Plastic waste is a pressing global issue, and the environmental impact of improper disposal is widely recognized. Among plastics, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a significant contributor to packaging waste, especially in the beverage industry. In the US alone, PET bottles comprised 44.7% of single-serve beverage packaging in 2021, and globally, they account for 12% of solid waste. To address this, strategic and effective solutions for managing plastic packaging waste are crucial. Leading beverage manufacturers are increasingly committed to sustainability, seeking to minimize their environmental footprint. Pet Bottle Recycling offers a promising path towards achieving these goals.

PET bottles possess inherent qualities that make them an environmentally sound choice, particularly for recycling. Their mono-material composition simplifies the recycling process, and they boast excellent barrier properties to protect beverages. Compared to heavier alternatives like glass, PET bottles are lightweight, resulting in a reduced carbon footprint during both production and transportation. Furthermore, advancements in decontamination technologies for post-consumer recycled PET (rPET or PCR) have made it a safe material for reuse in beverage packaging. For three decades, the FDA has certified PCR PET production processes as safe for food contact applications within the United States, solidifying its viability.

This comprehensive guide delves into the world of pet bottle recycling, providing an in-depth look at bottle-to-bottle recycling and offering valuable insights for beverage manufacturers aiming to enhance their sustainability initiatives.

1. Understanding PET and Beverage Packaging

Plastic packaging dominates the consumer product market, accounting for a significant 70% share. Beverage packaging itself can be broadly categorized by filling method: cold fill (aseptic), carbonated soft drinks, and hot fill. Selecting the right packaging material is a critical decision, demanding consideration of several factors. The material must withstand diverse temperatures during filling and handling, preserve beverage quality throughout its shelf life, and endure internal pressure when required. Thermal stability requirements are dictated by the sterilization process of the beverage and its container. Cold-fill beverages, such as water and high-acid drinks, do not necessitate sterilization. Hot-fill beverages, including high-acid and acidified products like isotonic drinks, teas, and juices, require heat resistance. Carbonated beverages, such as sodas, demand packaging that can withstand internal pressures up to 5 bar at room temperature without deformation.

The choice of packaging material significantly impacts beverage preservation, preventing degradation, maintaining organoleptic qualities (smell, taste, texture), and nutritional value (e.g., preventing vitamin C oxidation in juice), and ensuring consumer health and safety. A range of materials are suitable for beverage packaging based on barrier and mechanical properties, including glass bottles, aluminum cans, foil-laminated carton boxes, flexible pouches, and plastic bottles 1, 2.

Among plastic options, polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE), a polyester plastic, stands out as a prevalent choice for beverage packaging. Its popularity stems from its exceptional clarity, lightweight nature, barrier properties against gas and water, impact resistance, UV resistance, and durability compared to glass. Consequently, the production and use of PET bottles for beverage packaging have consistently grown globally. PET presents a recyclable and high-performing solution unmatched by alternative packaging materials such as glass, aluminum, paperboard, and other plastics. Industry data from Euromonitor International reveals that PET bottles hold a dominant 67% market share in the beverage sector, encompassing water, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, tea, and coffee. Specifically, for single-serve bottles (under 1 liter), PET accounted for 44.7% of the US market in 2021, surpassing aluminum cans (39%), glass (11%), and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) (3.4%).

However, like most plastics, PET is derived from petroleum, a fossil fuel. It exhibits slow degradation when discarded as waste, contributing to environmental pollution. In 2015, global plastic waste generation reached approximately 141 million tons 3. Plastic packaging in landfills contributes to air, water, and soil pollution, and consumes valuable landfill space. Critically, plastic occupies a larger volume in landfills compared to its weight 4. Incinerating plastic waste offers landfill space savings and energy generation but raises concerns about emissions and air pollution. The infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch vividly illustrates the problem of plastic waste accumulation in unwanted environments. Plastic waste pollution is now widely recognized as a major global environmental challenge.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the United States generated 35.7 million tons of plastic waste in 2018, representing 12.2% of total municipal solid waste (MSW). This figure includes PET bottles, polyolefin, and polyester bags, wraps, bottles, and jars. Alarmingly, approximately 27 million tons of plastic (18.5% of US plastic waste) ended up in landfills, with only 4.5% of plastic packaging being recycled 5. Data from the European Economic Area for the EU in 2019 shows an average plastic packaging waste generation of 34.4 kg per EU resident. The EU achieved a recycling rate of 41% (14.1 kg) per inhabitant 6. Globally, PET constitutes 12% of total solid waste. The EU Commission for the Environment has proposed strategies for member countries to significantly decrease plastic waste leakage, focusing on incentivizing consumer behavior change, improving waste management through enhanced collection, separation, and recycling, and restricting landfill waste acceptance 7.

Source reduction, or waste prevention, is defined by the EPA as altering the design, manufacturing, purchasing, or usage of materials or products (including packaging) to reduce their quantity or toxicity before they become municipal solid waste 8. To effectively manage plastic waste, source reduction can be implemented using waste management principles like reuse, reduce, redesign, and recycle, combined with packaging innovation. Many regions, including North America, Europe, and South Asia, have promoted recycling programs and/or implemented packaging waste management policies, including deposit systems, taxes, and plastic bag bans.

Bottle reuse through returnable bottle systems is common practice in South America and several European nations 9, 10, 11, effectively reducing waste. However, in many regions, PET bottles are designed for single-use and discarded after their initial purpose. To mitigate the environmental impact of packaging waste and promote sustainability in plastic packaging, municipal recycling programs have been established to capture recyclable material streams. The incorporation of recycled plastics in food contact packaging has been slow due to food safety concerns. However, growing public pressure and increased manufacturer adoption are gradually shifting this perception 12.

Post-consumer recycled (PCR) material can indeed serve as primary packaging for food contact applications. Consequently, the collection and recycling of PET bottles into PCR are steadily increasing. PET recycling technology has undergone significant development and widespread implementation for over five decades 13, 14, 15. These advancements continue with improved methods for recovery and conversion into PCR pellets. Moreover, bottle-to-bottle recycling initiatives divert PCR pellets from less demanding applications. Considering bottle-to-bottle recycling alongside other applications like strapping, textiles, and injection molding, PET has emerged as one of the most successfully recycled plastic materials.

