The story of John Peter Zenger is a pivotal chapter in the history of freedom of the press, especially in the early American colonies. His landmark 1735 trial, though not immediately changing the legal landscape, became a powerful symbol in the burgeoning fight for free speech and against governmental overreach. To understand Zenger’s significance, it’s crucial to delve into the context of colonial New York and the events that led to his celebrated case.

In the 18th century, New York was under British rule, and political tensions were brewing. The only established newspaper at the time was the New York Gazette, founded in 1725. This publication, run by public printer William Bradford, consistently supported the Governor and the ruling administration. However, this monopoly of information was challenged when Governor William Cosby made a controversial decision.

The spark that ignited the Zenger affair was Governor Cosby’s removal of Chief Judge Lewis Morris in 1733. Morris had dissented in the case of Cosby v. Van Dam, and Cosby’s swift action was perceived as an attack on judicial independence. In response, Morris and his allies, prominent attorneys James Alexander and William Smith, decided to establish an independent voice. This led to the creation of the New-York Weekly Journal, the colony’s first newspaper designed to challenge the official narrative. James Alexander took on the role of editor, using the Journal as a platform to criticize Governor Cosby’s administration. Through sharp articles, satire, and lampoons, the New-York Weekly Journal accused Cosby of tyranny and trampling upon the rights of the people. Governor Cosby, feeling the sting of public criticism and dissent, resolved to silence the New-York Weekly Journal and its dissenting voice.

John Peter Zenger, a printer by trade, became the central figure in this conflict. As one of the few skilled printers in the province, he was responsible for physically producing the New-York Weekly Journal. The Cosby administration, perhaps believing that shutting down the printer would effectively shut down the newspaper, decided to target Zenger legally. Daniel Horsmanden, a recently arrived English barrister favored by the Governor, was tasked with examining the New-York Weekly Journal for content that could be classified as seditious libel.

Seditious libel, a serious offense at the time, was broadly defined as the intentional publication of written criticism against public figures, laws, or established institutions without lawful justification. Governor Cosby’s administration convened two grand juries in 1734 to consider indicting John Peter Zenger for seditious libel. However, despite the evidence presented, neither grand jury was willing to indict Zenger. This resistance indicated a growing public sentiment against the Governor’s heavy-handed tactics and a nascent appreciation for freedom of expression, even if the legal definition of seditious libel remained in place.

Undeterred by the grand juries’ refusals, Governor Cosby resorted to governmental censorship. He requested the Assembly to order the public burning of issues of the New-York Weekly Journal by the public hangman, a symbolic act meant to suppress dissent. However, the popularly elected Assembly refused to comply with this request, demonstrating a degree of independence from the Governor’s will. The Governor’s Council then ordered the sheriff to burn the papers publicly. When the sheriff sought authorization from the Court of Quarter Sessions, a court of aldermen, the court adjourned without issuing the order, effectively preventing the public burning of the newspapers. This series of rebuffs highlighted the Cosby administration’s increasing isolation and the growing opposition to its attempts to stifle the press.

Facing continued resistance, the Cosby administration turned to a legal maneuver known as an information. This unpopular legal procedure allowed the Attorney General to bring a prosecution without a grand jury indictment, bypassing the need for public consent and further emphasizing the administration’s authoritarian approach. Attorney General Richard Bradley, acting on behalf of the Crown, filed an information before the Supreme Court of Judicature. Cosby’s allies within the court, Chief Justice James De Lancey and Justice Frederick Philipse, issued a bench warrant for John Peter Zenger’s arrest based on this information. On November 17, 1734, Zenger was arrested and imprisoned in New York’s Old City Jail.

James Alexander and William Smith, Zenger’s attorneys and the driving forces behind the New-York Weekly Journal, immediately sought a writ of habeas corpus. Zenger was brought before Chief Justice De Lancey, who scheduled a hearing for November 23, 1734. At the hearing, the court set bail at an exorbitant £400, an amount far beyond Zenger’s financial means. Unable to pay, John Peter Zenger was remanded back to jail to await trial. Despite his imprisonment, Zenger’s wife, Anna, and his apprentices bravely continued to publish the New-York Weekly Journal, missing only one issue. This continuity not only kept the newspaper alive but also galvanized public support for Zenger and his cause.

Defending John Peter Zenger against seditious libel presented significant legal hurdles for Alexander and Smith. The prevailing legal doctrine at the time held that the truth of the published statements was irrelevant in a seditious libel case. Furthermore, the jury’s role was limited to determining whether the defendant had indeed published the allegedly libelous material. If the jury affirmed publication, it was then up to the judges, in this case Cosby’s allies De Lancey and Philipse, to decide whether the statements constituted seditious libel. This legal framework heavily favored the prosecution and made Zenger’s defense an uphill battle.

At Zenger’s arraignment in April 1735, his attorneys launched a bold challenge to the legitimacy of the court itself. Alexander and Smith argued that Governor Cosby’s earlier dismissal of Chief Justice Lewis Morris in 1733 was unlawful, thus invalidating De Lancey’s subsequent appointment as Chief Justice. They further questioned the commissions of all the judges, arguing that their appointments “at the Governor’s pleasure” made them beholden to executive power rather than independent arbiters of justice. The court, predictably, rejected these arguments outright. Chief Justice De Lancey famously retorted, “You have brought it to that point that either we must go from the bench or you from the bar.” When Alexander and Smith refused to retract their challenge, the court took drastic action, disbarring both attorneys on April 16, 1735, effectively removing Zenger’s chosen legal representation.

