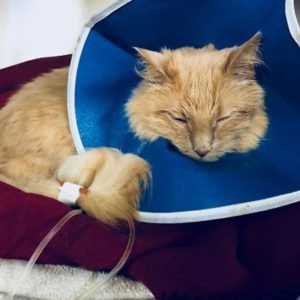

Visiting the veterinarian can be a stressful experience for many pets, and for some, like Hetch-Hetchy, a sweet but anxious cat, it can lead to serious health issues. Hetch’s owner, a veterinarian herself, shares his story to highlight a concerning practice in veterinary medicine: “boxing down” animals using inhalant chambers for anesthesia. This article delves into why this method is harmful and why prioritizing fear-free approaches is crucial for our beloved companions and a move towards truly Free Pets from veterinary anxiety.

Hetch-Hetchy’s history of urethral obstructions (UOs) triggered by veterinary visits underscores the profound impact stress can have on a cat’s health. Despite his owner’s proactive measures, including pre-medication and choosing a trusted specialty hospital, Hetch experienced a traumatic “boxing down” incident. Instead of a quick, injectable anesthetic, he was confined to a box filled with gas anesthesia. The result was a panicked cat and days of hiding and refusing to eat, a clear indication of the psychological trauma inflicted. This experience, unfortunately, is not unique, as the use of inhalant chambers remains a practice in some veterinary settings. It raises a critical question: why are we still using a method that is demonstrably stressful and potentially dangerous when better alternatives exist to ensure fear-free pets?

The Dangers of “Boxing Down” Pets

The practice of using inhalant chambers, or masks, to sedate or induce anesthesia, often referred to as “boxing down” or “masking,” is increasingly recognized as substandard care. While it might seem like a quick solution for uncooperative animals, the risks to both pets and humans, coupled with the significant stress it induces, outweigh any perceived convenience. For pets to be truly free from fear, we must move away from outdated and harmful practices like inhalant chambers.

-

Health Risks for Pets:

Studies have shown that inhalant induction significantly increases the risk of anesthetic fatalities. Brodbelt’s research (2009) highlights that inducing and maintaining anesthesia solely with inhalants elevates anesthetic risk due to the high concentrations needed for induction.

These high concentrations can lead to dangerous drops in blood pressure (hypotension) and respiratory depression. Furthermore, mask or chamber induction prolongs the time without a protected airway (endotracheal tube), increasing the risk of airway obstruction. This makes inhalant induction particularly dangerous for all animals and specifically contraindicated for brachycephalic breeds, known for their respiratory sensitivities.

The excitement phase of anesthesia (Stage II), characterized by delirium and uncontrolled movement, is amplified and prolonged with inhalant induction. This necessitates even higher doses of anesthetic and triggers the release of stress hormones (catecholamines). This surge can cause rapid heart rate (tachycardia), high blood pressure (hypertension), and rapid breathing (hyperventilation), potentially leading to arrhythmias or even cardiac arrest. Even during maintenance, higher concentrations of inhalants are required compared to protocols using premedication or injectable induction drugs.

-

Risks to Veterinary Staff and Owners:

Inhalant anesthetics pose a risk not only to pets but also to the veterinary healthcare team and pet owners present during the procedure. Induction chambers and masks are never entirely leak-proof, leading to environmental contamination with anesthetic gases. Exposure to these waste anesthetic gases has been linked to various health concerns, ranging from reproductive issues like spontaneous abortion (Shirangi et al. 2008) to genetic damage (Cakmak et al. 2019). OSHA warns of potential effects including nausea, dizziness, headaches, fatigue, and more serious long-term risks like sterility, miscarriages, birth defects, cancer, and liver and kidney disease. Prioritizing fear-free practices also means ensuring a safer working environment for veterinary professionals.

-

Increased Stress and Anxiety:

Stress, defined as a threat to an animal’s stable internal environment (homeostasis), is significantly amplified by inhalant chambers. These chambers create an uncontrollable and inescapable stressor, triggering a powerful stress response. For pets to be truly free, we need to minimize these stressors.

The body’s immediate “fight or flight” response (SAM axis activation) to acute stress leads to physical changes like dilated pupils, increased heart rate, and elevated blood pressure. A slower, longer-term stress response (HPA axis activation) involves the release of glucocorticoids, impacting metabolism, immune function, digestion, growth, and reproduction (Hekman, 2014). The overall effect is a mobilization of energy at the expense of essential bodily functions.