While PET packaging waste recycling processes have become increasingly sophisticated, detailed knowledge of the unit operations involved often remains confined to recyclers. Beverage manufacturers express valid concerns regarding the food contact safety of PCR produced from PET containers that may have previously held chemicals or household products. Hazardous compounds potentially absorbed by the PET polymer could migrate into food if not adequately removed during recycling 16. However, established methods like managed waste collection, super clean processes, and advanced recycling offer pathways to produce PCR PET with effective chemical contamination removal. These processes hold the potential to yield PCR PET with contaminant levels comparable to virgin PET 17.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive framework for beverage manufacturers to make informed decisions about incorporating PCR PET options for their products. It delves into the essential aspects of pet bottle recycling, including processes, applications, food safety, regulations, and future trends, to assist manufacturers in advancing their sustainability objectives.

2. PET Recycling Processes: Recovering Value from Waste

PET, or polyethylene terephthalate, is a thermoplastic polyester created through a condensation reaction between ethylene glycol (EG) and terephthalic acid (TPA), also known as purified terephthalic acid (PTA). Figure 1 (below) illustrates this chemical reaction.

Figure 1. Chemical reaction of terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol forming polyethylene terephthalate.

Both EG and TPA are typically derived from petroleum. PET can also be produced via transesterification of dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) with EG to form bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET), followed by BHET reaction with the growing PET chain, releasing EG.

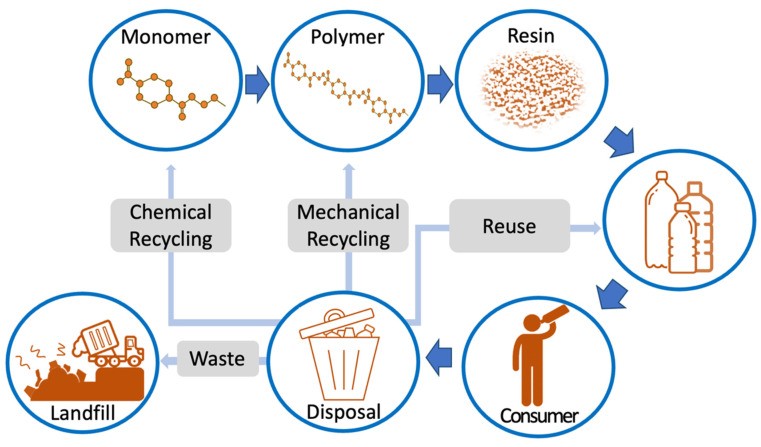

Due to the condensation reaction, PET’s main chain includes non-carbon atoms. The benzene component in the main chain contributes to the polymer’s stiffness. PET can exist in both amorphous and semi-crystalline forms depending on processing and thermal treatment 18. Thermal processing also generates BHET and low-molecular-weight polymers (oligomers). PET’s glass transition temperature (Tg) ranges from 67 °C (amorphous PET) to 81 °C (crystalline PET), with a melting point around 256–260 °C 19. The most common method for PET bottle production is two-step injection stretch blow molding (ISBM). Bottles are filled and distributed to consumers. After consumption, discarded bottles enter various recycling streams. Figure 2 (below) provides a simplified overview of the PET bottle lifecycle.

Figure 2. Plastic packaging life cycle of a PET bottle.

2.1. Efficient Collection Systems for PET Bottles

Proper disposal and collection are fundamental to effective pet bottle recycling. Source separation, aimed at isolating recyclable plastics before they contaminate landfill waste, minimizes contamination and improves recovery efficiency. Post-consumer PET beverage bottle collection primarily relies on two systems: curbside collection and deposit systems.

Curbside collection involves segregating PET bottles from other recyclables at Materials Recovery Facilities (MRFs). MRF designs vary based on local collection models, which broadly fall into four categories 20:

- Complete Citizen Separation: Consumers separate waste at home into categories like paper, glass, metal, and plastic, each collected separately.

- Truck Sorting: Collection drivers sort materials into categories during curbside pickup, reducing MRF sorting needs.

- Site Separation: All sorting occurs at the MRF, using manual or mechanical methods.

- Co-collection: No separation occurs at collection, mixing trash and recyclables, creating significant MRF separation challenges and higher costs.

Deposit systems, governed by deposit-return legislation or bottle bills, use financial incentives to boost recycling rates. A deposit fee is added to beverage containers at purchase, refunded to consumers upon returning the empty container to a collection center. Container deposit legislation (CDL) promotes mono-material collection streams and higher quality PCR PET. In the US, ten states have deposit laws. States with bottle bills achieve approximately 60% beverage container recycling rates, significantly higher than the 24% in non-deposit states 21. Economic studies show a direct correlation between deposit fee amount and container return rates 22. Bottle bills effectively increase beverage container recycling and influence consumer behavior. However, political resistance and beverage industry opposition hinder deposit system enactment in some US states 23. Collection methods critically impact contaminant reduction and recycled PET quality 24, 25. Curbside and deposit collection programs have partial overlap. Curbside programs cover household recyclables not in deposit programs, while deposit programs recover containers from locations curbside may miss. The overarching goal is to minimize solid waste and maximize recyclable material recovery.

2.2. PET Value Recovery Methods: From Waste to Resource

Recycling technology offers a valuable alternative to landfill disposal. PET value recovery is achieved through four primary methods: primary (re-extrusion), secondary (mechanical), tertiary (chemical), and quaternary (energy recovery) 26, 27, 28. Each method presents distinct advantages and disadvantages regarding cost, quality, and environmental impact.

2.2.1. Primary Recycling: Re-extrusion for In-Plant Waste

Re-extrusion is a recovery process used by plastic packaging manufacturers to reclaim in-plant waste. Uncontaminated scrap is shredded into flakes and either mixed with virgin material or used as a second-grade material for alternative molding applications 29. Post-industrial recycled (PIR) materials are distinct from PCR because they never reach consumers before recovery 30.

2.2.2. Secondary Recycling: Mechanical Recycling for Broad Application

Mechanical recycling is a conventional and widely used pet bottle recycling method. Plastic containers are sorted, contaminants removed, washed, dried, ground into flakes, melted, and reprocessed into plastic pellets through extrusion. This process is physical and does not alter the polymer’s chemical structure. However, it can impact the molecular weight of the recycled PET 31. PET is hydrophilic and absorbs moisture. At high temperatures during melt extrusion, reaction with water leads to hydrolytic degradation (hydrolysis), reducing average molecular weight (MW). Lower MW negatively affects mechanical properties, melt viscosity, and impact resistance 32. To counter this, PCR manufacturers often increase PET molecular weight using solid-state polymerization (SSP). The polymer is heated below its melting point but above its glass transition temperature in an inert environment, removing condensate byproducts and yielding higher MW polymer. SSP improves intrinsic viscosity (IV) and eliminates volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Post-SSP, recycled PET can be analyzed for benzene and limonene content. Benzene indicates PVC contamination and degradation, while limonene, from citrus juice residues, can affect beverage organoleptic properties 28. Quantifying these VOCs verifies SSP effectiveness and PCR suitability for food contact. Mechanical recycling of PET is widely adopted globally 33.

