Zrenjanin, a city painted with the hues of history, initially charmed with its quiet squares and whispers of a bygone era. The rain had retreated, the beer was a pleasant memory, and the echoes of pizza lingered faintly as I returned to Trg Slobode, or Freedom Square, Zrenjanin’s central hub. This Vojvodina square unfolded with typical elegance, a spacious area embraced by the city’s significant buildings, each narrating a silent story of social vibrancy. The City Hall, a structure of green and blue from the 19th century, stood proudly – once a beacon of modernity in the Kingdom of Hungary. Beside it, the Cathedral of St. John of Nepomuk, erected in 1867, possessed a graceful yet understated presence. While many small-town churches charm, this one, dedicated to the famously discreet Czech saint, didn’t immediately strike as exceptional, though such dedications are found across the continent. My attention was drawn to the square’s centerpiece: a statue of a dignified man on horseback. Drawn closer, I discovered it was Peter I Karadjordjevic, the last King of Serbia and the first King of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes – a figure crowned with a magnificent mustache and fondly remembered as the Old King, or, as history fondly calls him, Peter The Liberator.

From Heir Apparent to International Student: The Early Life of Peter the Liberator

Born in 1844, Peter’s lineage was steeped in Serbian history. He was the grandson of the leader of the First Serbian Uprising, Karađorđe Petrović, placing him in the orbit of royal expectations from birth, amplified by the privilege of wealth. His arrival, however, was met with mixed emotions by his parents, still grieving the loss of their firstborn. In that era, as the third son, Peter’s birth merely confirmed royal fertility. Fate, however, had other plans. The death of his second-born brother in 1847 dramatically reshaped young Peter’s destiny, casting him as the heir to the Serbian throne.

A more profound shift occurred in 1858 when Peter’s father, Prince Alexander Karađorđević, was dethroned by the rival Obrenović dynasty. This deposition was a continuation of the deep-seated animosity between the two Serbian families. Suddenly, Peter’s world turned upside down. He transitioned from a prince in line for the throne to an international student, first in Geneva and later in Paris. However, he was not just any student. Peter excelled in his studies, though as a wealthy student in these vibrant cities, the bar for failure was arguably quite high. Paris became his formative playground. He immersed himself in the city’s cultural and intellectual currents, exploring painting, philosophy, democratic ideals, and art – experiences that would shape his worldview. Yet, the call of his homeland and a thirst for action soon drew him back to the Balkans. He joined the Herzegovinian uprising against Ottoman rule, a conflict that promised action over academic pursuits. Choosing military strategy over museum visits, Peter’s involvement in the uprising, however, brought him unwanted attention from the ruling Obrenović family. They viewed his presence amidst the Bosnian and Herzegovinian rebels with suspicion, leading to accusations of treachery. Attempts at reconciliation between the Karađorđević and Obrenović families proved futile. Peter was condemned to death in absentia by hanging. Fortunately, he was beyond their reach, having sought refuge in Montenegro where he married Princess Zorka, daughter of Prince Nicholas I, further complicating the region’s intricate geopolitical landscape.