Research confirms that inhalant chambers are significant stressors. Studies on mice (Reiter et al 2017) and rabbits (Flecknell et al 1996, 1999) show increased stress hormone levels, agitated behavior, breath-holding, and attempts to avoid the anesthetic vapor, all indicating a highly aversive experience. The slower induction times associated with inhalant anesthetics compared to injectable agents further contribute to struggling and distress (Lester et al 2012).

-

Impact on Morbidity and Mortality:

Stress has well-documented negative impacts on health across species. It weakens the immune system, increasing susceptibility to infection and sepsis, slows wound healing, and elevates the risk of gastric ulcers (Hekman, 2014). In cats, stress is linked to increased bladder permeability in feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) (Westropp 2006). Acute stress can also cause hyperglycemia, even mimicking diabetic levels in some cats (Rand et al 2002), potentially leading to misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment. The physical struggle in an induction chamber can even result in direct injury.

-

Perpetuating Fear and Anxiety:

Animals subjected to inhalant chambers are often those already exhibiting fear and aggression, making restraint challenging. However, using stressful methods like “boxing down” only reinforces and intensifies their fear. Studies show that a significant percentage of even healthy dogs and cats display fear at the veterinary clinic (Döring et al 2009, Quimby et al 2011, Mariti, 2016).

A single traumatic experience can have long-lasting consequences (Koolhaas 1997, Landsberg 2013). Mariti (2016) found that veterinary visit stress worsened handling in other situations for 34% of cats. Inhalant chambers are likely to create a negative association with veterinary visits, making future care even more challenging and hindering the goal of providing free pets from fear at the vet.

-

Compromised Patient Care and Staff Safety:

Increased fear and aggression resulting from stressful procedures like inhalant chamber induction can make subsequent treatments and medication administration more difficult and dangerous, both in the clinic and at home. Dog and cat bites and scratches are major causes of injury to veterinary staff (Jeyaretnam, 2000). Reducing pet fear is essential for staff safety and a more positive work environment.

-

Economic Implications for Veterinary Practices:

Pet stress is a major deterrent for pet owners seeking veterinary care (Volk, 2011). Many cat owners report their cats hate vet visits and experience stress themselves just thinking about it (Volk, 2011). Negative experiences can lead owners to avoid future visits or switch veterinarians (Rodan 2005). Cats are already less likely to receive regular veterinary care compared to dogs (Volk, 2011). Stressful visits further contribute to this gap, hindering veterinary practices from reaching the feline market and providing optimal care. Creating fear-free practices is not only ethically sound but also economically beneficial.

Chemical Restraint: A Kinder Approach, Not a Last Resort

Chemical restraint, using medication to calm and sedate animals, is often necessary and should not be viewed as a last resort, but rather a primary tool for ensuring fear-free pets. Guidelines from the American Association of Feline Practitioners/International Society of Feline Medicine advocate for chemical restraint in situations involving fear, anxiety, stress, aggression, anticipated pain, or when gentle restraint is insufficient for safety.

Fortunately, numerous alternatives to inhalant induction exist, starting with pre-visit pharmaceuticals (PVPs) administered at home.

Pre-Visit Pharmaceuticals (PVPs): Setting the Stage for Calm

PVPs can significantly reduce the need for stressful procedures like inhalant chambers and even injectable sedation or general anesthesia. They make handling easier and more pleasant for everyone involved. The Fear, Anxiety, and Stress (FAS) scale helps assess a pet’s anxiety level and determine if PVPs are indicated.

Pets scoring 2 or 3 on the FAS scale (showing slight disinterest in treats, fidgeting) exhibit moderate anxiety and benefit from PVPs. Scores of 4 or 5 (no interest in treats, fight/flight/freeze response, aggression) indicate high anxiety, requiring PVPs and potentially injectable sedation. Veterinary teams should proactively discuss a pet’s history of fear and anxiety during appointment scheduling and recommend appropriate PVPs like gabapentin, trazodone, buprenorphine, transmucosal dexmedetomidine, or benzodiazepines.