2.2.3. Tertiary Recycling: Chemical Recycling for High Purity

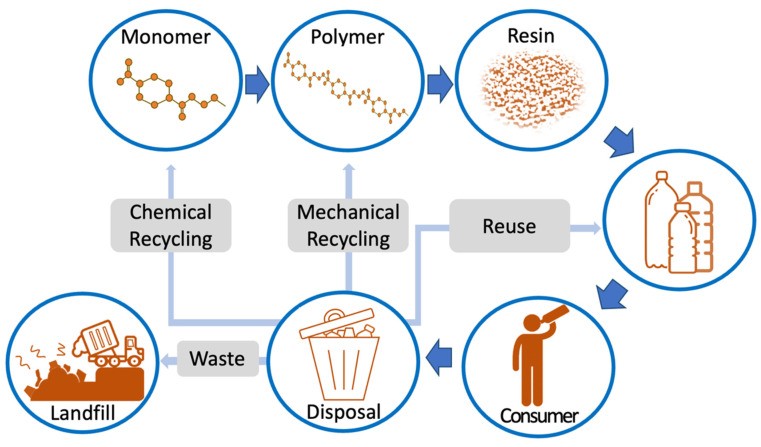

Chemical recycling, also known as advanced recycling, involves depolymerizing PET back to its original components or solvating it for purification 34. The polymer chain is broken down into smaller oligomers or monomers, liquids, and gases 35. Monomers can be refined using processes unsuitable for long-chain polymers. Chemical recycling is ideal for mixed or contaminated plastics and requires minimal pretreatment. Breaking down the material allows for finer filtration and superior purification compared to mechanical recycling. This method is applicable to PET and other polymers like polyamides, polyurethanes, and polyethylene 30. Chemical recycling of PET is an active research area 36, 37. Five main chemical recycling methods exist for PET: methanolysis, glycolysis, hydrolysis, ammonolysis, and aminolysis. However, methanolysis and glycolysis are the most commercially relevant 38. Figure 3 (below) summarizes different PET chemical recycling methods and their products.

Figure 3. Chemical recycling methods for PET.

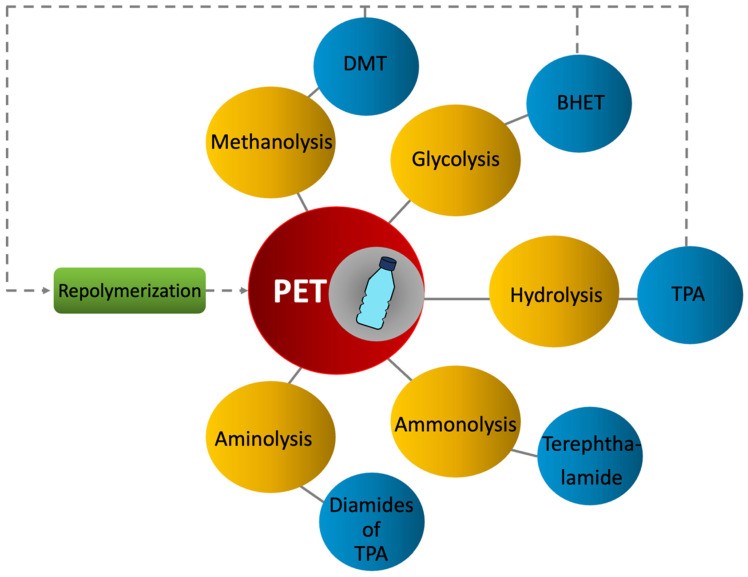

Methanolysis: Depolymerization with Methanol

Methanolysis depolymerizes PET into DMT and EG using methanol at high pressure (2–4 MPa) and temperature (180–280 °C) 39, 40. DMT can be repolymerized into PET via two pathways: (1) transesterification of DMT with EG to form BHET, followed by BHET reaction with the PET chain; or (2) DMT hydrolysis to TPA and methanol, followed by TPA and EG reaction. Catalysts like zinc acetate, magnesium acetate, lead dioxide, and cobalt acetate are used, with zinc acetate being most common 41, 42. Reaction products may include alcohols, glycols, and phthalate derivatives 43. DMT yield typically ranges from 80–85%. Figure 4 (below) shows the methanolysis reaction.

Figure 4. Chemical reaction for methanolysis.

Research explores aluminum isopropoxide catalyst with toluene and methanol for improved monomer yields 44. Catalyst removal is crucial post-reaction to prevent polymer degradation and DMT loss. DMT is separated by centrifugation and crystallization. Both batch and continuous processes are applicable 38, 40.

Supercritical methanol can also depolymerize PET at 270–300 °C and 0.1–15 MPa. High-MW PET decomposes faster than low-MW PET 45. DMT purification is easier than BHET from glycolysis. Methanolysis is preferred for low-quality feedstock not competing with mechanical recycling. However, it is more costly and energy-intensive than glycolysis 46, 47.

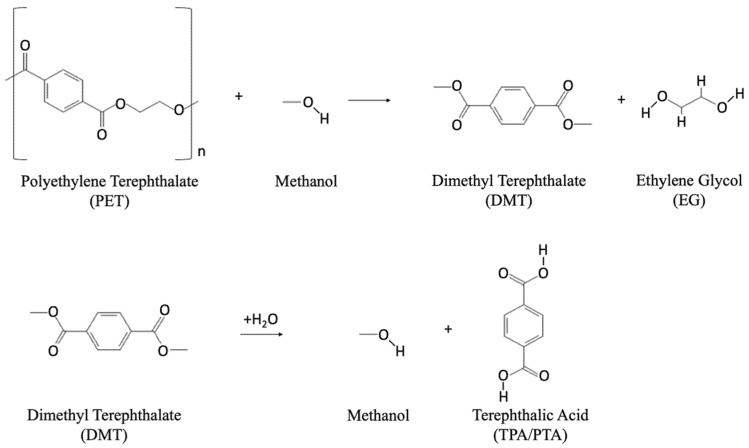

Glycolysis: Economical Depolymerization with Glycol

Glycolysis is the most economically viable and commercially favored chemical recycling method for pet bottle recycling. It is primarily used for high-quality PET bottles and can compete with mechanical recycling for feedstock. Ethylene glycol (EG) breaks ester linkages in the PET chain, producing BHET, as shown in Figure 5 (below).

