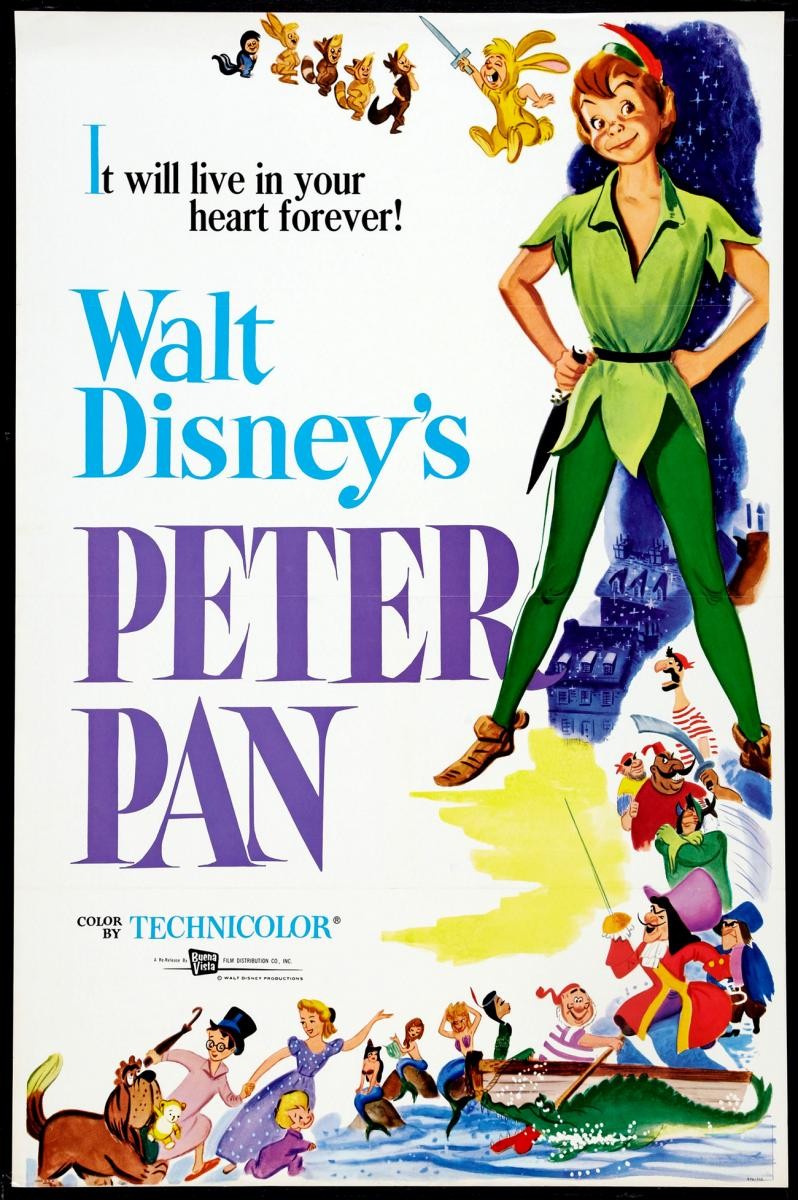

Walt Disney’s 1953 animated classic, Peter Pan, remains a beloved cinematic journey into a world where childhood never ends. Based on J.M. Barrie’s timeless play and book, this Disney rendition has captivated audiences for generations with its vibrant animation, memorable characters, and enchanting story. But beyond the pixie dust and pirate battles, Disney’s Peter Pan offers a rich tapestry of themes and cultural context worth exploring. Let’s dive into why this 1953 masterpiece continues to resonate, examining its strengths, its complexities, and its enduring appeal.

From Stage to Screen: The Journey of Disney’s Peter Pan

The tale of Peter Pan held a special place in Walt Disney’s heart. He even played Peter Pan in a school production in his youth. The idea of adapting Peter Pan into an animated feature film was considered as early as the 1930s, placing it alongside Snow White and Pinocchio in Disney’s ambitious early animation plans. However, World War II significantly disrupted studio operations, putting Peter Pan into development limbo. Early character maquettes for the film can even be glimpsed in the 1941 film The Reluctant Dragon, hinting at the project’s long gestation period.

Following the triumphant success of Cinderella in 1950, Disney revisited Peter Pan with renewed vigor. The final product, released in 1953, was met with mixed reactions from critics and even Walt Disney himself, who felt the film had some shortcomings. Despite initial reservations, audiences warmly embraced Disney’s Peter Pan, and it has since solidified its status as a classic in the Disney animated canon and a definitive adaptation of Barrie’s work. Its enduring popularity stems from its ability to tap into the universal longing for childhood innocence and adventure.