Examples of Effective PVPs

It’s crucial to test PVPs at home before a veterinary visit to understand their effects on individual pets. Factors like onset time, duration, and potential side effects need to be evaluated to optimize the PVP plan.

-

Gabapentin: While not specifically labeled for anxiety, gabapentin is increasingly used for its calming effects in pets and humans. Studies show it reduces stress during transport and veterinary exams in cats (van Haaften et al 2017). Dosage varies based on cat size. Side effects can include sedation, ataxia, and increased appetite. Administer 3 hours prior to the visit, potentially with a dose the night before.

-

Trazodone: This serotonin antagonist reuptake inhibitor is an effective anxiolytic and sedative for cats. Administer 50-100mg per cat 3 hours before the visit. Side effects may include drowsiness, gastrointestinal upset, or paradoxical excitation. Test dosing at home is essential to determine the correct dose.

-

Benzodiazepines (Lorazepam, Alprazolam): These potent anxiolytics act quickly and are suitable for severe anxiety, but not recommended for aggressive pets due to potential paradoxical excitation. Test at home to assess for adverse reactions like ataxia, sedation, or increased appetite. Lorazepam and alprazolam are commonly used in cats, with lorazepam preferred for geriatric or liver-compromised patients. Administer 2-3 hours prior to the visit.

-

Buprenorphine: A partial mu-opioid agonist providing analgesia and mild sedation, buprenorphine is useful in balanced sedation protocols. Administer transmucosally at 0.01-0.02 mg/kg, 2-3 hours before the visit. Side effects include sedation, and potential temperature changes.

-

Sileo (Transmucosal Dexmedetomidine): FDA-approved for noise aversion in dogs, Sileo is used off-label for anxiety in cats and dogs. It’s fast-acting, minimally sedating, and can be combined with buprenorphine for increased effect. Administer 60 minutes before the visit.

PVPs not only reduce pet anxiety but also facilitate safer and easier administration of injectable premedications and anesthetics when needed.

Transportation and Arrival: Maintaining Calm

Advise pet owners to transport pets in soft, easily accessible carriers. Upon arrival, immediately place the carrier in a quiet room, covering cat carriers with Feliway-sprayed towels to further reduce stress.

Gentle handling and Fear Free techniques are paramount for minimizing stress and maximizing safety during sedation or anesthesia (Yin 2009, Rodan et al 2011). Appropriate handling can even reduce the need for full anesthesia.

Carrier Removal and Gentle Restraint

Avoid forcefully pulling pets from carriers or shaking them out. For fearful pets in soft carriers, intramuscular injections can be administered directly through the carrier. For hard carriers with removable tops, gradually remove the top while draping a towel over the pet, providing secure and gentle restraint for examination and injections.

Injectable Sedation Options

If deeper sedation is needed, balanced sedation protocols using injectable medications are preferred over inhalant chambers. Options include opioids, dexmedetomidine/medetomidine, midazolam, alfaxalone, Telazol, and ketamine. Propofol can be added if IV access is possible. Be aware that pre-existing fear and stress can affect the efficacy of injectable sedatives, potentially requiring dose adjustments. Always provide supplemental oxygen and monitoring for deeply sedated or anesthetized patients.

-

Opioids (Methadone, Morphine, Hydromorphone, Buprenorphine, Butorphanol): Mu-agonists like methadone, morphine, and hydromorphone provide strong analgesia for painful procedures. Buprenorphine offers moderate analgesia and sedation. Butorphanol is a mild, short-acting sedative, often combined with alpha-2 agonists. Pre-treatment with anti-emetics like maropitant is recommended due to potential nausea.

-

Alpha-2 Agonists (Dexmedetomidine, Medetomidine): These provide rapid sedation and analgesia with reversible effects. They reduce the need for induction and maintenance anesthetics but can cause initial hypertension followed by bradycardia, and potential nausea. Use cautiously in patients with cardiovascular disease.

-

Alfaxalone: An injectable anesthetic with rapid onset and short duration, alfaxalone is suitable for sedation or anesthesia. It has minimal side effects and can be combined with other premedications. IM administration is practical for cats but less so for larger animals.

-

Ketamine: A dissociative anesthetic effective IM, ketamine provides analgesia at lower doses. Often combined with benzodiazepines for induction. Use cautiously in patients with seizures, intracranial disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or renal disease in cats.