Figure 5. Glycolysis chemical reaction of PET with ethylene glycol to produce BHET.

The reaction occurs under pressure at 180–240 °C 28, 38, often in an extruder 47. Catalysts enhance BHET production rate. Research focuses on efficient catalysts, optimized reaction conditions (time, temperature, PET/EG ratio), and catalyst concentration to maximize reaction rate and BHET yield 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55.

Four main glycolysis methods exist: catalyzed, solvent-assisted, supercritical, and microwave-assisted 56.

-

Catalyzed Glycolysis: Zinc catalysts generally outperform transition metal catalysts. Zinc salts are catalytically active below 245 °C 57. Zinc acetate yields the highest BHET recovery compared to other metal acetates 42, 58. Manganese acetate catalyzes optimally at 190 °C for 1.5 h with 0.025 moles per kg PET 59. Metal chloride catalysts like zinc, lithium, didymium, magnesium, and iron perform similarly to acetate salts. Zinc chloride (0.5 wt%, PET:EG 1:14) achieved 73.24% BHET yield in 8 hours 60. Mild alkalis like sodium carbonate and bicarbonate are environmentally friendlier catalysts 61, yielding BHET comparable to zinc and lead acetate. Other eco-friendly catalysts like glacial acetic acid, lithium hydroxide, sodium sulfate, and potassium sulfate also show comparable yields 62. Titanium-phosphate catalyst at 200 °C for 2.5 h achieves 97.5% BHET recovery, exceeding zinc acetate’s 62.8% 63. Solid catalysts like SO42−/ZnO, SO42−/TiO2, and SO42−/ZnO-TiO2 are thermostable, superacidic, and highly active. SO42−/ZnO-TiO2 achieves 100% PET conversion with 72% BHET selectivity in 3 hours at 180 °C. Solid catalysts are easily removed by filtration and are non-corrosive, but require high temperatures and pressures 52. Reusable catalysts like nanocomposites and ionic liquids are being developed. Metal oxides at nanoscale are promising catalysts due to surface area and active sites 65, 66, 67, 68, 69. Polyoxometalates (POMs) are inorganic metal-oxygen clusters used in various catalytic reactions 70, 71, 72. Transition-metal-substituted POMs show high catalytic activity, with SiW11Zn achieving over 84% BHET yield in 30 min under mild conditions 73. Ionic liquids, like 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide ([bmim] Br), achieve 100% PET conversion in 8 hours at atmospheric pressure and 180 °C and can be reused 56, 74, 75, 76.

-

Solvent-Assisted Glycolysis: Organic solvents like xylene enhance zinc acetate catalyst activity, achieving 80% BHET yield by improving PET-glycol miscibility 77. However, large-scale organic solvent use is environmentally undesirable 48.

-

Supercritical Glycolysis: Supercritical EG conditions (450 °C and 15.3 MPa) achieve 93.5% BHET yield within 30 min 78 due to high solvent density, solubility, and reaction kinetics. No catalyst is needed, simplifying product separation, but energy demand is high 79.

-

Microwave-assisted Glycolysis: Microwave radiation reduces reaction time from 8 hours to 35 min 80. Alkali catalysts with microwave radiation reduce reaction time to under 3 min 81. Zinc acetate catalyst (0.5%, w/w) in microwave-assisted glycolysis minimizes reaction time to 30 min 82. Ionic liquid catalysts with microwave radiation at 170–175 °C yield 64% BHET with up to 100% PET conversion 83. A second glycolysis step can further depolymerize residual oligomers to maximize yield.

Hydrolysis: Depolymerization with Water

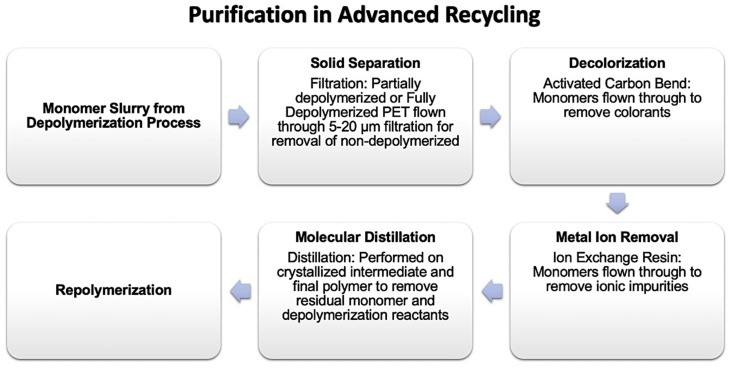

Hydrolysis depolymerizes PET into EG and TPA using water. It’s less common for food-grade recycled PET due to costly TPA purification. It’s conducted at high pressure (1.4–2 MPa) and temperature (200–250 °C) under acidic, basic, or neutral conditions. Three main hydrolysis methods exist:

Acid Hydrolysis:

Figure 6. Chemical reaction for acid hydrolysis process.

Concentrated acids like sulfuric acid (H2SO4) at 220–270 °C yield TPA and EG 84, 85, 86. Longer reaction times and high temperatures are needed with lower H2SO4 concentrations 87. EG is recovered via organic solvent extraction. Acid hydrolysis is expensive and generates large amounts of inorganic salts and aqueous waste due to corrosive chemicals.

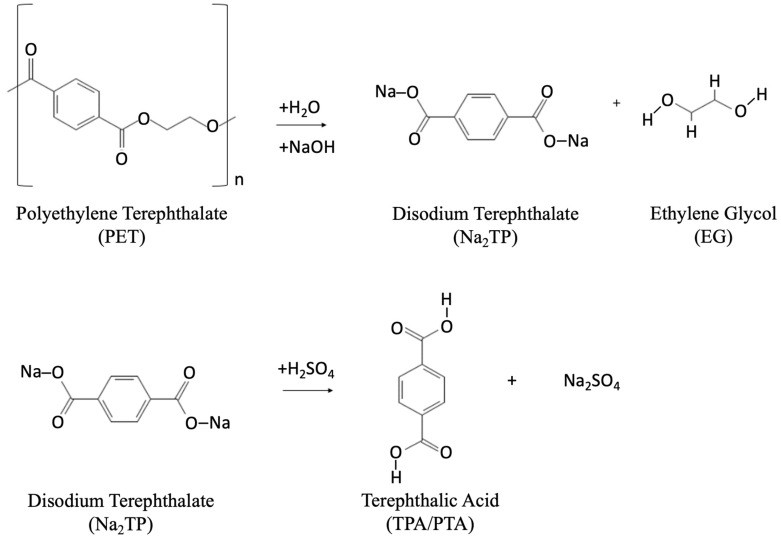

Alkaline Hydrolysis:

Figure 7. Alkaline hydrolysis chemical reaction to produce TPA.