Setting the Stage: London and the Darling Nursery

The film opens with the enchanting song “The Second Star to the Right,” accompanied by Mary Blair’s distinctive concept art, painting a vivid picture of Neverland even before the story truly begins. This opening sequence immediately establishes a sense of wonder and nostalgia, drawing viewers into a world of fantasy.

We are then transported to London and the Darling household. The narrator’s voiceover beautifully contrasts the adult perception of Peter Pan with the children’s unwavering belief. Mr. Darling, voiced with comedic exasperation by Hans Conried, embodies practicality and dismisses Peter Pan as “fantastical nonsense.” His wife, Mary, voiced by Jennifer Angel, views Peter Pan as a charming fable, a symbol of youth, but still firmly within the realm of imagination.

In the nursery, Wendy, John, and Michael Darling are fully immersed in the world of Peter Pan. Wendy, voiced by Kathryn Beaumont (who also voiced Alice in Alice in Wonderland), acts as storyteller, recounting Peter’s adventures to her younger brothers, John and Michael. Their playful reenactments and Nana, the St. Bernard nanny, create a warm and whimsical domestic scene, sharply contrasted by Mr. Darling’s insistence on order and adulthood.

Mr. Darling’s frustration with the children’s “Peter Pan nonsense” culminates in his decree that Wendy must grow up and leave the nursery, a decision that deeply upsets the children. This moment introduces a central conflict: the inevitable transition from childhood to adulthood, a theme that resonates throughout the film. The comedic chaos of Mr. Darling’s attempts to regain his cuff links and shirt, intertwined with Nana’s protective interventions, provides lighthearted humor while underscoring his disconnect from the children’s imaginative world. His decision to banish Nana from the nursery further escalates the tension and creates a poignant moment of family disruption.

Mary soothes the children, assuring them of their father’s love, while Wendy clings to the hope of Peter Pan’s arrival, even leaving the window unlocked. She reveals to her mother that Peter Pan had visited and Nana had captured his shadow, a detail that foreshadows the magical events to come. Outside, Mary expresses her concerns, but George dismisses them, oblivious to the magic about to enter their lives.

The Arrival of Peter Pan and the Flight to Neverland

Peter Pan’s entrance into the nursery is masterfully crafted, beginning with the ethereal notes of his flute and his shadowy, almost mysterious presence. Voiced by Bobby Driscoll, Peter is portrayed as a figure of youthful energy and slight mischievousness. Driscoll’s performance is notable as he was the first male actor to voice Peter Pan in a film adaptation, breaking from the tradition of casting women in the role for stage productions. His voice and character design capture a Peter on the cusp of adolescence, adding a layer of complexity to his eternal youth.

Accompanied by Tinker Bell, depicted here with a distinct form inspired by Margaret Kerry, Peter is searching for his lost shadow. Disney’s Tinker Bell, while visually distinct from the stage tradition of a light, retains her fiery personality and jealousy, traits that become central to the plot. Her communication through chimes, understandable only to Peter, adds to her whimsical and somewhat enigmatic nature.

The chaotic chase for Peter’s shadow awakens Wendy, who is immediately starstruck by the presence of the boy from her stories. Her non-stop chatter about Peter and his shadow contrasts with Peter’s initial bewilderment, culminating in his humorous exclamation, “Girls talk too much!” Wendy’s offer to sew his shadow back on serves as their first real interaction, establishing her nurturing nature and initiating their connection.

Wendy learns that Peter visits her window to hear her stories, which he then shares with the Lost Boys and mermaids in Neverland. She sadly reveals that her storytelling days are coming to an end as she is being forced to grow up. Peter’s horrified reaction to the concept of growing up and his immediate invitation for Wendy to join him in Neverland sets the stage for their adventure. His ignorance of mothers and Wendy’s explanation of maternal care leads to Peter’s impulsive suggestion that Wendy become the Lost Boys’ mother, a proposition that appeals to Wendy’s nurturing instincts.

Tinker Bell’s jealous outburst interrupts a tender moment between Wendy and Peter, highlighting her possessive nature. John and Michael awaken, adding to the excitement and wonder of Peter’s visit. Wendy’s question about her brothers joining them reveals Peter’s initial reluctance, suggesting a hint of selfishness in his desire for Wendy’s exclusive company. He eventually agrees, but only after securing their obedience, a moment that underscores Peter’s leadership and slightly autocratic tendencies.

