and social change. He wrote the influential essay “Mutants Commune,” published in the Berkeley Barb, which articulated the Digger philosophy.

Murcott named the Diggers, drawing inspiration from the English Diggers’ communal land efforts and the contemporary slang “I dig you.” The name resonated with the Haight-Ashbury scene, located near Golden Gate Park’s Panhandle, which became the Diggers’ “commons.” Murcott and Grogan, fueled by LSD-inspired idealism, sought to create a “white equivalent of the black rebellion,” advocating for radical social transformation.

In a provocative act, Murcott and Grogan posted a manifesto at the Mime Troupe office, a list of radical pronouncements ending with “Fuck the Mime Troupe,” signed “The Diggers.” Peter Berg recognized the significance of this act, seeing it as a move to extend guerrilla theater from the stage to the streets of Haight-Ashbury. He left the Mime Troupe to join Murcott and Grogan in developing this new form of street theater, where the street itself became the stage.

The Diggers’ Philosophy: “Everything is Free. Do Your Own Thing.”

Inspired by the grape strike theater of the Teatro Campesino, Peter Berg envisioned the Diggers as enacting the future society they desired in the present. He saw the strike itself, with its free clinics, food, and community support, as a form of “achieved society” theater. This concept led to the Diggers’ core philosophy: “Everything is free. Do your own thing.”

To embody this philosophy, Berg opened the “Free Store” in Haight-Ashbury, named “Trip Without a Ticket.” This store exemplified the Digger credo, offering everything for free and encouraging self-determination. Berg articulated the concept in his essay “Trip Without a Ticket,” later published in The Realist, which described the Free Store as a radical social experiment.

The Diggers extended the “free” concept to various aspects of life, including food, housing, energy, and art. The tie-dye craze, for instance, originated at the Free Store when a woman named Luna introduced the technique to transform piles of donated white shirts into vibrant, free art. This exemplified the Digger approach: taking everyday items and transforming them into something valuable and freely accessible.

Free Food and Street Events: Theater in the Everyday

For Peter Berg, the Diggers’ free food program in Golden Gate Park was more than just charity; it was a theatrical demonstration of the principle that food should be free for everyone. He envisioned the free food distribution as a “demonstration of an attitude,” a way to “enact the destination” of a future world where basic needs were met without cost.

The Diggers’ free food service was not simply about handing out meals. It was meticulously staged. Food was served from milk cans within a large, twelve-foot orange frame, dubbed the “Free Frame of Reference.” This frame, deliberately positioned to face morning commuters, transformed the act of receiving free breakfast into a living tableau, a “deliberate painting” challenging capitalist norms.

The Diggers’ street events were their most elaborate form of “free art.” These pageants, often unannounced and blending seamlessly into the fabric of Haight-Ashbury life, involved the unwitting participation of the public. “The Birth of Haight and the Death of Money” was one such event, a multi-sensory spectacle that transformed Haight Street into a living theater.

This event featured a black-draped coffin filled with oversized coins, carried by animal-headed figures singing a parody of “Get Out of My Life, Woman.” Rooftop reflectors flashed sunlight, and penny whistles were distributed to the crowd, creating waves of sound and light. The entire street became a stage, blurring the lines between performer and audience, reality and spectacle.

To access Haight Street during “The Birth of Haight and the Death of Money,” participants had to break through newsprint banners painted in paisley designs, symbolizing a necessary destruction of conventional aesthetics to enter this new reality. Women in avant-garde silver lamé Levi’s outfits, provided by Levi Strauss, recited Lenore Kandel’s poems from rooftops, amplifying the theatricality and literary dimension of the event.

The Beat Poets and the Psychedelic Revolution

Peter Berg recognized the deep connection between the Beat poets of North Beach and the psychedelic counterculture emerging in Haight-Ashbury. The Beat poets, disillusioned with mainstream society, saw the Diggers and the “hippie” movement as the realization of their protest and their desire for an alternative way of life. Figures like Lenore Kandel, Richard Brautigan, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, and Allen Ginsberg embraced the Diggers, viewing them as the “children of their desires.”

Kirby Doyle’s essay, “The Birth of Digger Batman,” further solidified this connection. Billy Batman, owner of the Six Gallery, where Ginsberg’s “Howl” was first read, named his child “Digger,” symbolizing the Beat generation’s embrace of the new counterculture. Ken Kesey’s bus “Furthur,” often parked in the Panhandle, became another iconic symbol of this convergence.