Alkaline hydrolysis uses bases like sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at 90–200 °C 88, 89. It is commercially viable, handles contamination well, and produces high-quality TPA. TPA yield depends on temperature and catalyst concentration 89. Aqueous ammonia solution at 200 °C also shows good results 90. Phosphonium quaternary salts increase alkaline hydrolysis reaction rate significantly at lower temperatures 54.

Neutral Hydrolysis:

Figure 8. Chemical reaction during neutral hydrolysis process.

Neutral hydrolysis uses water under high pressure and temperature (250–300 °C) 91, 92. EG recovery up to 60% has been shown at 300 °C. Diluted EG is recovered by extraction or distillation. Neutral hydrolysis is more environmentally friendly than acid/alkaline hydrolysis due to less salt formation. However, TPA purity is lower, requiring filtration of TPA solution in caprolactam or sodium hydroxide 93. Crystallization from caprolactam yields TPA with over 99% purity 94.

Ammonolysis: Depolymerization with Ammonia

Ammonolysis depolymerizes PET with anhydrous ammonia (NH3) and EG to produce terephthalamide (Figure 9 below).

Figure 9. Chemical reaction during ammonolysis process to produce terephthalamide.

Terephthalamide can be converted to terephthalonitrile, para-xylylene diamine, and 1,4-bis(aminomethyl)- cyclohexane 95. Reaction conditions are 120–180 °C and 2 MPa for 1–7 hours for post-consumer PET bottles 38, 96. Terephthalamide purity exceeds 99% with over 90% yield 95. Low-pressure ammonolysis with zinc acetate catalyst (0.05 wt%) at 70 °C achieves 87% TPA amide yield 38.

Aminolysis: Depolymerization with Amines

Aminolysis of PET produces diamides of TPA and EG. It’s less commercially used for pet bottle recycling, but more for improving PET fiber properties 97. Aqueous amine solutions like methylamine, ethylamine (Figure 10 below), and ethanolamine are used at 20–100 °C 97, 98, 99, 100, 101.

Figure 10. Aminolysis process chemical reaction for depolymerization of PET.

Other amines include butylamine, triethylenetetramine, allylamine, polyamines, morpholine, and hydrazine 102, 103, 104, 105. Ethanolamine with catalysts like glacial acetic acid yields 91% pure bis(2-hydroxy ethylene) terephthalamide (BHETA) 106. Microwave-assisted aminolysis with ethanolamine yields nearly 90% BHET in 4 minutes 80.

Combining chemical recycling processes enhances depolymerization and contamination removal 107, such as glycolysis-hydrolysis, methanolysis-hydrolysis, glycolysis-methanolysis, and glycolysis-aminolysis. High purity rPET from chemical recycling is highly attractive for commercial applications, reducing resource consumption and environmental impact 48. Chemical recycling can be expensive, potentially requiring regulations like carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions penalties to promote adoption 108.

2.2.4. Quaternary Recycling: Energy Recovery from Incineration

Quaternary recycling recovers energy from plastic waste by incineration, converting chemical energy to thermal energy. It’s suitable when other methods are impractical due to heavy contamination. Incineration converts waste to carbon dioxide and water, with energy used for electricity generation. Residuals are landfilled 28. Incineration emissions are regulated in the US by the Clean Air Act 109, with EPA and state collaboration to meet Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) standards.

3. Recycling Operations for PCR PET: Ensuring Quality and Safety

3.1. Advanced Sortation and Purification Techniques

Virgin PET is engineered for specific purposes, with grades tailored for intrinsic viscosity and crystallization rate based on applications like water, hot fill, or carbonated drinks. Virgin material properties are controlled through comonomer selection, content, and catalyst systems. Additives enhance performance, including reheat additives, toners, colorants, and oxygen barriers.

The pet bottle recycling stream initially contains PET containers, closures, labels, and consumer product residues. Contamination risks include HDPE and PP from closures, adhesives, PETG, paper, and PVC from labels. Product residues and non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) can also enter during reclamation.

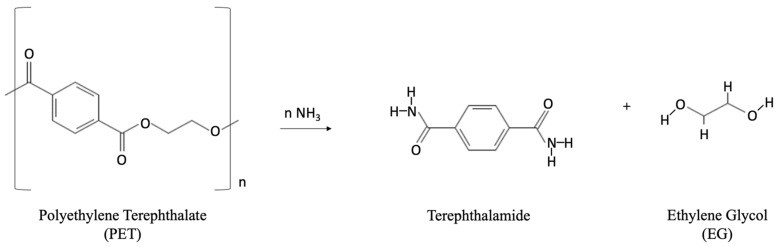

Mechanically recycled rPET contains some contaminants from the recycle stream. Sortation unit operations, shown in Figure 11 (below) A and B, reduce contamination. These include near-infrared (NIR) material identification, color recognition, eddy-current separation, float/sink density separation, and elutriation for label removal. Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly used in sortation, employing deep learning and vision systems to identify and remove non-PET containers.

Figure 11. Unit operations in recycler: (A) container sortation and (B) flake sortation.

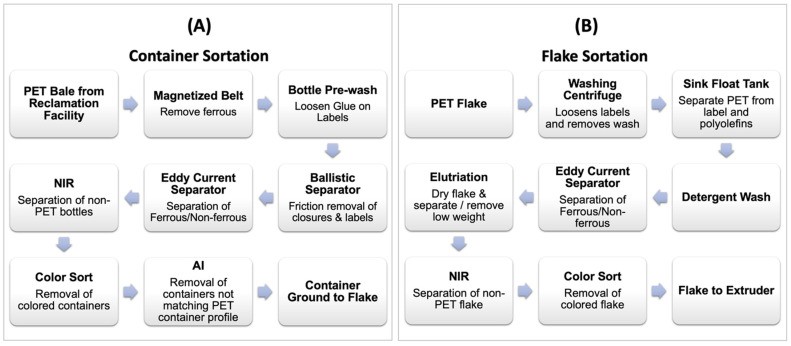

Advanced or chemical recycling breaks down PET into smaller molecules or monomers, as depicted in Figure 12 (below), effectively removing non-PET contamination. Repolymerized PET crystallization rate and IV can be tailored. Managing chemical recycling residuals, especially DEG, is important as they can affect copolymer composition and PET flexibility.