Left without his original counsel, Zenger petitioned the court to appoint him a lawyer. John Chambers, a young, newly admitted attorney known to be loyal to Cosby, was assigned to Zenger’s defense. However, Chambers surprised many by diligently representing Zenger’s interests. He twice challenged the jury selection process, ensuring that the jury ultimately empaneled was not biased against Zenger. The chosen jurors were: Thomas Hunt (Foreman), Harmanus Rutgers, Stanley Holmes, Edward Man, John Bell, Samuel Weaver, Andries Marschalk, Egbert van Borsom, Benjamin Hildreth, Abraham Keteltas, John Goelet, and Hercules Wendover.

Chief Justice De Lancey adjourned the court until August 4, 1735, granting Chambers time to prepare the defense. This delay also provided Zenger’s supporters with an opportunity to secure the representation of Andrew Hamilton, a highly respected and preeminent attorney from Philadelphia. When the trial commenced in City Hall on August 4, Attorney General Richard Bradley presented the “information,” and John Chambers entered a plea of “not guilty” on Zenger’s behalf. Chambers then outlined the case, emphasizing the prosecution’s burden to prove Zenger’s responsibility for the alleged libel and expressing doubt in their ability to do so. Following Chambers’s remarks, Andrew Hamilton rose to address the court, taking a dramatic and unexpected approach. Hamilton preempted Bradley’s case by openly admitting that John Peter Zenger had indeed published the New-York Weekly Journal.

Hamilton’s defense then shifted from denying publication to arguing for the right to publish the truth. In his powerful address to the jury, Hamilton urged them to consider the truth of the statements published in the New-York Weekly Journal. He argued that in a free society, citizens have the right to criticize the government, and that truth should be a defense against libel, especially when criticizing those in power. Hamilton concluded his impassioned plea with words that would become immortalized in the fight for freedom of the press:

The question before the Court and you, Gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every free man that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.

Despite Chief Justice De Lancey’s explicit instructions that the jury should only decide whether Zenger had published the New-York Weekly Journal – and not whether the content was libelous – the jury defied the court’s direction. After brief deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty” of publishing seditious libel. A wave of cheers erupted in the packed courtroom. Andrew Hamilton was hailed as a hero. He was honored with a celebratory dinner at the Black Horse Tavern, given the freedom of the City, and saluted with cannons upon his departure. John Peter Zenger was released from prison the day after the trial, returning to his printing business and publishing his own account of the trial, further solidifying his place in history.

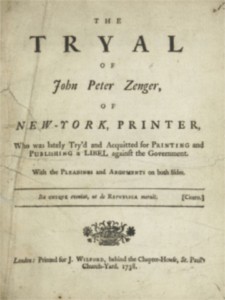

Cover page of The Tryal of John Peter Zenger

Cover page of The Tryal of John Peter Zenger

While the Zenger case did not immediately change the legal definition of seditious libel or establish a legal precedent for freedom of the press, its impact was profound. The trial significantly influenced public opinion and shaped the evolving understanding of free speech in America. Decades later, the principles championed in Zenger’s defense would find their way into the United States Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Sedition Act of 1798. The Zenger case demonstrated the growing assertiveness of the legal profession in the colonies and underscored the power of the jury as a check on executive authority. Gouverneur Morris, a Founding Father and grandson of the ousted Chief Judge Lewis Morris, aptly described the Zenger case as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America!” The legacy of John Peter Zenger continues to resonate today as a symbol of courage in the face of oppression and a landmark moment in the ongoing struggle for freedom of the press.

Sources

Paul Finkelman. Politics, the Press, and the Law: the Trial of John Peter Zenger in American Political Trials Michal R. Belknap (ed). Connecticut (1994)

Donald A. Ritchie. American Journalists: Getting the Story. New York (1997)

Eben Moglen. Considering Zenger: Partisan Politics and the Legal Profession in Provincial New York, 94 Columbia Law Review 1495 (1994)

Endnotes

1) This proved not to be the case. Zenger’s wife, Anna, and his apprentices continued printing the paper. Only one issue was missed. The continued publication of the newspaper built support for Zenger cause.

2) Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Free Speech in the United States (1941)

3) In Tudor and Stuart England, the ceremonial burning of books and other printed material by the public hangman symbolically reinforced the power of the government to restrict freedom of expression.

4) The Sheriff, with several officials loyal to the administration in attendance, had the papers burned in public by his personal servant.

5) As such, this case is also referred to as Attorney General v. John Peter Zenger; either reference is correct.

6) At a later date, the Lords of the Board of Trade in London would decide that Cosby’s removal of Chief Judge Lewis Morris without an inquiry, had been illegal.

7) Maturin L. Delafield. William Smith, Judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York. Reprinted from”The Magazine of American History,” of April and June, 1881

8) Statesman, founding father and grandson of Chief Judge Lewis Morris.