For centuries, foxes have captured human imagination as symbols of wildness and cunning. From folklore to popular culture, these creatures are often portrayed as inherently untamable. However, a groundbreaking experiment in Siberia has challenged this very notion, giving rise to the Domesticated Pet Fox. This remarkable project, spanning over six decades, has not only rewritten our understanding of domestication but also opened up the possibility of welcoming a fox into our homes, albeit with unique considerations.

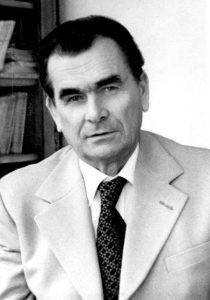

The story of the domesticated fox begins in the Soviet Union in the 1950s, a period marked by both scientific curiosity and political constraint. Dmitry Belyaev, a geneticist at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, embarked on a bold mission to unravel the mysteries of domestication. Inspired by the domestication of dogs, Belyaev hypothesized that the key to taming wild animals lay in selective breeding for tamability itself. Facing the shadow of Lysenkoism, a politically motivated anti-genetics movement, Belyaev cautiously initiated his experiment, choosing foxes for their canine lineage and their reputation for untamed behavior.

Belyaev and his team started with silver foxes sourced from fur farms across the Soviet Union, selecting individuals that exhibited the least aggression towards humans. This initial selection was crucial, as it laid the foundation for generations of breeding focused solely on tameness. To ensure that the observed changes were indeed genetic, a control group of foxes was also bred, selected for their aggressive behavior towards humans. This contrasting breeding program provided a powerful comparison, highlighting the heritability of tameness in foxes.

The results of this long-term experiment were nothing short of astonishing. Over generations, the selectively bred foxes displayed increasingly dog-like behaviors. They eagerly sought human contact, wagged their tails, whined for attention, and even licked and nuzzled their handlers. By the tenth generation, a significant portion of fox pups exhibited “elite” tameness, a category defined by their eagerness to interact with humans. This percentage surged to 70-80% in later generations, demonstrating the rapid pace at which domestication could occur through focused selection. Lyudmilla Trut, a key researcher who continued Belyaev’s work after his death, documented these remarkable transformations, solidifying the experiment’s significance in understanding domestication.

Beyond behavioral changes, the domesticated foxes also developed unexpected physical traits, mirroring the morphological changes observed in other domesticated species. These “domestication syndrome” traits included piebald coats, floppy ears persisting into adulthood, and curled tails – features rarely seen in wild foxes. Jennifer Johnson, a biologist collaborating with Anna Kukekova, another prominent researcher in the project, noted the prolonged floppiness of ears in domesticated fox pups, a characteristic reminiscent of puppies and linked to developmental changes during domestication.

Scientists delved into the genetic underpinnings of these transformations, seeking to identify the genes responsible for tameness and associated traits. Research revealed that tameness is not governed by a single gene but rather a complex interplay of multiple genes influencing various aspects of behavior, from boldness and activity levels to the fundamental “nice versus mean” temperament. The ongoing sequencing of the fox genome by Kukekova’s lab promises to further illuminate the intricate genetic architecture of domestication, providing valuable insights into evolutionary biology and animal behavior.

However, the journey of the domesticated pet fox has not been without its challenges. The collapse of the Soviet Union brought financial hardship to the experiment, threatening its continuation. To ensure the survival of the project, researchers had to explore alternative funding sources, including selling fox pelts and, more recently, selling the domesticated foxes themselves as pets.

Today, these remarkable animals are available to individuals and organizations worldwide, albeit with a significant price tag and legal considerations. The Judith A. Bassett Canid Education and Conservation Center in California is one such organization that houses domesticated foxes, using them as ambassadors to educate the public about foxes and conservation. David Bassett, president of the center, recounts the dog-like behavior of their domesticated fox Boris, who eagerly greets visitors and solicits attention, showcasing the profound impact of domestication on fox behavior.

Considering a domesticated pet fox? It’s crucial to be aware of the realities. Bringing a Siberian domesticated fox to the United States can cost upwards of $9,000, and many states have regulations or outright bans on keeping foxes as pets. Even domesticated foxes, while significantly tamer than their wild counterparts, retain some wild instincts. Amy Bassett, founder of the Canid Conservation Center, cautions that while dogs are highly trainable, foxes, even domesticated ones, can exhibit unpredictable behaviors that may be challenging to manage. Anecdotes of foxes urinating in coffee cups serve as humorous reminders of their unique nature.

In conclusion, the domesticated pet fox represents a fascinating intersection of scientific discovery and the age-old human desire to connect with the animal kingdom. The Siberian fox experiment stands as a testament to the power of selective breeding and provides invaluable insights into the process of domestication. While the idea of a domesticated fox as a pet is captivating, prospective owners must carefully consider the legal, financial, and behavioral realities before welcoming one of these extraordinary creatures into their lives. The domesticated pet fox is not just a pet; it’s a living embodiment of a scientific revolution and a unique glimpse into the ongoing evolution of animal-human relationships.