Figure 12. Unit operations in advanced recycling purification.

IV in mechanically recycled PET is controlled via polycondensation reactions. Two main approaches are: (1) enhancing IV on incoming flake and (2) enhancing IV in outgoing pellets. Both involve holding PET in inert environments at 190–210 °C. Flake IV enhancement (e.g., Erema® systems, chain extenders, solid-phase reactor polycondensation) simultaneously dries flake, reducing hydrolysis and IV loss. SSP on pellets outside the extruder removes volatiles present before and generated during extrusion, such as acetaldehyde and ethylene glycol, minimizing 2-methyl-1,3-dioxolane 110.

Mechanical recycling with repolymerization can produce fit-for-purpose IV. Contamination in mechanically recycled rPET depends on sortation efficiency. Even with efficient non-additive removal, rPET will contain a blend of comonomers, catalysts, toners, colorants, and additives from the input stream.

3.2. Super Cleaning Process for Food-Grade PCR PET

Non-food contamination poses consumer safety risks 25. Non-food PET bottles can contaminate rPET. Super-clean recycling, or deep-clean recycling, enhances decontamination for food contact reuse. It involves three stages: (1) high-temperature wash, (2) gas wash, and (3) chemical wash 16, 111, utilizing high-temperature washing, vacuum, surface treatment, melt filtration, and degassing 112. Flake washing uses chemicals like caustic soda and ethylene glycol to accelerate contaminant removal. SSP also removes contaminants. Heating PET to 200 °C brings contaminants to the surface, followed by vacuum or inert gas treatment to remove them from the recyclate stream.

Cleaning efficiency depends on non-food bottle quantity in the feed stream. Super-clean bottle-to-bottle recycling was pioneered in Beaune, France 16, followed by plants in the US, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, and Australia 113, 114.

4. Processing and Performance Differences: Virgin vs. PCR PET

PCR PET exhibits processing and performance differences compared to virgin PET. Container manufacturing with PCR requires expertise beyond simple material substitution. Virgin PET processing is typically consistent. However, PCR from different lots, even from the same supplier, can behave variably due to batch-to-batch raw material variations. Virgin PET for beverage containers falls into three categories:

- Water Grade: Low IV, acetaldehyde suppression, potential additives for thin walls.

- Heat-Set Grade: Higher IV, DEG suppression, comonomers for hot-fill shrinkage resistance, potential additives for reheating and crystallization.

- Carbonated Soft Drink (CSD) Grade: Highest IV, comonomers for expansion resistance.

Recycled bottles contain varying proportions of these virgin grades. PCR PET pellets can have diverse comonomers, additives, and additive levels. Color variability also arises from impurities and feedstock colors. PCR manufacturers minimize these variations, but converters must adapt. Variability is influenced by seasonality and bottle bale source. PCR material property variations impact preform injection and blow molding stability, and can affect consumer sensory experience. The bottle manufacturing process itself impacts final PCR PET bottle quality.

4.1. Injection Molding Considerations with PCR PET

4.1.1. Material Drying and Injection Pressure Adjustments

PET drying is crucial to prevent IV loss. PCR absorbs moisture faster than virgin PET, potentially due to lower crystallinity. Lower crystallinity facilitates moisture penetration. PCR pellet shells can be less crystalline than cores. During injection, crystalline shells melt, but cores may not. Screw recovery and barrel temperature profiles require adjustments to prevent gumming. Vinyl ester end groups in PCR can cause yellowing or browning during drying 115, necessitating lower drying temperatures and longer durations, impacting productivity. Balancing drying conditions for PCR and virgin PET blends is challenging, requiring compromise to ensure both materials are adequately dried without degradation, even with PCR lot variations.

4.1.2. Acetaldehyde (AA) Generation Control

Acetaldehyde (AA), a PET processing byproduct and natural flavoring compound, is particularly problematic in unflavored water. PCR lot-to-lot variability can affect AA generation risk. While less critical for hot-fill or sweetened carbonated drinks, it’s crucial for water bottle preform injection.

4.1.3. Haze Management due to Nucleation Sites

PCR preforms can exhibit haze due to increased nucleation sites and readily crystallizing smaller chains. Increasing cooling time in injection cycles can reduce haze, but at the cost of reduced productivity, increased degradation, higher AA levels, and increased cost, potentially adding 10-30% to cycle time.

4.1.4. Intrinsic Viscosity (IV) Degradation Mitigation

Intrinsic Viscosity (IV) indicates molecular chain length and material strength. Virgin resins typically experience minimal IV loss (≤0.03 dL/g) during injection molding under normal conditions. PCR IV loss can be less predictable due to residual compounds affecting stability in high-heat, high-shear extrusion environments. Residual reactants and catalysts from chemical recycling, if not fully removed, can cause depolymerization during injection, leading to significant IV drop. Degradation sensitivity varies by PCR batch.

4.2. Preform and Container Appearance Variations

PCR color varies significantly between lots and manufacturers. Figure 13 (below) illustrates color variation across PCR grades.

Figure 13. PCR resin color variation (image courtesy of Amcor).

Pellet crystallinity gives a white appearance, not indicative of transparent article color. Figure 14 (below) shows preforms from 100% PCR from different manufacturers, demonstrating significant appearance variation.

Figure 14. PCR preform color variation (image courtesy of Amcor).

Color differences are more pronounced in preforms due to thicker walls compared to final bottles. Bottle transparency increases and color density decreases with wall thickness reduction. Color visibility is highest in the bottle finish where thickness is maintained, as shown in Figure 15 (below).

Figure 15. PCR preforms and bottles (image courtesy of Amcor).

Table 1 (below) shows bottle mid-section color and haze measurements. Lightness (L* value) is similar to virgin containers, but green-red (a*) and blue-yellow (b*) dimensions are closer. Haze and yellowness index differences are more significant.