LSD: The “Magic Wand” of Consciousness Change

Peter Berg considered LSD an indispensable catalyst for the psychedelic rebellion and the Diggers’ proactive approach to social change. He argued that without LSD, the counterculture might have remained a passive protest, lacking the “magical ingredient” needed to transform society. LSD, in Berg’s view, was the “magic wand” that empowered individuals to “turn reality upside down” and envision a different world.

Berg never disavowed LSD, even as the mainstream turned against it. He saw the Diggers themselves as “social LSD,” an agent of consciousness change. The Digger ethos – “Everything is free/Do Your own thing” – mirrored the transformative potential of LSD, challenging societal norms and empowering individuals to embrace their creativity and individuality. He believed that LSD gave people the “authority” to see themselves as artists and to imagine a world where “everything can be turned upside down AND BE BEAUTIFUL.”

The Human Be-In and the Diggers’ Role

At the Human Be-In in 1967, a pivotal event in the counterculture movement, the Diggers played a significant role: distributing 3,000 tabs of LSD. These were provided by Owsley Stanley, a legendary figure in LSD production, in a clandestine exchange that underscored the risky and underground nature of the psychedelic movement. This act demonstrated the Diggers’ commitment to facilitating consciousness expansion and their central role in the psychedelic revolution.

The Communications Company and Spreading the Word

The Diggers disseminated their ideas and announcements through broadsheets produced by the Communications Company (Comm/Co). Chester Anderson, a former Beat and rebel against his military family, and Claude Hayward from Ramparts magazine, founded Comm/Co as the “free printers” for the Diggers.

Comm/Co’s output included daily or occasional sheets with practical information (overdose hotlines, social assistance numbers), announcements for street events, poems, and political statements. After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Comm/Co produced a poignant sheet with a splash of red and the words, “Goodbye, brother Martin. Today is the first day in the rest of your life.” Gary Snyder’s politically charged poem, “A Curse on the Men in Washington,” initially rejected by the Oracle newspaper, found its first publication as a Comm/Co street sheet, highlighting the Diggers’ commitment to free expression and radical voices.

The Grateful Dead and Free Concerts in the Park

The Diggers forged a connection with the Grateful Dead, inviting them to play at free events in Golden Gate Park. Initially hesitant, the band, after persuasion from their manager Danny Rifkin, recognized the significance of these free concerts for building their fanbase and solidifying their place in the counterculture.

The Grateful Dead’s participation in Digger events, along with Janis Joplin and other musicians, became a hallmark of the Haight-Ashbury scene. These free concerts, often in the Panhandle, transformed the park into a communal space for music, freedom, and shared experience. Janis Joplin also performed at the Diggers’ “Free City Convention” at the Carousel Ballroom, a chaotic and vibrant event that blended music, art, and political theater.

The Invisible Circus at Glide Church: 72 Hours of Liberation

The Diggers, in collaboration with the Artists Liberation Front, conceived of “The Invisible Circus,” a massive 72-hour event at Glide Memorial Church. This ambitious undertaking aimed to create a “city-shaking event” that would manifest free creativity and social liberation, with a distinctly Digger overlay.

Lenore Kandel played a crucial role in securing Glide Church for the event, convincing church officials that it was their “sacred, spiritual obligation” to support the liberation of people. The church, undergoing a transition to serve minority groups and the poor under the leadership of Cecil Williams, surprisingly granted the Diggers complete freedom to use the space for the weekend.

Peter Berg and the Diggers transformed Glide Church into a multi-sensory, chaotic, and liberating space. One installation featured NASA footage of Earth abruptly interrupted by belly dancers. Berg himself organized an “obscenity panel” juxtaposed with a live “obscene” performance behind a glass wall. Lenore Kandel became a “foot reader” and transformed a bridal room into a “seduction room.” Emmett Grogan filled an elevator with shredded plastic. Richard Brautigan set up a “John Dillinger Computer” instant poetry publishing service. A pornographic film theater ran continuously.

The Invisible Circus became a magnet for a diverse crowd: poets, musicians, Hells Angels, military personnel, and Tenderloin residents. Despite the chaos and nudity, Berg described a moment of unexpected transcendence when a nude belly dancer was surrounded by respectful onlookers. The event, though eventually shut down by church authorities due to its intensity and perceived mess, was considered a resounding success by the Diggers and a significant moment in the counterculture.