The iconic “You Can Fly” sequence follows, explaining the whimsical mechanics of flight in Neverland: happy thoughts and pixie dust. The children’s flight around the nursery and out into the London night, set to the soaring music and chorus, is a cinematic highlight. Their journey past Big Ben and towards the “second star to the right” is a visually stunning and emotionally resonant sequence, capturing the exhilaration of flight and the boundless possibilities of childhood imagination. Nana’s frustrated barks as she is left behind and the near-miss attempt to bring her along with pixie dust add a touch of humor and pathos to their departure. The abandoned idea of Nana accompanying the children to Neverland and narrating the story from her perspective offers an intriguing alternative narrative path that remains unexplored in adaptations.

Neverland and its Inhabitants: Pirates, Lost Boys, and Mermaids

In Neverland, Captain Hook and his pirate crew are introduced, providing the central antagonistic force. Hook, voiced by Hans Conried (who also voices Mr. Darling), is a flamboyant and menacing villain, obsessed with Peter Pan. The casting of Conried to voice both Mr. Darling and Captain Hook subtly reinforces the thematic link between adult authority and the children’s antagonists. Hook’s first mate, Mr. Smee, voiced by Bill Thompson, provides comic relief with his bumbling nature and unwavering loyalty to Hook. Thompson’s voice work, also notable for characters like the White Rabbit and Droopy Dog, imbues Smee with a lovable ineptitude that contrasts sharply with Hook’s villainy.

Hook’s obsession with Peter Pan is evident in his relentless pursuit of the boy who cut off his hand and fed it to a crocodile. The ticking crocodile, a constant source of anxiety for Hook, adds a humorous and suspenseful element to his character. The cut song “Never Smile at a Crocodile,” repurposed as the crocodile’s theme music, further enhances this comedic tension.

The pirate crew’s restlessness and Hook’s single-minded focus on Peter Pan are highlighted in the scene where Smee attempts to shave Hook. Their banter and the slapstick humor, including the seagull shaving incident, showcase the comedic aspects of the pirate villains. Hook’s realization that Tiger Lily, the Indian Chief’s daughter, might know Peter Pan’s hideout sets the plot in motion for the next series of events.

The children’s arrival in Neverland is met with pirate cannon fire, immediately plunging them into danger. Peter’s selfless act of distracting the pirates while sending Tinker Bell to guide the children to the Lost Boys demonstrates a rare moment of altruism. However, Tinker Bell, driven by jealousy, manipulates the Lost Boys into attacking Wendy, mistaking her for a “Wendy bird.” The Lost Boys, differentiated primarily by their animal-themed outfits, are depicted as mischievous and easily misled. Their attempt to shoot down Wendy and her near-fatal fall highlight the dangers of Neverland and the consequences of Tinker Bell’s jealousy. Peter’s reprimand of the Lost Boys and his subsequent banishment of Tinker Bell (later commuted to a week at Wendy’s urging) further develop the characters’ dynamics and introduce themes of forgiveness and consequence.

Encounters and Controversies: Mermaids and “Indians”

Peter escorts Wendy to Mermaid Lagoon, while John and Michael join the Lost Boys on an “Indian hunt,” leading to the film’s most controversial aspect: the portrayal of Native Americans. The mermaids, initially enchanting, reveal a catty and unwelcoming side when Wendy arrives. Their attempts to pull Wendy into the water and their teasing about her nightdress expose a less idyllic aspect of Neverland’s inhabitants. Peter’s amusement at their behavior and his eventual intervention when Wendy retaliates with a shell further complicate his character, suggesting a detachment from social norms and a tendency towards playful chaos.

The “Following the Leader” song accompanies the Lost Boys and Darling brothers on their ill-fated Indian hunt. This catchy tune masks the problematic depiction of Native Americans that follows. John’s attempts to apply military strategy to “Indian hunting” are immediately undermined when the group is captured by the Indians, highlighting the children’s naivete and the limitations of their understanding of the world.

The portrayal of Native Americans in Disney’s Peter Pan is a significant point of criticism. The film relies heavily on outdated and stereotypical depictions, reflecting the prevalent prejudices of the 1950s. The “Indians” are characterized by exaggerated physical features, simplistic language, and cultural practices presented as caricatures. The song “What Made the Red Man Red” is particularly offensive, perpetuating racist tropes and trivializing Native American culture.