Table 1. Color and haze of PET bottles with different PCR grades.

| PET Type | L* | a* | b* | % Haze | Yellowness Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin | 94.61 | −0.04 | 0.60 | 0.74 | 1.13 |

| PCR Grade A | 94.83 | −0.10 | 0.77 | 2.34 | 1.39 |

| PCR Grade B | 94.88 | −0.14 | 1.32 | 1.92 | 2.42 |

| PCR Grade C | 93.19 | −0.17 | 2.64 | 6.20 | 4.99 |

| PCR Grade D | 94.65 | −0.14 | 0.82 | 2.59 | 1.47 |

4.3. Blow Molding Process Adaptations for PCR PET

4.3.1. Preform Heating and Energy Efficiency

Blow molding requires heating preforms above PET’s glass transition temperature using near-infrared (IR) radiation. Preform color affects IR absorption efficiency. PCR processing differs significantly from virgin PET due to composition variability. Reheat additive levels vary by PCR batch and source. PCR from regions without reheat additives requires more heating energy. US PCR may have varying reheat additive levels depending on the mix of water, CSD, and heat-set bottles recycled. Cleaner-looking PCR often requires more heating energy in blow molding than darker PCR, unless reheat additives are added.

Darker PCR can lead to gate swing or off-centered gates, causing uneven bottle wall thickness. Lot-to-lot preform color variations impact IR absorption and material distribution. Blow molding parameters may require adjustments for each production run. Experienced operators can adapt processes as needed.

4.3.2. Material Distribution Variability

Material distribution, or weight variation in the vertical direction, is crucial for performance in hot-fill and CSD bottles. PCR composition and color changes necessitate recipe adjustments. Wider molecular weight distribution in PCR can lead to more variable material stretch compared to virgin PET, resulting in less consistent material distribution within the bottle body.

4.3.3. Scrap Rate Increase Considerations

Inclusions in PCR PET can cause container ruptures during blow molding. Material distribution variations can lead to rejections. Scrap rates with PCR PET are generally higher than with virgin material, depending on PCR grade, lot, PCR percentage, and container performance needs. Clean mechanically or chemically recycled PET with few inclusions and high clarity should have lower scrap rates. Blending ≤15% PCR with virgin PET typically does not significantly increase scrap rates. Forgiving applications and simple container shapes allow wider operating windows and acceptable scrap rates despite variations. Demanding applications like hot fill and CSD require precise material distribution, leading to higher scrap rates.

4.4. Container Performance Differences with PCR PET

4.4.1. Heat-Induced Bottle Shrinkage

Dimensional stability is critical for hot-fill containers exposed to ≥85 °C temperatures. Dimensional instability includes shrinkage, uneven bases, and ovalization. Virgin PET for hot-fill applications has lower diethylene glycol (DEG) levels, as DEG contributes to shrinkage and deformation. PCR, being a mix of PET grades, can have varying DEG content, resulting in variable shrinkage post-hot-fill, generally higher than virgin material containers. Crystallinity management can mitigate shrinkage.

4.4.2. UV Light Transmission Alterations

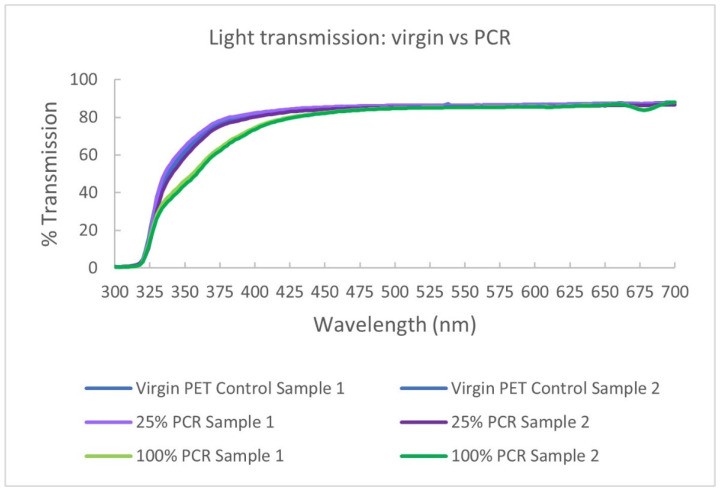

PCR can reduce UV light transmittance. PCR containers may exhibit a yellow/brown tint, especially at higher PCR content. Figure 16 (below) shows UV light transmission reduction (10-50% in 330-400 nm range) in PCR samples compared to virgin PET. This effect depends on PCR grade and lot. UV-sensitive beverages may benefit from this UV-blocking property.

Figure 16. PCR impact on UV light transmission.

4.4.3. Topload Strength Reduction Potential

Topload, or compressive strength, is the bottle’s resistance to buckling under load. PET bottles are known for high topload strength, minimizing secondary packaging. PCR introduction can impact topload. Lower average molecular weight PCR may reduce topload strength. Wide molecular weight distribution in high-PCR content bottles can also lead to variable topload performance.

4.4.4. Burst Strength and Thermal Expansion Changes

Burst strength and thermal expansion, crucial for pressurized CSD containers, can be affected by lower average molecular weight and wider molecular weight distribution in some PCRs. Burst pressures generally decrease, and expansion increases with higher PCR content. Inclusions can lead to unpredictable and lower burst pressures.

5. Applications and Limitations of PCR PET in Beverage Packaging

5.1. Successful Cold-Fill Applications with 100% PCR

100% PCR container options are widely available for cold-fill beverages not requiring carbonation pressure or hot filling. These include still water, chilled juices, tea, coffee, milk, and aseptically filled products. Key functional requirements are product containment, topload strength, and recloseability, without pressure, heat, or vacuum resistance needs.

Color is a critical consumer appeal factor. Toners can be used to influence color. Consumers often perceive slightly yellow containers negatively for clear beverages like water. Toners counteract yellow tones, as shown in Figure 17 (below).

Figure 17. Impact on color with increasing PCR level (image courtesy of Amcor).

Acetaldehyde (AA) can impact flavor profiles. For flavorless products like water, AA levels in PCR PET must be carefully monitored. AA scavengers can mitigate flavor impact risks.

5.2. Heat-Set Bottles for Hot-Filled and Aseptic Products: Emerging Solutions

Hot-filled and some aseptic containers require thermal stability. Aseptic containers sterilized with hot hydrogen peroxide also need heat resistance. Hot-filled containers are sterilized by the hot product. As mentioned previously, thermal deformation is minimized by adequate crystallinity. PCR’s DEG content affects heat resistance. Hot-filled containers also need to withstand vacuum from product cooling. Material distribution is crucial for deformation resistance.

Increased preform heating enhances crystallinity and thermal deformation resistance. However, excessive heating can cause material drift. Asian PCR without reheat additives may struggle to achieve sufficient crystallinity. Balancing process and reheat additive use is essential. 100% PCR heat-set bottles are not yet widely commercialized in North America, but this is expected to change.