SDS Meeting in Michigan: Taking the Digger Vision National

In 1966, Peter Berg and other Diggers attended a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) meeting in Denton, Michigan, aiming to present the Digger philosophy as a model for the New Left. Traveling in a rented station wagon, the trip became characteristically chaotic, culminating in a car accident and Billy Fritsch’s brief arrest.

Despite the mishaps, Berg, Emmett Grogan, and Billy Murcott arrived at the SDS conference. Berg, rejecting the more moderate Port Huron Statement of SDS, presented the Digger approach as a more radical and transformative alternative. Abbie Hoffman, present at the meeting, was inspired by the Diggers’ theatrical and anarchic style, declaring his intention to bring their methods to New York.

While Tom Hayden and other SDS leaders remained skeptical, the Diggers’ presence at the conference marked an attempt to influence the direction of the New Left and expand their vision beyond San Francisco. Todd Gitlin, in his book The Sixties, later jokingly claimed that Berg “personally destroyed SDS,” highlighting the Diggers’ disruptive and unconventional approach to political activism.

The Alan Burke Show: Guerrilla Television

Seeking to expand their reach, Peter Berg accepted an invitation to appear on The Alan Burke Show, a confrontational television program known for its shock-jock style. Berg saw this as an opportunity to subvert the coercive nature of television and spread the Digger message to a wider audience.

Bringing an antique pistol as a prop and arranging for Natural Suzanne to throw a pie, Berg approached the show as another form of guerrilla theater. Ignoring Burke, Berg addressed the audience directly, engaging in repartee and disrupting the show’s format. When a woman in the audience challenged the Diggers’ demands for freedom, Berg introduced “Emma Goldman” (Natural Suzanne), who promptly threw a pie in the woman’s face, shocking the audience and Burke.

Berg then turned to the camera, instructing the cameraman to pan up to show the studio lights and girders, exposing the artificiality of television. He announced his departure, urging viewers to turn off their television sets as he walked off the set. Berg’s appearance on The Alan Burke Show became a legendary example of guerrilla television, a successful disruption of mainstream media and a powerful assertion of Digger autonomy.

The Hells Angels and “Heavy Hippies”

The Diggers’ relationship with the Hells Angels was complex and multifaceted. While some Digger women had romantic relationships with Angels, Peter Berg viewed the connection in terms of power and street credibility. The Diggers, identifying as “heavy hippies,” sought to be seen as more than just “flower children,” capable of direct action and confrontation.

Berg recognized the need for the Diggers to be “heavier” in order to challenge authority effectively. The Diggers deliberately provoked the police, staging street events designed to be arrested, and successfully defended themselves in court, gaining further notoriety and solidifying their image as radical actors.

Ultimately, Berg argued, it was police repression, not internal failings, that led to the decline of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture. He described the militarization of Haight Street – mercury vapor lights, one-way traffic, constant paddy wagon patrols – as deliberate tactics to “close down the Haight-Ashbury” and reclaim control of the neighborhood that the Diggers had, in effect, “taken over.”

“1% Free”: Provoking the Mainstream

The Diggers’ “1% Free” slogan encapsulated their understanding of their role in society. Peter Berg explained that “Only one percent of the population can bring this off, at this time. Only one percent of the people are capable of acting out the Digger vision.” The slogan was intended to be provocative, to challenge the “rest of the population” to join the Diggers in their radical social experiment, until the “one percent” became “a hundred percent.”

The “1% Free” image, inspired by a photo of Chinese Tong men, was deliberately ambiguous and confrontational. When the Diggers posted the image in Chinatown, someone added a balloon saying, “White guys are only 1% free. Chinese are 101% free,” highlighting the slogan’s open-ended and provocative nature. This slogan, like the Diggers’ actions, aimed to challenge conventional thinking and inspire a broader social transformation.

Peter Berg’s Lasting Vision

Peter Berg’s work with the Diggers and his subsequent contributions to bioregionalism through Planet Drum, the foundation he co-founded with Judy Goldhaft, demonstrate a lifelong commitment to radical social and environmental change. His concept of “life acting,” guerrilla theater, and the Diggers’ “free” philosophy continue to resonate as powerful critiques of consumerism, authority, and conventional ways of life. Peter Berg’s legacy as a visionary thinker and activist remains relevant, inspiring ongoing explorations of alternative social models and creative resistance.

This in-depth look at Peter Berg, based on his own words, provides a valuable window into the counterculture of the 1960s and the enduring relevance of his ideas for contemporary social and environmental movements. His emphasis on direct action, creative expression, and the power of “free” continues to challenge and inspire those seeking a more just and sustainable world.