-

Telazol (Tiletamine/Zolazepam): A combination of a dissociative and benzodiazepine, Telazol is excellent for highly fearful animals due to its small volume for IM administration and rapid onset. Use with caution in patients with pancreatic, respiratory, or cardiovascular disease, and follow similar precautions as with ketamine.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Fear-Free Practices for Healthier, Happier Pets

Inhalant chambers and masks are outdated, dangerous, and stressful for pets and veterinary staff alike. Stress negatively impacts health and well-being. With numerous safer and more humane alternatives available, inhalant chambers should be eliminated from veterinary practice. Prioritizing fear-free approaches, including pre-visit pharmaceuticals, gentle handling, and balanced sedation protocols, is essential for creating positive veterinary experiences, improving patient health, and fostering stronger pet-owner-veterinarian relationships. By embracing fear-free methods, we can move towards a future where veterinary visits are no longer a source of terror for our beloved animal companions, ensuring truly free pets in every sense.

Table: Stages and Planes of Anesthesia

| Stage | Description | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Disorientation, sedation | Occurs following premedications |

| 2 | Delirium, excitation, uncontrolled movement | Occurs during induction and recovery. Anesthetic plans should be designed so the patient spends minimal time in this phase. Induction should be rapid (use injectable drugs) and recovery should include sedatives if excitement/dysphoria occurs. |

| 3 | Unconsciousness, surgical plane of anesthesia | Plane 1: Light anesthesia, depth inadequate for moderately-severely painful procedures unless local anesthetic blocks are part of the protocol. Plane 2: Moderate anesthesia, adequate for painful procedures with administration of appropriate analgesia. Plane 3: Deep anesthesia, required if analgesia is not part of the protocol. More physiologic depression occurs in this plane than in previous planes. Plane 4: Excessively deep anesthesia, dangerous physiologic depression. Turn the vaporizer off and start ventilating for the patient to speed inhalant elimination. |

| 4 | Too deep! | This stage is between respiratory arrest and circulatory collapse. Take the patient off the anesthetic and prepare for CPR. |

References

Brodbelt D. Perioperative mortality in small animal anaesthesia. The Veterinary Journal. 2009; 182:152–161.

Çakmak G, Eraydın D, Berkkan A, Yağar S, Burgaz S. Genetic damage of operating and recovery room personnel occupationally exposed to waste anaesthetic gases. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2019 Jan;38(1):3-10.

Costa RS, Karas AZ, Borns-Weil S. Chill Protocol to Manage Aggressive & Fearful Dogs. Clinicians Brief May 2019.Crowell-Davis S, Murray T, Mattos de Souza Dantas L. Veterinary Psychopharmacology. 2nd Edition. Wiley Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ, 2019.

Dess N.K., Linwick D., Patterson J., Overmier J.B., Levine S. Immediate and proactive effects of controllability and predictability on plasma cortisol responses to shocks in dogs. Behav. Neurosci. 1983;97:1005–1016

Döring D, Roscher A, Scheipl F, Küchenhoff H, Erhard MH. Fear-related behaviour of dogs in veterinary practice. Vet J. 2009 Oct; 182(1):38-43.

Flecknell P, Cruz I, Liles J, Whelan G. Induction of anaesthesia with halothane and isoflurane in the rabbit: a comparison of the use of a face-mask or an anaesthetic chamber. Lab Anim. 1996: 30(1):67-74.

Flecknell P, Roughan J, Hedenqvist P. Induction of anaesthesia with sevoflurane and isoflurane in the rabbit. Lab Anim. 1999 (33):41-46.

Grubb T, Sager J, Gaynor JS, Montgomery E, Parker JA, Shafford H, Tearney C. 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2020; In press.

Hekman JP, Karas A, Sharp CR. Psychogenic stress in hospitalized dogs: Cross species comparisons, implications for health care, and the challenges of evaluation. Animals. 2014; 4.2:331-347.

Jeyaretnam J, Jones H, Phillips M. Disease and injury among veterinarians. Aust Vet J. 2000 Sep; 78(9):625-9.

Koolhaus, J.M., Meerlo, P., DeBoer, S.F., Strubbe, J.H., Bohus, B., 1997. The temporal dynamics of the stress response. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 21, 775–782.