5.3. Challenges with Pressurized Containers: CSD Bottles

Pressurized CSD containers pose significant challenges for increasing PCR content. While 10-15% PCR is manageable, 100% PCR is problematic. Very clean, high molecular weight PCR is needed. Inclusions cause ruptures during blow molding, especially in high-stretch areas like base feet.

PCR bottles can exhibit high expansion after filling with pressurized product, potentially causing label issues and reduced shelf life. PCR selection is critical for 100% PCR CSD bottles, requiring clean, high-MW grades, which are currently in limited supply. Some large beverage companies have launched limited 100% PCR CSD bottles due to PCR supply constraints.

6. Regulatory Landscape for PCR PET: Ensuring Food Safety and Compliance

Plastic bottles are favored for beverage packaging due to recyclability and lower carbon footprint. PCR PET must be safe for consumers, especially in beverage applications. Non-food packaging and bottles with non-food-contact approved additives can enter the recycle stream. These non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) are present in PCR PET and can contaminate food. Risk quantification and control are essential for food safety. PET reuse and recycling regulations vary globally. This section outlines key regulations for PCR production and use, providing a framework for PCR acceptability.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates PCR container usage, addressing three main concerns: (1) hazardous contaminant migration, (2) non-food-contact plastic and non-FDA-regulated material interactions, and (3) non-compliant additives in PCR. The FDA assesses PCR production case-by-case, issuing informal notices on process suitability for food contact compliance. Manufacturers seeking food contact grade PCR PET approval must submit process documentation to the FDA, including:

- Controls to prevent non-PET plastics from entering the PCR stream.

- Documentation of efficient contaminant removal, potentially including surrogate contaminant validation and migration modeling to demonstrate reduction below 0.5 ppb.

- Description of intended plastic use, including temperature range, food type, contact duration, and single-use or repeated application.

The FDA considers tertiary recycling (methanolysis and glycolysis) processes suitable for food-contact-grade PET without surrogate testing due to expected high purity. Mechanical recycling requires migration testing to demonstrate residual reduction, with residual migration not exceeding 1.5 μg/person/day estimated daily intake (EDI). Surrogate challenge tests are designed for five migrant categories: (1) volatile polar, (2) volatile non-polar, (3) heavy metal, (4) non-volatile polar, and (5) non-volatile non-polar. Heavy metal surrogate testing is generally waived due to PET’s low metal salt absorption 116.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) regulation 282/2008 requires process approval before PCR production 117. While 5% of PET bottle recycling feed is assumed to be non-food containers on average, it can reach 20% in some cases 118. Final contaminant concentration must be below 3 mg/kg (ppm) per substance.

7. Conclusion and Future Outlook for Pet Bottle Recycling

This comprehensive review highlights PCR PET production, conversion, and regulations for the beverage industry. Sustainability in beverage packaging is driven by material reclaimers, PET recyclers, converters, beverage manufacturers, and responsible consumer contributions. Bottle-to-bottle recycling significantly reduces environmental impact.

PCR PET use has grown dramatically due to collection and recycling technology advancements. Chemical recycling technology commercialization is crucial for future PET recycling, aiming to restore PCR PET to virgin-like performance. Lab-scale technologies are scaling up to pilot and production facilities. Enzyme-based hydrolysis of PET into TPA and EG is one example of advanced recycling 119, with industrial demonstration and commercial facilities planned.

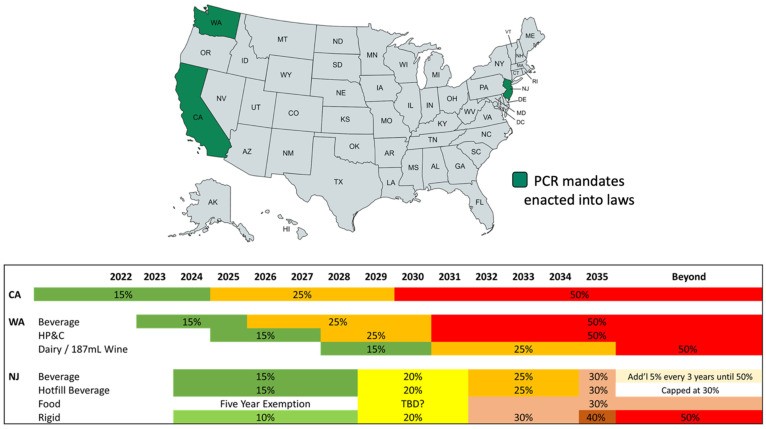

Challenges remain for further PCR PET adoption. Limited PCR PET suppliers and availability can drive up costs and impact quality consistency as demand increases. Public and legislative scrutiny of plastic packaging will continue to spur adoption, with younger consumers demanding increased recycled material use. Future investment in recycling technologies and commercialization must be supported by legislation and increased consumer recycling. PCR mandates in states like California, Washington, and New Jersey (Figure 18 below) are driving demand.

Figure 18. US PCR mandates in California, Washington, and New Jersey.

Methods to detect PCR content in bottles are currently lacking, posing enforcement challenges for PCR mandates. Research in detection methodologies and additive detection in PCR is needed for rapid prototyping and mainstream PCR adoption. Limited scientific data exists on PET grade mixtures and oxygen scavenger interactions with PCR, highlighting areas for future research to support PCR adoption and sustainability goals.

Design enhancements for recycling (design for recycling) are key to improving collection and sortation yields. Organizations like the APR and EPBP provide design guidelines for PET recycling 120. Digital watermarking initiatives like HolyGrail 2.0 aim to enhance PET sortation using digital watermarks for detailed package information 121, 122, 123.

Incorporating PCR content into PET bottles is a crucial step towards a circular economy and zero plastic leakage. Gradual adoption builds confidence in recycling processes, supplier capabilities, cost-effectiveness, package performance, and ultimately, widespread 100% PCR PET bottle adoption, contributing significantly to a more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and D.K.M.; methodology, P.B., G.C., P.K., D.K.M. and J.B.; formal analysis, P.B., G.C., P.K., D.K.M. and J.B.; investigation, P.B.; resources, D.K.M.; data curation, P.B., G.C. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., G.C., P.K. and D.K.M.; writing—review and editing, P.B., G.C., P.K., D.K.M. and J.B.; visualization, P.B., G.C. and P.K.; supervision, D.K.M.; project administration, D.K.M.; funding acquisition, D.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 1023114.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[B1-polymers-14-02366] Soroka, D.S.; Valdes, M.G.; Ashby, R.D.; Farris, R.J.;