While the film’s creators have acknowledged the problematic nature of these depictions in retrospect, and Disney has largely avoided promoting these aspects in modern re-releases, the presence of these stereotypes remains a significant flaw. Comparing the depiction to Disney’s later, more consciously “PC” portrayal of Native Americans in Pocahontas reveals a stark contrast. While Pocahontas aimed for greater accuracy and sensitivity, it arguably sacrificed character depth and emotional complexity in its pursuit of respectful representation. The “Indians” in Peter Pan, despite being deeply stereotypical, are animated with more dynamism and emotion, ironically making them, in some ways, more “alive” as characters, albeit within a framework of harmful stereotypes.

The Chief, voiced by Candy Candido, is a formidable presence with his deep, gravelly voice, but his character is still rooted in stereotypical representations. The kidnapping of the Lost Boys and Darling brothers by the Indians, initially presented as a game, quickly turns serious with Tiger Lily’s disappearance and the Chief’s threats.

Rescue and Jealousy: Skull Rock and Tinker Bell’s Betrayal

Meanwhile, Peter and Wendy’s excursion to Mermaid Lagoon is interrupted by the ominous arrival of Captain Hook at Skull Rock, accompanied by a captured Tiger Lily. Hook’s ultimatum to Tiger Lily – reveal Peter Pan’s hideout or be left to drown – sets the stage for Peter’s daring rescue.

Peter’s impersonation of a “spirit voice” and later Captain Hook himself to trick Smee and rescue Tiger Lily is a showcase of his cleverness and playful nature. The comedic confusion between the real Hook and Peter’s impersonation, with Smee caught in the middle, provides classic Disney slapstick. Peter’s duel with Hook, observed by Wendy and cheered on by Smee, highlights his bravery and showmanship. The Wile E. Coyote-esque cliffhanger and Hook’s near-miss with the crocodile lead to another iconic comedic sequence of Hook desperately fleeing the ticking predator.

Peter’s triumphant crow after rescuing Tiger Lily is quickly tempered by Wendy’s reminder of their initial purpose. His somewhat dismissive “Oh yeah, what’s-her-face” underscores his self-centeredness even in acts of heroism. The scene transitions to Hook nursing a cold back on his ship, interrupted by Smee’s clumsy attempts to hang a “Do Not Disturb” sign. Smee’s innocent gossip about Tinker Bell’s banishment and Wendy’s arrival sparks Hook’s manipulative plan to use Tinker Bell’s jealousy to his advantage.

Hook’s calculated manipulation of Tinker Bell is a key plot point. He exploits her jealousy and feelings of abandonment, painting Wendy as a replacement and himself as an understanding confidant. His theatrical performance, complete with harpsichord serenade and dramatic pronouncements, effectively preys on Tinker Bell’s emotional vulnerability. Tinker Bell, blinded by jealousy, agrees to betray Peter and reveals the location of his hideout, securing Hook’s promise not to harm Peter directly. Hook’s immediate betrayal of this promise, trapping Tinker Bell and setting his plan in motion, underscores his villainy and cunning.

The Decision to Grow Up and the Pirate Attack

Back at the Indian camp, Peter is celebrated as a hero and made an honorary chief. The joyous celebration, however, is marred by the continued presence of the song “What Made the Red Man Red.” Wendy, tasked with collecting firewood, observes Tiger Lily and Peter’s affectionate interaction, fueling her own jealousy and disillusionment with Neverland. This, combined with her brothers’ increasingly “native” behavior, pushes Wendy towards a decision to return home.

Wendy’s announcement to her brothers that it’s time to go home marks a turning point in the narrative. Her attempt to reason with Peter about the practicality of returning to London echoes her father’s earlier pronouncements about growing up, highlighting the cyclical nature of the themes of childhood and adulthood. Peter’s insistence on staying in Neverland and his inability to understand Wendy’s longing for home underscore the fundamental difference between their perspectives.

Wendy’s poignant song “Your Mother and Mine” serves as the emotional core of the film. This heartfelt ballad evokes the universal theme of maternal love and awakens a sense of longing for home in the Lost Boys and the Darling children. Even the pirates are momentarily moved, highlighting the song’s emotional power. Peter, however, remains unmoved, further emphasizing his emotional detachment and resistance to the idea of growing up.