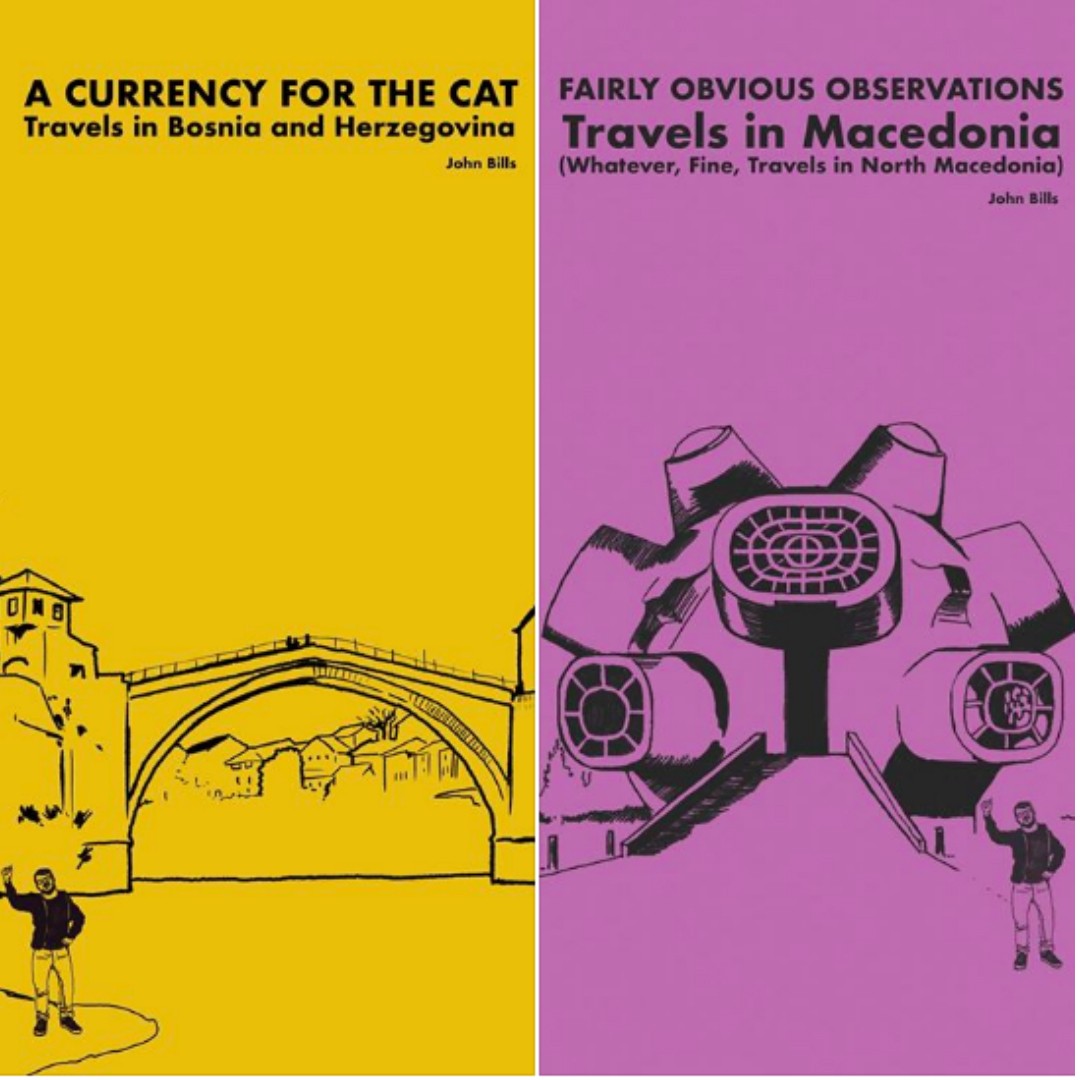

Covers

Covers

The Crumbling Grace of Zrenjanin and the Weight of History

Lost in contemplation before Peter’s statue in Zrenjanin, these historical details were not at the forefront of my mind. Instead, I was captivated by the city’s atmosphere, a palpable sense of faded grandeur. Venturing away from Freedom Square towards the main pedestrian street, I was enveloped by a quietude intensified by the recent rain. This illusion of solitude soon dissolved with the boisterous laughter of children, their amusement seemingly directed my way, grounding me back in the present.

Zrenjanin’s main street presented itself as an open-air museum of architecture, showcasing magnificent buildings that whispered tales of former glory. The architectural procession began with the Bukovac Palace, a Neo-Renaissance gem erected in 1905 by the merchant family it’s named after. Further along, Bence’s House, a department store from 1909, displayed its grandeur with large windows and pink arches. Financed by furniture magnate Miksa Bence, it was envisioned as a futuristic showroom, now serving as a window into the past. Many buildings on this street seemed to exist on borrowed time, sustained by the memory of their beauty and the hope of future restoration. For me, the Šeherezada, an almost Turkish-style building in yellow and orange, stood out as the street’s most enchanting structure. It seemed transported from a Mediterranean coast or Islamic Spain, its lower floors now housing a clothes shop and a currency exchange, a blend of historical aesthetics and modern commerce.

From Exile to Acclamation: Peter’s Return and Reign as King

Overwhelmed by the architectural echoes of the past, I circled back towards Freedom Square and the statue of Peter, the man who would become known as Peter the Liberator. His personal life mirrored the tumultuous nature of his family’s history. His marriage, like his parents’, was marked by both joy and sorrow. He had five children but endured the loss of two, the second of which coincided with the death of his wife during childbirth – a double tragedy. Despite personal setbacks, Peter remained politically astute. He contemplated overthrowing the Obrenović dynasty but ultimately chose to return to Geneva, biding his time. He remained in Geneva until 1903. The political landscape shifted dramatically due to the unpopularity of the Obrenović heir, creating an opportune moment for the Karađorđević family to reclaim power. The 1903 coup d’état unfolded decisively, resulting in the assassination of King Alexander Obrenović and Queen Draga. The Karađorđević dynasty was reinstated, and Peter was greeted with widespread acclaim in Belgrade, hailed as the ‘first Yugoslav king’. The winds of change were indeed blowing across the Balkans.

Peter’s coronation in 1904 was deliberately timed to coincide with the centennial of the First Serbian Uprising, symbolically linking him to his grandfather’s legacy. He quickly became seen as a symbol of modern, progressive leadership in the often-turbulent Balkans. His reign is fondly remembered in Serbia as a golden age of cultural and creative flourishing. Much of this positive historical perception is linked to territorial gains, particularly the regaining of Kosovo, during the First Balkan War. However, the near-constant warfare in Serbia from 1912 to 1918 took a toll on Peter’s health, exacerbated by his advancing age. He passed away in 1921, his death attributed to old age and declining health. In honor of their king, the town of Zrenjanin was renamed Petrovgrad (Peter’s City), a name it retained until 1946. Today, a movement exists to restore the name Petrovgrad, a testament to the enduring legacy of Peter the Liberator and his profound impact on Serbian history and national identity.

Further Exploration: To delve deeper into the history of Yugoslavia and the Balkans, explore the books by John Bills, offering insightful perspectives on the region’s past and present. This link provides access to his literary works, a valuable resource for anyone interested in understanding this fascinating corner of Europe.

Alt text for image covers.jpg: Book covers designed by John Bills, showcasing his publications on Yugoslavia, ideal for readers interested in Balkan history and culture.