Landsberg G. Behavioral Management of Fear and Aggression in Your Patients, 2016, pp 519-521. https://www.fetchdvm360.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CVCKC-2016-505-524-low-stress_pet-friendly_practice.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2020.

Landsberg G., Hunthausen W., Ackerman L. Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; Edinburgh, Scotland: 2013.

Lester P, Moore R, Shuster K, Myers D. Chapter 2- Anesthesia and Analgesia. In “The Laboratory Rabbit, Guinea Pig, Hamster and Other Rodents.” American College of Laboratory Medicine. Academic Press, London, 2012; p 33-56.

Lloyd J. Minimizing stress for patients in the veterinary hospital: Why it is important and what can be done about it. Vet Sci. 2017;4(22):1-19.

Mariti C, Bowen J, Campa S, Grebe G, Sighieri C, Gazzano A. Guardians’ Perceptions of Cats’ Welfare and Behavior Regarding Visiting Veterinary Clinics. J Applied Animal Welfare Science. 2016, 19(4):375-384.

Martin K, Martin D. FAS Scale. Fear Free, 2007.

National Research Council (US) Committee on Recognition and Alleviation of Distress in Laboratory Animals. Recognition and Alleviation of Distress in Laboratory Animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2008.

OSHA: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/wasteanestheticgases/index.html

OSHA: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/wasteanestheticgases/solutions/index.html

Quimby J. Maropitant Use in Cats, 2020. Available online: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/maropitant-use-in-cats/. Accessed 13 June 2020.

Quimby J, Smith M, Lunn K. Evaluation of the effects of hospital visit stress on physiologic parameters in the cat. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011, 13:733-737.

Rand JS, Kinnaird E, Baglioni A, et al. Acute stress hyperglycemia in cats is associated with struggling and increased concentrations of lactate and norepinephrine. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16(123-132).

Reiter C, Christy A, Olsen C, Bentzel D. Response to Isoflurane-induced anesthesia in C57BL/6J mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2017, 56(2):118-121.

Robertson SA, Gogolski SM, Pascoe P, Shafford HL, Sager J, Griffenhagen GM. AAFP Feline Anesthesia Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2018 Jul;20(7):602-634.

Rodan I. Understanding feline behavior and application for appropriate handling and management. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 2010;24(4):178-188.

Rodan I, Cannon M. Chapter 9: The Cat in the Veterinary Practice. In “Feline Behavioral Health and Welfare.” Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015, p 102-111.

Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, Gagnon AC, Heath S, Landsberg G, Seksel K, Yin S. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2011 May;13(5):364-7.

Scheftel JM, Elchos BL, Rubin CS, Decker JA. Review of hazards to female reproductive health in veterinary practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017 Apr 15;250(8):862-872.

Shafford H. Serenity Now: Practical Sedation Options for Cats and Dogs, 2016. https://vetanesthesiaspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/SedationOptions_DogsAndCats_Shafford_updated2017.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2020.

Shirangi A, Fritschi L, Holman CD. Maternal occupational exposures and risk of spontaneous abortion in veterinary practice. Occup Environ Med. 2008 Nov;65(11):719-25.

Steagall PV, Monteiro-Steagall BP, Taylor PM. A review of the studies using buprenorphine in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2014 May-Jun;28(3):762-70.

Subramaniam K, Subramaniam B, Steinbrook RA. Ketamine as adjuvant analgesic to opioids: A quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Anesth Anal 2004; 99(2):482-495.

Tynes V.V. The Physiologic Effects of Fear, 2014. Available online: http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/physiologic-effects-fear. Accessed 13 April 2020.

Van Haaften K, Forsythe L, Stelow E, Bain M. Effects of a single reappointment dose of gabapentin on signs of stress in cats during transportation and veterinary examination. J of Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;15(10):1175-1181.

Volk JO, Felsted KE, Thomas JG, Siren CW. Executive summary of the Bayer veterinary care usage study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011 May 15; 238(10):1275-82.

Westropp JL, Kass PH, Buffington CA. Evaluation of the effects of stress in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:731-736.

Yin S. Low stress handling, restraint and behavior modification of dogs and cats. CattleDog Publishing, 2009.

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.