The Lost Boys’ decision to return to London with Wendy and her brothers signifies their acceptance of the transition to adulthood and the allure of home. Wendy’s assurance that her parents will welcome them all underscores her nurturing nature and her growing maturity. The abandoned storyline of Peter’s tragic backstory, revealing his own experience of being replaced by his mother, would have added a layer of depth and tragedy to his character and his resistance to Wendy’s departure. Instead, his dismissive “They’ll be back” reveals a degree of denial and perhaps a deeper loneliness beneath his bravado.

The children’s departure is abruptly interrupted by their capture by Hook and the pirates. Tinker Bell, having escaped, races back to warn Peter, arriving just as Hook’s bomb, disguised as a present, explodes. The massive explosion and its near-fatal consequences for Tinker Bell highlight the severity of Hook’s villainy and the stakes of the conflict.

The Final Battle and the Flight Home

Peter miraculously survives the explosion and finds Tinker Bell gravely injured. In a moment of genuine emotion, Peter expresses his deep affection for Tinker Bell, declaring, “You mean more to me than anything in this whole world!” This declaration of love and his refusal to leave her side marks a significant moment of character development for Peter, revealing a capacity for vulnerability and deep connection beyond his usual self-centeredness.

On the Jolly Roger, Wendy bravely refuses Hook’s final offer to join his crew, choosing to walk the plank rather than betray her principles. Her courageous farewell to her brothers and her tearful moment of private emotion showcase her strength and maturity. Just as Hook anticipates Wendy’s fall, Peter’s dramatic reappearance with Wendy on the masthead signals the beginning of the final battle.

The ensuing fight between Peter, the Lost Boys, and the pirates is a chaotic and comedic melee. Even Smee attempts a cowardly escape, adding to the humor. The sword fight between Peter and Hook is a cinematic highlight, showcasing dynamic animation, dramatic lighting, and rule-of-thirds composition that elevates the scene beyond typical animation standards.

Peter, disarming Hook and trapping him in the ship’s flag, offers him a humiliating but merciful defeat: declare himself a “codfish.” Hook’s forced declaration and the crocodile’s celebratory dance provide a satisfyingly comedic resolution to his villainy. Hook’s predictable betrayal and subsequent chase by the crocodile offer a non-fatal but fittingly comical end for the antagonist, deviating from the original story’s darker conclusion. This decision aligns with Disney’s evolving approach to villain fates, moving away from death and towards more karmic or humorous punishments.

With Hook defeated, Peter assumes command of the Jolly Roger, transforming it into a golden, pixie dust-powered vessel for the flight back to London. This magical transformation and the ship’s soaring flight through the night sky create a visually stunning and emotionally uplifting conclusion. This image of the flying pirate ship became so iconic that it was reused in the ending of the 2003 live-action Peter Pan film.

The transition from Neverland to London, shifting from the island to the moon, then Big Ben, and finally the Darling’s parlor clock, is a clever and seamless visual metaphor for the return to reality. The Darling parents’ return home and their discovery of Wendy asleep by the open window create a sense of closure and domestic warmth. Wendy’s recounting of her Neverland adventures to her bewildered father provides a final touch of whimsy.

The film concludes with a powerful and ambiguous moment. As Wendy sits by the window, observing Peter’s ship sailing through the sky, Mrs. Darling sees it too. She calls to Mr. Darling, who also witnesses the magical sight. Instead of fear or disbelief, George Darling is filled with wonder and a stirring sense of déjà vu, recognizing the ship from a distant memory of his own childhood. This ending, underscored by the swelling chorus of “You Can Fly,” leaves the audience with a lingering sense of magic and the enduring power of childhood imagination.

Enduring Legacy and Complexities of Disney’s Peter Pan

Disney’s Peter Pan (1953) is a complex and multifaceted film. While it deviates from some of the darker themes of J.M. Barrie’s original work, it successfully captures the spirit of adventure and the allure of eternal childhood. The film’s vibrant animation, memorable songs, and iconic characters have ensured its enduring popularity. Despite initial mixed critical reception, it has become a beloved classic and a cornerstone of Disney animation.

However, the film is not without its flaws, most notably the problematic and racist depiction of Native Americans. This aspect of the film requires critical engagement and acknowledgment of its harmful stereotypes, even while appreciating its other artistic merits.

Ultimately, Disney’s Peter Pan remains a powerful and resonant film because it taps into universal themes of childhood, growing up, and the enduring power of imagination. It is a film that can be enjoyed on multiple levels, offering both whimsical entertainment and opportunities for deeper reflection on the complexities of childhood and the transition to adulthood. Its legacy as a classic is secure, but its complexities and controversies deserve ongoing discussion and critical re-examination.