For enthusiasts drawn to the darker side of art, Joel-peter Witkin remains a captivating figure. His photography, often featuring corpses and dismembered body parts, continues to fascinate audiences decades after his most controversial works emerged. Witkin’s art isn’t for the faint of heart, but for those who appreciate confronting mortality and the unconventional, his vision is undeniably compelling.

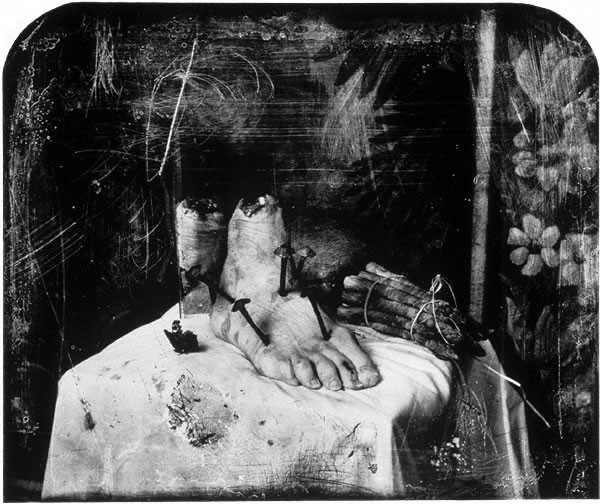

Witkin’s most notorious photographs were largely created in Mexico, where legal loopholes allowed him to explore his artistic themes more freely. He established a relationship with a Mexico City hospital, granting him access to unclaimed bodies and discarded body parts found on the streets. This access became crucial to his artistic process, enabling him to construct his profoundly disturbing yet strangely beautiful compositions.

The origin of Witkin’s macabre fascination is often attributed to a traumatic childhood experience he recounts: witnessing a car accident as a young boy where he saw a decapitated girl’s head roll to his feet. He describes this moment as a pivotal point, shaping his artistic pursuit to confront and transform the grotesque into something meaningful. He stated that his camera became a direct response to this childhood trauma, a way to process and explore the unsettling beauty he found in the face of death.

Poet Bethany Pope, previously featured for her explorations of mortality, penned a poem inspired by Witkin’s aesthetic, which received Witkin’s personal approval. This poem, “Still Life, With Mirror,” delves into the unsettling yet captivating nature of Witkin’s art.

Still Life, With Mirror

(After Joel-Peter Witkin)

I saw something awful today: a severed foot, embedded with five steel nails, positioned in front of a silvered piece of glass. I could not see the blood, it was a corpse-piece, there was nothing to flow, but I could watch the ragged muscle end, the place where the bone emerged, white-grey, from the flaccid base, and I was disturbed. It was, at first, almost like looking at an arrangement of flowers, odd, hard blossoms from an earth-going vase. I could tell that it was human, past tense. And was it the transformation that cut off my breath? The sudden shift from appendage to ornament? Or was it the knowledge that this is something death could be: no chorus, no reunion of voices, but simply, through the act of dissolution, becoming something, to suck away the sacred breath.

Witkin’s oeuvre, exemplified by works like “Still Life with Mirror,” “Feast of Fools,” and “Corpus Medius,” challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable realities and find a perverse beauty in the decaying and the discarded. His art remains a powerful testament to the enduring human fascination with death and the boundaries of artistic representation.